Ode to an Ash

“When great trees fall,

rocks on distant hills shudder

lions hunker down in tall grasses

and even elephants lumber after safety…”

—Maya Angelou

Ash trees are falling all over our farm—in the woods, on the driveway, by our front door. We shudder, and we lumber after our safety. We walk under these trees, ride horses by them, mow the lawn around their trunks. Dogs doze underneath. I have sat on my porch and watched limbs crash to the ground, grateful I was not planting bulbs in the soil below. I consider hunkering down—avoiding the woods altogether—but that’s impossible; the woods are my solace. Still, when I do walk there, I look up more than usual. Saddest, perhaps, is the ash by our front door, 50 feet high and three in diameter, with a crown like a martini glass. That tree was here long before we were—when we looked at the property in 1988, brought our son home from the hospital in 1990 and our daughter in 1994—standing sentry over our lives, on happy occasions and sad. Thinking of this tree reminded me of a children’s book, “The Giving Tree,” by Shel Silverstein, about a little boy in love with a tree—and the tree loves him so much that she gives him her branches to make a house, and her trunk to make a boat. “Once there was a tree… and she loved a little boy… And the boy loved the tree, and the tree was happy…”

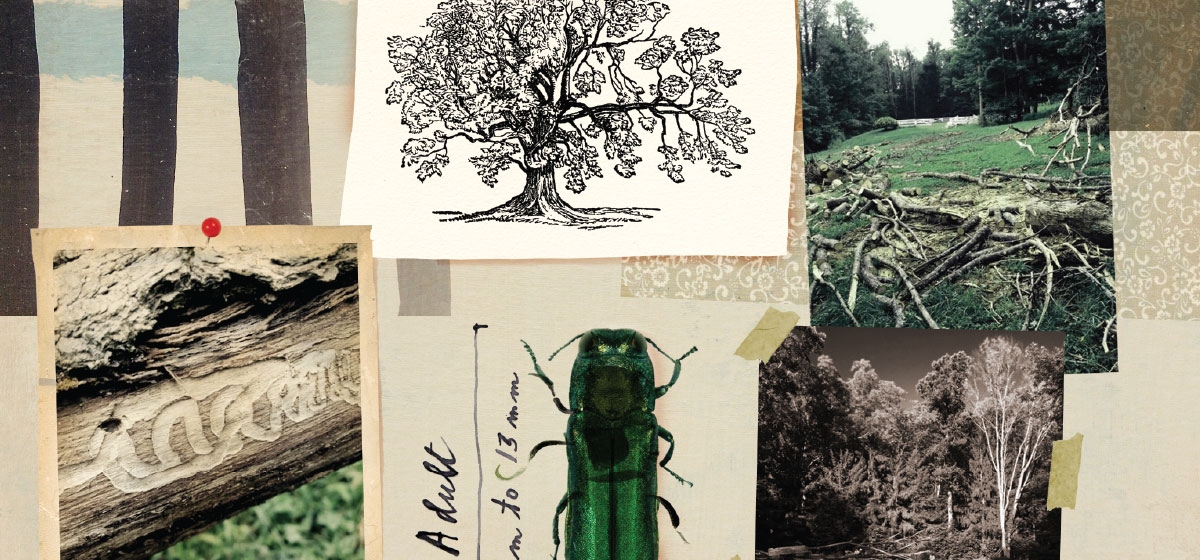

Ash trees aren’t just dying in Pennsylvania; they’re dying all over the Northeast—and beyond. “Texas just got on board,” said Brian Crooks, community forester of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. A month later, Nebraska was hit, then Delaware, and most recently Alabama was the 31th state to have the emerald ash borer. This half-inch long, shiny green beetle arrived from Asia in wood packing material, probably in cargo ships, but perhaps by airplane, and was first detected in Detroit in 2002, before which the beetle had never been seen in North America. But Deborah McCullough, a Michigan State professor of forest entomology, said a treering study subsequently revealed the beetle had been in Michigan at least 10 years earlier. It attacks predominately ash trees, of which there are 305 million in Pennsylvania; we have five native species, the most common being green, white and black. McCullough said green and black are the “preferred host. They get clobbered.” But in the field in western Pennsylvania, Crooks sees the destruction mostly of white ash.

This crafty little beetle spread across state lines by hitching a ride in timber, firewood, and nursery trees—and within a few years an infestation was born. (There is now a quarantine for moving ash across most state borders in affected states.) The beetle was first seen in Pennsylvania in Cranberry Township in 2007 and detected in Westmoreland County in 2009. Now nearly all the ash trees at our farm look like ghostly skeletons against an otherwise green background.

The top third of our sentry ash began to die back first, as is the norm. Adult beetles fed on its leaves in springtime, causing no damage, but then the females laid eggs, which hatched, and the larvae burrowed inside the tree, forming s-shaped tunnels, where they fed on the inner bark. That’s where the damage occurs, cutting off the tree’s food and water. “Basically the tree starves to death,” McCullough said. The following spring, adult beetles reemerged, and the cycle began again.

The beetles are difficult to see in the wild. I have tried but seen none. However, I have seen the beetle’s 1/8-inch, D-shaped exit holes in the tree’s bark, as well as holes left by woodpeckers, which prey on the ash borer larvae. I’ve also seen what’s called “bark flaking,” and, after the bark falls off, those s-shaped tunnels underneath.

Crooks said he sees devastation everywhere in Pennsylvania— in the city, on the turnpike, and in suburban yards, where the ash has been a popular tree with landowners “because of its big-tunnel shade effect.” And as any baseball fan knows, losing white ash trees is bad for the industry, which has traditionally used the wood to manufacture bats. McCullough called the emerald ash borer “the most destructive and costly forest insect to invade North America.”

“…losing so many large, mature trees is crushing. And it is sobering to think that neither my husband nor I will be around to see ash trees this size again.”

For me—and especially for my husband, who has spent nearly 30 years planting, pruning, and preserving trees—losing so many large, mature trees is crushing. And it is sobering to think that neither he nor I will be around to see ash trees this size again. We have begun to cut ours down—starting with the trees that pose a danger around the house, about 20 so far—and that’s only the beginning.

Felling trees is costly and causes a colossal mess. Chemical treatments exist, which involve drilling into the trunk and injecting insecticide, which McCullough said has improved since 2002, but trees must be treated before they are severely injured. “If half the canopy is alive, it’s worth using.”

Crooks suggested contacting a board certified arborist to decide what to do with dying ash trees. “Anyone can walk out there with a bucket truck and say they’re an arborist, but they’re not going to give advice about how to replace trees.” When replacing the ash, he advised planting different varieties. “Diversity is your friend,” he said, suggesting swamp white oak, American sycamore, London planetree, hackberry, and disease resistant elm cultivars like ‘Accolade’, ‘Emerald Sunshine’ and ‘Morton Glossy,’ to name a few.

In his book, The Hidden Life of Trees, German forester Peter Wohlleben writes that trees transmit electrical signals between themselves to share news about insects, drought, and other dangers via fungal networks at their root tips, “like fiberoptic Internet cables.” The journal Nature calls this “the wood wide web.” Early research indicates that trees may communicate also by sound waves, and, according to Wohlleben, beeches, spruce, and oak “register pain when a creature starts nibbling on them.” Reading this made losing our ash trees that much worse.

But then I thought again of The Giving Tree. When the little boy grows into an old man, the tree says she has nothing left to give. “I am just an old stump.”

“I don’t need much now,” said the boy, “just a quiet place to sit and rest. I am very tired.”

“Well, said the tree, an old stump is good for sitting and resting. Come, Boy, sit down and rest. And the boy did. And the tree was happy.”

Stumps are all we will have left of the many ash trees on our farm. And so we will sit, and rest, and hope that—somehow—the tree is happy.