My Oldest Brother

Just before 6 a.m. on New Year’s Eve, I got in the car to drive down to Cincinnati, my hometown. I’ve done it 100 times at least since I moved to Pittsburgh 39 years ago. And I’ve done it for all manner of occasions. This time, it was to see my oldest brother. His heart had stopped the day before, and doctors had revived him.

As I sped through the pre-dawn darkness, I considered his situation. As different as we were, we had the family heart disease gene in common. We’d both researched it and discussed it for years. And for years, Ken had stiff-armed Death. He’d kept it at bay by being a disciplined, competitive swimmer. Even so, he’d had a previous heart attack, a quadruple bypass in 2001 and, in 2008, he collapsed after a swim meet in Louisville. It took six paddle shocks to restart his heart.

Our father, grandfather and great-grandfather all died at 73, and we all cheered when Ken defied that barrier. Now, however, five months shy of his 80th birthday, he was living on borrowed time, and we all knew it, especially given how weak his heart had become. The day before, my sister Nancy, the second oldest of us five kids, had filled me in. Ken was weak and needed rest. I had to be back in Pittsburgh by 5 p.m. anyway, so I wouldn’t stay long. But this would likely be the last time I’d see him. And as Cincinnati neared, I rehearsed the three things I wanted to say.

Kelly, the younger of Ken’s two daughters, was in the hospital room when I arrived. My nieces are much closer in age to me than my brother is, and we gave each other a hug. Ken was much thinner than I expected. He’d always been a thin, six-footer, smaller boned than I — taking after our mother more. But this was different. I told him he looked like an Eichelberger, our mother’s family, which I knew he’d like. And as we talked, I pulled my chair a little closer so I could hear better. He was indeed weak, but in good spirits, and we swapped stories and happy memories about Mom and Dad.

When father and one-year-old son met for the first time, the newspaper’s caption quote was: “I’m not very good at handling babies.”

At some point, Kelly was understandably giving her father a pep talk about how he’d leave the hospital soon. For better or worse, that was my cue to mention the first thing I wanted to tell him. I said he might well get out soon, but for all of us, at some point, our time would be at hand and that if his were near, with the life he’d lived, he had nothing to worry about. And I mentioned a little speech Socrates once gave that it didn’t make sense to fear death, that for all we know, it might be the most wonderful blessing.

As I said that, I remembered something Ken said occasionally over the 30 years since our parents have been gone. When I’d done something noteworthy or had good news, Ken would say in a cheery voice, “Hey, that’s great! Mom and Dad are up in the balcony cheering!” It was a nice thought, and I knew that, perhaps for different reasons, both he and I felt that somehow that was true, that our parents were still somehow looking over us, “in the balcony.” I didn’t mention the balcony that day; I could feel the emotion starting to well up.

I’d been there for 40 minutes, and it was time to let him rest, time to say the last two things. I told him he’d done a great job carrying the family banner after Dad had died and being the family leader in Cincinnati. I knew it would mean a lot to him, and it did. And then I thanked him for being such a good older brother to me. And we shook hands and smiled, both with tears in our eyes, and I left.

***

When I meet someone and we talk about our families, I often say, “I’m the youngest of five. My oldest brother was 18 when I was born and drove my mother to the hospital because Dad was out of town.” It generally gets a laugh and, often, a question: Did you have the same parents?

The short answer is yes. However, the truth is that our parents were entirely different, and the families and world we came into barely resembled each other.

Christened Kenneth Heuck Jr., my brother was born in June of 1944, when his namesake — our father — was a battled-tested 24-year-old naval officer on a U.S. destroyer in the Pacific. Dad had requested shore leave for the birth, but his skipper replied: “You may have been responsible for the laying of the keel, but you’re not necessary for the launching of the ship.” Dad’s ship, the U.S.S. Luce, was steaming toward the biggest naval battle in history at Leyte Gulf, the Philippines.

The writer’s brother rides on the shoulders of their father, just back from the Pacific in 1945.

Ken was very nearly my parents’ only child. When he was 11 months old, a kamikaze scored a direct hit on Dad’s destroyer, which blew up and sank off of Okinawa. Forty percent of the men died in the shark-infested waters and for days on end, no news reached Cincinnati as to whether Dad, a college swimmer, had survived.

Ken was a year old when Dad made it home and saw him for the first time. The reunion made the front pages of the Cincinnati papers. He was the first grandchild of both families and my paternal grandfather celebrated his birth by painting a bright, beautiful, and happy self-portrait with a big bottle of Old Grand-Dad in the foreground.

The Baby Boom was just beginning and two years later, in 1946, my parents had their first daughter, Wendy. But for that little family, the happy post-war years were cut short. At just less than a year old, Wendy died of SIDS when my parents were out for the evening and had a sitter. Our mother fell into a deep depression, which she later told me lasted 10 years. There were no drugs then, and her doctor warned her against having more children, saying she wasn’t up to it. She rejected that advice, telling me years later, “I had to have another baby, to survive.” And so, in 1948, my sister Nancy was born. Dad, working full time, did the best he could to hold things together.

There’s another clipping from the Cincinnati Enquirer with little 3-year-old “Kenny” sitting on the lap of a smiling, uniformed police officer in a city precinct. It’s a funny little feel-good story about how this little boy took a walk and ended up at the police station, saying he was going to visit his aunt. When I first saw that yellowed clipping as a kid and asked Mom about it, I could tell she didn’t like it, but at that age, I didn’t know why. The real story wasn’t funny. Back then, she’d been somewhat out of it and Ken left the apartment unnoticed and walked down the sidewalk of a busy avenue alone. A black woman saw him, picked him up in her car and dropped him off outside the police station. Not wanting trouble with the law, she told him to go inside the station and waited until he did.

Ken was born into a world of uncertainty, to young parents engulfed by war and loss, who struggled for solid footing.

The world I entered in 1962 was almost an exact opposite. My parents were confident, experienced, and happy. They were in their early 40s, with four children, all born four years apart in Presidential election years. And when I came along six years later, an unexpected surprise, I was born into the loving protection of a large family, secure in every way.

My parents had moved to an idyllic, suburban village, to a house with “the biggest yard in town.” It had an apple orchard, a cider press, enough room for football and baseball games, and a white picket fence all around it. We lived at the corner of Mariemont (pronounced Merry-mont) Avenue and Pleasant Street. Across the street was a beautiful, 20-acre park where a carillon in a majestic bell tower chimed on the hour and played concerts on weekends. It was an insulated bastion of white Protestantism, with a town square — a place where children walked to excellent public schools, and when we played in the neighborhood, the smell of baked cookies was everywhere, wafting in from the cookie factory in the next town.

***

Among other things, birth order theory says the oldest and the youngest have the luckiest spots in the family. Parents pour attention and expectation onto the oldest, who by default becomes the leader. When the baby comes along, the parents are experienced and more relaxed, making a happier, free-spirited child.

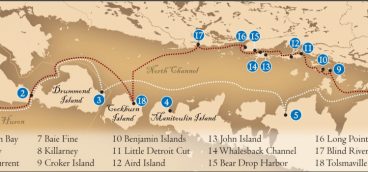

The expectations certainly were piled onto Ken. During his childhood, the family name was well-known in Cincinnati. Our great-grandfather, a German immigrant, had opened a string of vaudeville theaters with headliners such as Buffalo Bill and Harry Houdini. He fought and prevailed against the city’s blue laws, which sought to keep unruly immigrants in line. Our grandfather had been elected Hamilton County Auditor and Recorder and helped lead a reform that threw out the political boss. He held the University of Cincinnati Bearcats touchdown record for almost 50 years and was a sought-after public speaker and raconteur. Dad was a businessman, a combination family man/intrepid go-getter who, with Mom, raised a family of five, loved his farm and skippering long and sometimes dangerous sailing races on Lake Huron.

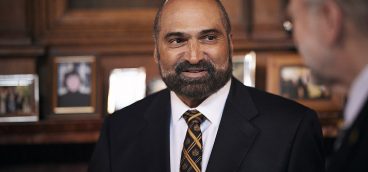

Ken grew up in the thick of all of that, working on the farm and crewing with Dad on races where the waves once hit 20 feet. He revered Dad, who was his best friend, and Ken was a dutiful son. By the time I came along, Ken was a tall, good-looking college guy, who became Senior Class President at U.C., where the family legacy was still strong. He then became a lawyer. Somehow it was seen as a good idea for Ken to carry on the political tradition, so he ran for City Council, and the whole family helped. I organized gangs of middle school friends to leaflet neighborhoods and hold signs at Bengals games. Though he didn’t win, he made a good showing — and the political wisdom said no one won the first time and that he was a shoo-in to win on his second try.

But it wasn’t for him. He just wasn’t suited for that. By nature, he was more like our mother, quiet and gentle. But because of the City Council run, he was appointed to the state Workers Comp Board as a Republican. But Ken confounded the Republicans by being sympathetic to the workers getting injured. And so began his 53-year career as a personal injury lawyer, helping the underdog find redress in the justice system.

***

When I was in high school, I had an “internship” with Ken, which amounted to my looking up cases in dusty old law books in a dimly lit office tucked into an obscure building somewhere Downtown. It was nice of Ken to do that, but it wasn’t for me.

My brother and I were different in many ways.. He was quiet. I was outgoing. He was the first. I was the last. And so on. Over the years, some have been hard-pressed to see similarities. But they existed. Despite our differences, we saw some fundamental family things the same way. It was unspoken, but we both knew it, and I believe we felt it more than the others. Though it may seem antiquated or quaint in this day and age, we both acutely perceived the importance and need to carry on the traditionally male role of family leadership, the responsibility to carry the family banner and further the family name. Maybe it’s a fool’s errand to write your name in the sands of time, but we saw it as our destiny to try. And it was important to do that in our hometown — in Cincinnati.

Though Ken was the oldest, leadership, as traditionally defined, came more easily to me. It always has, and from his perch 18 years ahead, Ken always cheered me on and celebrated what successes I had.

When I was in high school, I knew a lot of people across Cincinnati. I always figured I’d move back one day and maybe become a civic leader like our grandfather. In 1990, after Dad’s stroke, that time was at hand, and I started the process of moving our young family there. I’d become a “bigshot” reporter and figured I could easily get a job there. We’d have Mom and Dad, who was in a wheelchair after the stroke, move in with us, and we’d start new lives there.

But the Cincinnati papers, which weren’t as good as the Pittsburgh papers, wouldn’t hire me. I even checked with my second cousin to see if he needed help running his kitchen gadget company. He didn’t but was nice enough to show me the plant. I was trying whatever I could at the age of 28 to get back home, take care of Dad, and take on the role he would soon be leaving. But as the doors kept closing, I realized that what I thought my life would be — taking my place in the line of the family in our hometown — was not to be. And so I stayed in Pittsburgh, my wife’s hometown, feeling it was important to raise our children where one of the two families were. And I rearranged my view of the future.

I thought about all that as we drove down to Cincinnati again on January 25. Ken had passed away five days earlier, two days before my 62nd birthday. And I thought about the role Ken had played. He was the elder of his own family, married for 53 years and grandfather to six vibrant grandchildren.

When I thought of Ken‘s contribution, I thought most of our nephew Jon, who has had special needs since his premature birth. When he was a boy, maybe 40 years ago, we had a great time together. I’d carry him into boats and we’d drive around, Jon at the wheel. From his boyhood on, Dad was his close buddy, advising him on all manner of things. And after Dad ended up in a wheelchair too, their special bond grew. When Dad died, no one felt it more than Jon.

Into that void stepped Ken, and for the last 30 years, he and Jon have been close pals in a world that isn’t easy for Jon. When Jon called, Ken was there, and they talked about all manner of things, often sports.

What is leadership, I asked myself as I drove? Is it furthering the family name? Is it being social and hosting big family parties? Those were two things I thought when I was young. Is it being well-known and being a big shot? Or is it helping others and doing the little things? And maybe the little things really are the big things?

***

I remembered one time, Ken, our brother Bob and I were looking for a Christmas tree on Christmas Eve, as was the German tradition. I was probably 20. By the time we got there, the tree place was closed, but there were plenty of trees. I looked at Bob and said, “Well, they’re not going to be worth much tomorrow. Let’s get one.” Ken objected and when it was clear that we were going to get one anyway, he walked away, distancing himself from the act. I understood why he did it, being a lawyer, but I took the tree and left some money at the stand.

As I drove, the phrase “following the straight and narrow” came to mind. I mulled it and wondered where it came from. Was it a criticism to say that Ken lived on the straight and narrow? It seems to have a pejorative meaning now, almost an implicit criticism of someone as boring. But I vaguely recalled its meaning something else. So I looked it up. It’s from Matthew in the Bible: “Wide and broad are the ways of life that lead to falling by the wayside. But straight and narrow is the path to heaven — and few it is, who are able to follow it.”

In a world full of loudness and lewdness — if you’ve got it, flaunt it — how unusual it is to have someone still follow the old ways of humility, stoic fortitude and sacrifice for the good of others — where such sacrifice is simply who you are and what it means to be your father’s son, just as it has been for generations stretching back far beyond memory. That was Ken.

***

My brother’s family decided to have a small family service and not to have the funeral in the church. We three younger siblings fretted about that like a Greek chorus. A church funeral was traditional. People knew Ken and would expect it. And so on. But the service to follow was better than anything I could have imagined.

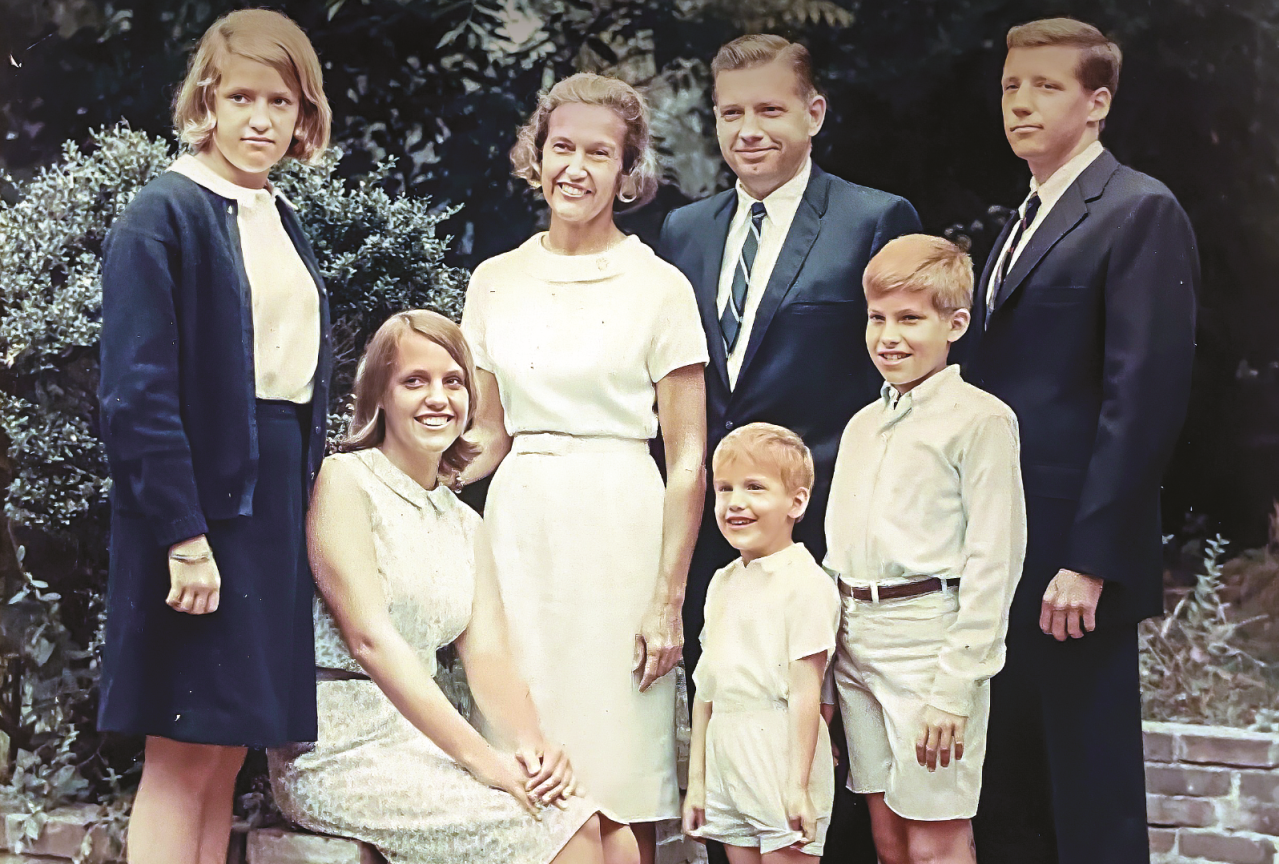

This is the last photo of all five siblings, at a 2015 wedding. From left: Susan, Nancy, Doug, Bob and Ken.

My wife and I arrived early to Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery, the beautiful 180-year-old arboretum. Though it was late January, it was a mild day, and we drove around looking at names and magnificent monuments, before pulling up to where the family were arriving. We said hello to everyone before the procession began its winding route to the gravesite.

My sister Nancy, always the closest to Ken and now the oldest of our siblings, gave the best, most profound and beautiful eulogy I have ever heard (and I’m a fan of speeches). A cousin by marriage did a very nice job helping. And then my nephew (one of Nancy’s sons) played “Amazing Grace” on his tenor sax and his oldest brother passed out pens and little strips of birch bark that came from our place in northern Michigan. Nancy asked us to write on the birch bark one or two words that came to mind about Ken, and then we each went around saying what they were.

Then we climbed the little hill to the grave. Some of us, including me, were pallbearers. Ken would have loved being carried by his brothers but especially by his five grandsons, all strong, handsome young athletes.

We carried him to the spot right next to our parents, just below the stone bench bearing our family name. The able young cemetery attendants lowered the casket, and then, we all dropped our different colored roses into the grave, as well as our pieces of birch bark.

I kept my white rose because, in many ways, Ken was a pure person. And then after a prayer probably, which I don’t recall, we all began to slowly migrate across that hillside, maybe 20 yards away to where our grandparents, aunts, uncles, great-grandparents and Wendy were buried. And there, on that hillside in Cincinnati, Ken, having done his part, will rest in the bosom of the family.