My Eureka Moment

So there I was in early 2015, six months after my heart attack and open heart surgery, taking 12 meds and being urged to add another two to the regime. Instead of rebelling, I was Mr. Goodpatient, passively doing whatever I was told, however insane it seemed.

When you’ve had a heart attack, one of the things your docs will insist on is that you have frequent stress tests. These annoying checkups require you to get yourself shot up with a radioactive isotope, wait 40 minutes, get a resting echocardiography, then exercise yourself to death, then get a stress echocardiography. This procedure was, I believe, invented by Dr. Frankenstein.

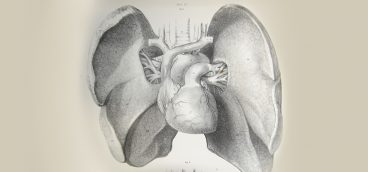

The main thing the docs are looking for in heart patients is blocked arteries, which show up as “cold” spots on the images. But the tests also measure something important called the “ejection fraction” (EF).

When the heart muscle is at rest, the ventricles fill up with blood. Then, when the heart muscle contracts, some fraction of that blood is pumped out to the body. Ideally, enough blood will get pumped out to do all the work the heart is supposed to do, but not so much that the ventricles can’t fill up again in-between heart beats. A healthy heart will have an EF between 50% and 65%.

When I had my last pre-heart attack stress test, in 2013, my EF was 65% – virtually perfect. Six months after my heart attack and open heart surgery, my EF was 46%. No wonder I could barely get through the day.

The reason for a low EF can vary from patient to patient, but in my case there was no mystery about it. So much of my heart muscle had died during my heart attack that my heart was simply not strong enough to perform all the duties demanded of it by my body.

When heart muscle dies it turns into scar tissue. Not only does scar tissue not pump blood, but it acts as a lead weight on an already weakened heart. To add insult to injury, scar tissue also interferes with the electrical conductivity of the heart, so that you end up with all sorts of erratic heartbeats, further weakening the heart.

This condition is called “congestive heart failure” and it’s not something you want to get—it’s basically a death sentence. The problem is that once a heart becomes too weak to do its job, the demands of trying to do the job make the heart ever weaker. Everything goes downhill and as time goes by it goes downhill faster and faster.

Doctors measure the declining heart function by looking, among other things, at the ejection fraction. As noted above, my EF had declined radically following my heart attack, and the prognosis was grim. On average, a congestive heart patient’s EF will continue to decline by about 10% per year, accelerating once it gets to about 30%. At that point you are typically in hospice care.

The brain deals with congestive heart failure via triage. Less important bodily functions get cut off, or receive a much-reduced blood supply, so that more important parts—the brain, e.g.—can continue to be supplied. (The human brain weighs only a few ounces, but it uses a full 25% of all the energy needed to run the body.) The extremities—legs and arms—are usually the first to go, which is why advanced heart patients walk so slowly and uncertainly—if they can walk at all.

But as the heart continues to weaken, more and more important bodily functions get cut off from the blood they need. At the end, even the lungs get cut off and many heart patients effectively drown in their beds.

On that happy note, I’ll point out that I’m getting ahead of my story.

The day in January of 2015 when I walked into the clinic to do my stress test, I found the waiting room packed with people. Half these people, I learned, were there for their stress tests and half were accompanying them. Every single person in the room had a caregiver with them—a spouse, an adult child, a friend, a hired nurse. There was only one chair left and I took it.

The fellow next to me was only 46 years old, but he looked awful. His skin was pale and blotchy and he had that slightly vacant, slightly anxious look people get when they’ve experienced a traumatizing event. The guy told me that he had had his heart attack almost a year earlier and that he felt even worse now than he had felt after the attack.

The fellow went in to get shot up with radioactive liquids—his daughter helping him out of his chair and into the testing room—and then the daughter returned. I told her how sorry I was to see the condition her father was in and suggested, gently, that maybe a harsh treadmill experience possibly wasn’t the best idea in the world for him.

“Oh, Lord,” she said, “there’s no way Dad could do a stress test on a treadmill! He does what they call ‘intravenous pharmacological stimulation,’ ” which turned out to mean lying in a bed and having them shoot you up with something that makes your heart race.

“That poor guy,” I said. “He must have had a really bad heart attack.”

But the daughter told me his heart attack hadn’t really been that bad. He’d gotten by with stents, rather than the open heart surgery I’d endured, which leaves you feeling like you’ve been in a really, really bad traffic accident.

“To be honest,” the daughter said, looking around to be sure her father wasn’t in earshot, “I think it’s his medications more than his illness that are the problem.”

She went on to detail the usual over-medication nonsense that my father had gone through. And, like my Dad, her father had faith in his doctors and wouldn’t hear of skipping even one of the meds.

That was my eureka moment. Here was an otherwise healthy 46-year-old guy who had had a not-very-bad heart attack, and the meds he was on were literally killing him. He felt like hell, he couldn’t even think about exercising, and so he was on a rapid glide path to the hospice center.

Yet he and I were on almost exactly the same meds!

I (figuratively) slapped myself upside the head and vowed (again) not to be Mr. Goodpatient, but to take responsibility for my own health. Which is what I did—and with a vengeance—as we’ll see next Friday.