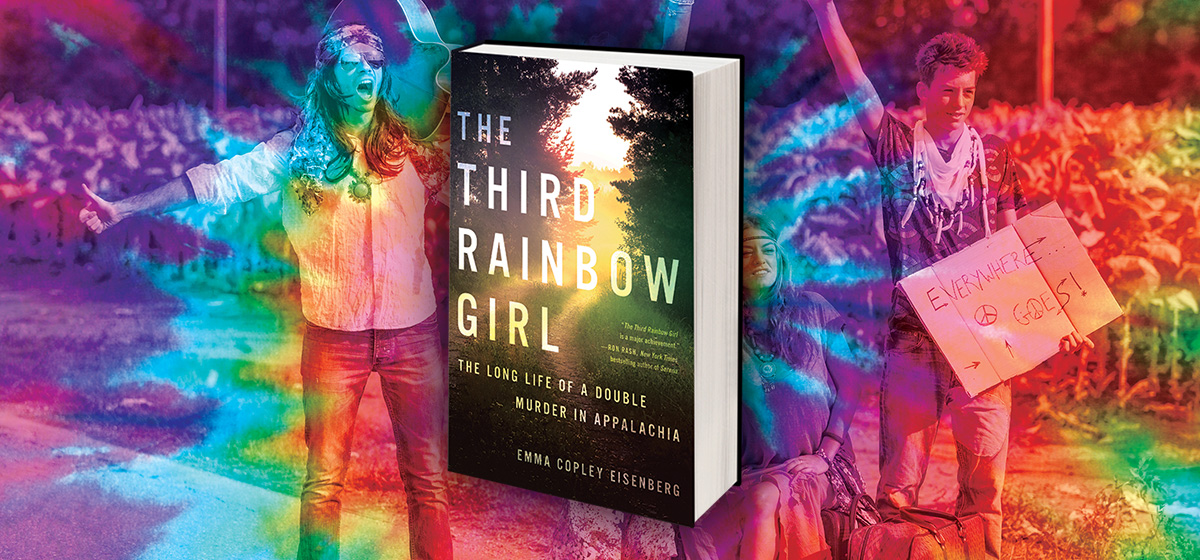

Murder, She Wrote

In 1980, three women hitchhiked to an outdoor peace festival in West Virginia called the Rainbow Gathering. Only one survived. Accusations and mystery swirled in the nearby town for decades.

This juicy setup is perhaps the most obvious reason to recommend Emma Copley Eisenberg’s first book of nonfiction, “The Third Rainbow Girl: The Long Life of a Double Murder in Appalachia.” For 13 years, no one was prosecuted for the Rainbow Murders. In 1993, a local farmer was convicted, then released when a schizophrenic man claimed responsibility. Eisenberg interviews the hitchhiker who survived in an attempt to piece together a fuller picture of those days and that era, but the mysteries only deepen. Her reporting is downright page-turning. It’s quite possible that the setup is the only sales pitch required for true crime fans.

But the murders comprise just a few blood-red pieces of the book’s larger, stained-glass structure. Eisenberg gracefully skips from the past to the present, from her own personal narrative to Appalachia’s cultural history. This book asks bigger questions than “who did it?” Eisenberg asks: Why do certain journalists and certain regions get wrapped up in certain stories?

Eisenberg is something of an expert on the culture of Appalachia. She has spent enough time in the region to possess an insider’s credentials, yet she still retains an outsider’s journalistic perspective (currently, she lives in Philadelphia). When it comes to familiarity with Pennsylvania and its adjacent roads, veteran truckers and individuals campaigning for state political offices might be the only two more well-traveled parties. Eisenberg would certainly be entitled to a told-you-so about the region’s simmering economic and cultural conflicts. She was publishing essays called “We Still Don’t Know How To Talk about Pennsatucky” back in 2015, right as national outlets were beginning to realize that Appalachian voters may play a disproportionate role in the upcoming election. But she is the type of relentlessly curious writer who would prefer to plunge deeper into the research than pause to gloat.

By her own account, Eisenberg had little to gloat about before becoming a writer. In her early twenties, she struggled to sync her beliefs with her actions. She recounts early in “The Third Rainbow Girl” how, by the end of her college years, she had “destroyed every God—religion, literature, politics, feminism, art—with my self-important words, dismissing each as problematic and essentially worthless.” She then found some personal breathing room while teaching young girls to become self-sufficient women at a wilderness camp in Pocahontas County, W.Va., where the Rainbow Murders took place 30 years earlier.

Eisenberg’s epiphanies at this camp are not limited to learning about the book’s titular crime. “Murder” is the buzziest word in the book’s title, but unpacking the words “Girl” and “Appalachia” are in many ways the driving force behind Eisenberg’s reporting and writing. Eisenberg encapsulates the nature of her work better than I can: “If every woman is a nonconsensual researcher looking into the word ‘misogyny,’ then my most painful and powerful work was done in Pocahontas County.”

The work is painful in part because Eisenberg’s female students who received good grades “by and large left” Pocahontas County. The ones who didn’t “mostly got married and had kids and lived in houses that sat far from [U.S. Route] 219, their lives already lived in private.” The result is a society where women are either absent or secluded.

In her recurring, big-picture overviews of Appalachia, Eisenberg smartly decides when to provide these kinds of generalized anecdotes from her years in the region and when to offer heartier statistical evidence. She is a large-hearted quoter of the region’s artists, scholars and thinkers, but she’s also a sharp critic of those who have misrepresented it. She performs a nifty bit of literary archaeology, detailing how, when more highly educated writers moved into the region in the 1880s, “their eyes flicked over the forested landscape and created a new genre: the local color novel,” focusing on the region’s “backwards, strange, and childlike people.”

She also tackles a challenging question: What is Appalachia? Or perhaps: where is it? And who is it? Eisenberg doesn’t subscribe to some grand unifying theory. She outlines key historical events and geographical idiosyncrasies. She creates a makeshift bluegrass syllabus that will make you want to pick at the nearest instrument, or at the very least, download a few songs. For Pittsburghers like myself who perhaps waste too much time debating to what extent Pittsburgh is northern or midwestern, Appalachian or part of the Rust Belt, “The Third Rainbow Girl” serves as a good reminder that a place is best encapsulated by considerate depictions of its rituals, land and people as opposed to its labels.

It’s worth stating a little more succinctly that Eisenberg can flat-out write. She regularly back-ends a long section of cultural analysis with a brilliant closing line: “No law is the best law seems to be the unspoken slogan of West Virginia.”

The book is full of these spot-on, convincing summations. It’s full of thorough reporting and laced with both history and first-hand cultural analysis. She’s the kind of writer you wish could live in a thousand places so she could explain every forgotten nook of the world.