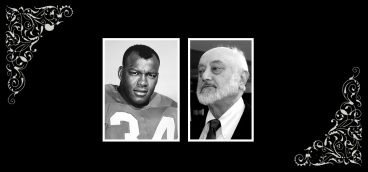

Art Collector G. David Thompson

What might be described as the great collections built up by Pittsburghers — those of, say, Henry Clay Frick, Gertrude and Leo Stein, Duncan Phillips, Andrew and Paul Mellon respectively, and Walter Arensberg — are perhaps best understood as being financed by Pittsburgh. The actual collections were built up elsewhere.

That is not true of the least famous of the great Pittsburgh collectors, G. David Thompson, who made most of his money here, from scratch, and whose collection was lodged here until his death in 1965. Had it been kept together and had it been housed here, as once was his wish, the arts world of Pittsburgh would have been a different place. But, as many collectors are, he was a difficult old cuss.

We traditionally think of collectors as cautious, scholarly types, moving with care, well-advised, with a few dealers and curators in tow. And superficially Thompson might have appeared thus, arriving in the gallery of a Swiss art dealer, with the director of the Carnegie Museum beside him. Minutes later, however, the dealer, Ernest Beyeler, reports Thompson stalking out red-faced, his offer for a Rodin, a Giacometti (and a few other works) being rebuffed. It was to be the beginning of a long and complex relationship, veering from trust to distrust, to accusations of duplicity, to temper tantrums and brinkmanship.

To understand Thompson is to explore a special psychology, unusual even for a collector.

Born in 1899, he was trained as an engineer at Carnegie Tech (having earlier abandoned a promising career as a singer) and became an investment banker in New York. In 1928 he purchased his first serious work of art, a Paul Klee. By 1945 he was the head of four steel companies.

His collecting and his business life proceeded simultaneously and with equal aggression: “A hard taskmaster and a tough negotiator” is how David Rockefeller described him. Beyeler added, “As a buyer he could be truly vicious.” It has also been said that he failed to be accepted by Pittsburgh’s social elite, yet another rebuff, and one from which he was not to recover. As John Richardson, the biographer of Picasso, suggested in his memoirs: “It was Dave’s aggressiveness and bragging, not his humble origins that made him persona non grata…To get back at the old guard, Dave set about trouncing them in the field of modern art — the one field where the old guard would not have noticed or cared whether they had been trounced or not.”

It is not strictly true to describe Thompson as solely a collector of modern art, for his interests were many and varied. He had a taste for folk art, Americana, Oriental porcelains and even Islamic art, and he collected them with an independent eye. In fact the quality of his “eye” has frequently been questioned, particularly by Richardson as “far from dependable.” More brutally, the collector-expert Douglas Cooper said to Thompson’s face, “You’ve got to stop being such a sucker. That Miro’s not a Miro!”

When Thompson’s collection was shown at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in the early 1960s, he, himself, wrote in the introduction to the catalog: “Taste and experience play an important role. During the early years I classified art as abstract or realistic, and by schools such as Dada or Surrealist. Today I recognize but two kinds … Good Art and Bad Art.”

His collecting practice was in direct opposition to that of the connoisseur. He liked to buy in bulk: “What isn’t selling, late Klees maybe? O.K., I’ll take the lot.” This is a practice not unknown in well-off major museums. The J. Paul Getty Museum’s collection of photography was almost built up overnight with a series of bulk purchases. It is also how fortunes are often built in the business world. Richard Armstrong, director of the Carnegie Museum of Art, draws particular attention to Thompson’s collection of 70 works by Alberto Giacometti, which Thompson sold in the early 1960s to the dealer Beyeler. That collection was divided between three Swiss museums: the Kunsthaus in Zurich and the Kunstmuseums in Basel and Winterthur. (The Carnegie has an iconic Giacometti, which ironically, did not come from Thompson.)

Shortly afterward, Beyeler purchased the greatest private collection of work by Paul Klee from Thompson, some 100 in all, for around 20 million Swiss francs (around $5 million at the time). This collection was sold entire to the city of Dusseldorf (the Rothschilds were also in the market for the collection).

The sale of these remarkable tranches of an even greater collection had been precipitated by two things. First, the death of Thompson’s son, David, in 1958, little spoken of at the time, must have had substantial influence. Two sculptures by Henry Moore (who may have been Thompson’s close friend) were given in his son’s memory to Harvard University and to the Carnegie Museum. The latter sculpture, Reclining Figure, 1957, stands in the forecourt of the Scaife Wing today. And second, was the rejection in 1959 of his offer to give or sell the collection (essentially, a deal) to the Carnegie, on condition that a freestanding building, bearing his name, would be constructed to house it. The story of the failure of this proposal, which could have entailed a cost of nearly $7 million, is variously recounted.

The A.W. Mellon Foundation would then have been the principal funder of such a venture, but was at that time financially preoccupied with the construction of the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Armstrong suggests that Thompson simply changed his demands to an unacceptable degree, which seems entirely in line with his practice. Whatever the real story may be, and we may never know it all, the remaining fact is that the collection has been conservatively estimated as being worth, by today’s escalating prices, perhaps some $350 million. The museum’s de Kooning, an outright Thompson gift that actually happened, is worth $20 million to $25 million.

The decision not to build a Thompson building clearly made Beyeler’s fortune, and ironically, it is Beyeler who has a museum containing his collection and bearing his name in Basel, Switzerland. Beyeler, in addition to “disposing” of the Giacomettis and the Klees, was to handle another 340 works of art from Thompson, exhibiting the collection variously in New York, Zurich, The Hague, Dusseldorf and Turin.

The collection was something of a chameleon, always changing as Thompson continued to barter and deal. At any stage it might have consisted of works by Picasso, Bonnard, Klee, Braque, Cezanne, Degas, Dubuffet, van Gogh, Kandinsky, Gorky, Held, Kline, Krasner, Leger, Matisse, Monet, Mondrian, Monet, Rauschenberg, Pollock, Vuillard and Wols. The names alone suggest an inconceivably rich assemblage, of an almost baroque character.

Thompson was also a generous donor. The Carnegie Museum of Art has what some regard as its greatest work of art, Willem de Kooning’s “Woman VI,” 1953, as well as the Henry Moore and some 80 other works of art given by Thompson over the years.

Allegheny County has the monumental mobile by Alexander Calder currently on display at the Pittsburgh International Airport. The Museum of Modern Art in New York (of which he was a trustee) received Picasso’s great masterpiece “Two Nudes,” 1906, in honor of Alfred Barr, the museum’s founding director and Thompson’s good friend.

A spectacular robbery in 1960, (masterminded by a disgruntled art historian, conjectures Richardson) deprived Thompson and his wife of some of their choicest masterpieces, including a Picasso, from their South Hills home. The paintings were ripped from their stretchers and seriously damaged, but were later recovered after a cloak-and-dagger exercise involving the FBI and “stake-outs” in the New York Public Library.

Toward the end of his life, his taste changed, moving away from the great iconic artists of the 20th century and exploring unknown artists. Some such artists remain unknown and unconsidered, but after his death, Alcoa Corp. was persuaded to buy a group of this latter work for its own collection. Included were little-known paintings by Alberto Burri and Victor Vasarely. When Alcoa dispersed its art collection in 1995, the prices for the Burris alone again confirmed Thompson’s prescience, selling for somewhere between $250,000 and $750,000.

After Thompson’s death in 1965, Sotheby’s sold 113 of his paintings and sculptures for what was then astronomic prices. On the death of his widow, Helene, in 1982, a Monet made $1.2 million at auction, a Klee $467,000 and a Picasso $363,000.

Nor is that the end of the story. The Thompson estate is not yet completely exhausted. Concept Art Gallery in Pittsburgh has occasional sales, which include material once owned by Thompson. Last year his daybed and other furniture made by the Danish designer Poul Kjaerholm made high prices. It is interesting to note that in the redesigned Museum of Modern Art, identical pieces of furniture by Kjaerholm have been included in the design of the galleries. Put bluntly, the story of G. David Thompson is not over, and it may well be that only now has his time come. It is often better to consider difficult characters posthumously.