Mill 19: A Magnificent Blend of Past and Future in Hazelwood

At an early September opening for Mill 19, the new robotics research incubator and office space in Hazelwood’s former LTV Steel site, a robotic arm participated with scientists and dignitaries to help cut the ribbon in the voluminous lab space with a high-tech flourish. Tenants include Carnegie Mellon’s Manufacturing Futures Initiative and the affiliated nonprofit Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing, as well as Catalyst Connections, an employment training organization. CMU President Farnam Jahanian extolled the “new era of manufacturing,” in which researchers will advance robotics, artificial intelligence, and 3D printing from lab experiments into real-world industrial uses. The future is here.

So is the past. Mill 19 transforms and reoccupies the remaining superstructure of a former rolling mill for LTV Steel, a structure that was designed to support three separate 40-ton cranes. At over 1,200 feet long, it is one and a half times longer than the fraternally rusty US Steel Tower is tall. Don Smith, president of RIDC, the building developer, says Mill 19 “was the last real mill building on a site which was once just an enormous steel complex.” He and others admired the huge scale and distinctive profile.

RIDC held a design competition to best determine the possible schemes for reuse. Minneapolis-based Meyer Scherer Rockcastle, a firm with experience adapting decaying industrial structures won over clumsier schemes for expensive reskinning or partial demolition. Their proposal to peel away the flimsy blue sheet metal skin that once covered the building, expose the much more dramatic steel skeleton, and install a sequence of office and lab structures was not originally self-evident. “Only after some work and discussions and analysis did it become clear to [the architects] that this was the right thing to do,” says MSR principal architect Tom Meyer.

The designers increased the architectural drama by leaving a long, full height corridor of open space between the new inner buildings and the old exterior frame, treating it as a public passage, while allowing walkways and balconies to extend from the offices at upper levels through the interstitial space and outside the industrial skeleton to go down via stairways to the ground.

Mill 19’s transformation has been well-publicized, and early renderings accurately predicted the eventual project. Yet, in real life, the architectural interweaving of modern labs and industrial ruins is viscerally satisfying. With blue and gray panels on different portions of the lab building, yellow for the exterior staircases, and orange on some structural steel, there are echoes of the British High Tech architects of the 1960s and 70s, but really, this is all Pittsburgh. Where else can you find so compelling an architectural embodiment of high-tech resurgence and ecological landscape within the mammoth rusty ruins? And what combination better unites the historical and forward-looking currents of our identity?

The outdoor corridor is enhanced notably by a linear landscape, designed by D.I.R.T. Studio and 10 x 10, which reincorporates new and salvaged concrete block into a rain garden with native plants, making the transition from abandoned industry to revitalized natural and human-made environment seem measured, geometric and beautiful, a contemplative setting for the post-industrial promenade.

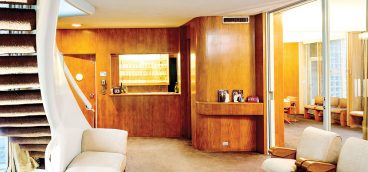

Entering the building, it becomes all business. A double-height lobby has expansive windows that reveal office and conference spaces on two floors. The mix of interior spaces, by R3A Architects, is efficiently utilitarian in the labs and high bay space, while offering just a hint of streamlined style, perhaps with a winking seventies undertone, in the offices. CMU Associate Vice President for Campus Development and Facilities Design Ralph Horgan notes that a major conference room is available for use to Hazelwood community groups, as part of the space occupied by Catalyst Enterprise.

Mill 19 is still very much a construction site with two of three office buildings within the old steel frame still in process and different infrastructure projects under way on a mile-long brownfield that has some flurries of activity amid some vast empty expanses. The early appearance of complete streets, with ample sidewalks and bike lanes, amid the emptiness is a little bit eerie.

The fact that the first phase of office and lab space is operational is all the more remarkable. It is purposeful and well-executed. A smooth exterior wall finish might have been a better contrast to the rough, oxidized superstructure than the corrugated panels on some of the walls, but that is secondary to the primary experiences.

With the necessity of security for technological research and industrial secrets, nobody is going to just wander into this building without an appointment and a sign-in, so the presence of dramatic spaces and architectural experiences on the exterior is suitable. Another showcase element, the two-acre plaza by landscape architects Gustafson Guthrie Nichol, includes a variety of gardens and a water feature, as well as concrete elements to facilitate seating for gatherings and performances. It is still under construction. The development partnership sees this feature as an amenity for the community, with programmed events and activities to draw attendees from the nearby neighborhood.

Steel-era Pittsburgh is like ancient Rome. We too could go several more centuries before restoring the old ruins to the magnificence of their original capacity, and the reconnection to the Hazelwood neighborhood itself is still a stretch that no single building can solve. The triumph here that will encourage continuing growth is that no other building could convey simultaneously the stunning collapse and the ambitious transformation quite the way this one does.