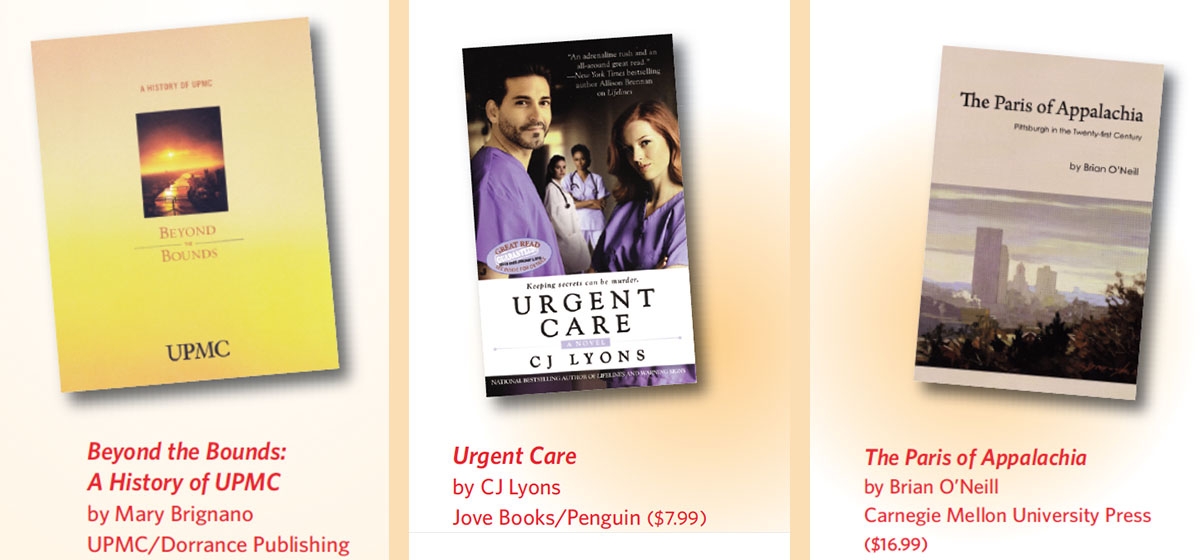

Corporate histories commissioned by the client are seldom (read never) impartial, and UPMC’s “Beyond the Bounds” is no exception. Author Mary Brignano lays on the praise in this glossy tribute to UPMC founder Thomas Detre, M.D., and his protégé, current President & CEO Jeffrey Romoff.

Their accomplishment—the transformation of a parochial medical center into the international healthcare behemoth at the center of Pittsburgh’s new economy—is indeed tremendous, and makes a good story for those who can stomach superlatives. Like any good story, it features struggles, triumphs and a captivating protagonist.

Astute, efficient and uncompromising, Tom Detre in his prime may have been a bureaucrat’s nightmare, but he is a novelist’s dream. The details of his life and personality are larger than those of mere mortals, and include an avant-garde upbringing in Budapest, a narrow escape from the Nazi death camps, and an iconoclastic, pharmacological approach to the treatment of mental illness in the Age of Psychoanalysis. At midlife he walked away from a tenured position at Yale and swept into sooty, hidebound Pittsburgh, determined to clean house at Western Psych in the 1970s. Possessed of an unusually healthy ego (“There are people who inspire confidence. I happen to be one of them.”), a Count Dracula accent, and an ever-present ebony cigarette holder, he led the myopic nerds at Pitt out of their jealously guarded ivory towers and into a new world of aggressive research, compassionate care, interdisciplinary cooperation and profitability.

Accompanying him were his wife, an esteemed epidemiologist; his crack psychiatric nurse, Vivian Romoff; and Romoff’s trailing spouse, Jeffrey, whose synoptic thinking and political-science training would eventually provide the tactical know-how indispensable to the rise of UPMC. The most poignant chapter of the story is certainly Vivian’s fatal illness at 37, which supplied an emotional impetus for the creation of the Cancer Institute, one of the earliest and most essential building blocks in Pitt’s medical empire.

Step by step, as funding was obtained and first-rate talent secured, successive institutions were brought into the fold, increasing the power and presence of UPMC until it reached its apotheosis in the last decade, supplan-ting U.S. Steel as the dominant economic and physical entity in the region. Today it is a worldwide leader in healthcare management, promoting the successful, synergistic “Pittsburgh paradigm” in Sicily, Ireland and elsewhere.

There is, of course, another side of the story, as hinted in the repeated references to resentment and opposition from presumably small-minded obstructionists. But there is no place for pessimism in this portrait of perfection, enhanced by beautiful, golden photographs of Pittsburgh that make it easy to believe in a happily-ever-after for our city.

Pediatric emergency physician CJ Lyons provides a very different take on the local medical community in her latest romantic suspense novel, “Urgent Care.” Except for a few allusions to a meglomaniacal CEO, the organizational realm of healthcare is far away, with no tiresome boardroom negotiations or lofty talk of broad visions. It is all action, all the time. Accustomed to the pace of the ER, the author hits the ground running, with a nude corpse on page two, and never stops, combining sex, psychosis and scabies (among other ailments) in a frenetic thriller guaranteed a great-read-or-your-money-back by Penguin Group USA.

This is the third volume in Lyons’ popular Angels of Mercy series, which debuted in 2008. Structured around the personal and professional tribulations and rather alarming physical dangers encountered by four smart-n-savvy women in a Pittsburgh medical center, the books abound with local references, from East Liberty crack houses to the Allegheny Country Club, Iron City beer and pierogies at the Bloomfield Bridge Tavern. In this installment, a slutty nurse anesthetist is discovered raped, murdered, and covered in neon graffiti in the cemetery adjacent to the hospital, reviving the repressed memories of charge nurse Nora Halloran, who “must face her deepest fears and reveal all her secrets to stop a killer from striking again.” Along the way, she irons out an unusual misunderstanding with her sleepwalking former lover and learns to forgive herself for being vulnerable. All the while, she and her sisters in healing handle a daily routine of lifesaving in spite of defiant patients, pompous doctors, and penny-pinching administrators. They are supported by dream boyfriends of a purely fictitious nature, with action-hero jobs and sensitive natures; big on listening and hugging, but able to kick down a door when the story requires it. However, Lyons keeps the pages turning at a clip that allows no time to dwell on the implausibility of the plot. Even readers who ordinarily eschew this type of fiction will find themselves suddenly at the end, slightly dazed and guiltily pleased. Diagnosis: Diversion.

The title of Post-Gazette columnist Brian O’Neill’s collection of essays, “The Paris of Appalachia,” evokes the famous advertising slogan, “The Champagne of Beers.” Although intended to lend cachet to their subjects, these terms nevertheless connote an inherent inferiority. After all, even the champagne of beers is still beer and The Burgh (as we are constantly reminded) ain’t Paree. O’Neill’s choice, therefore, is perfectly suited to this tribute to, and gentle rebuke of, his adopted home town: the “great good place” where “almost all of us are ready to embrace our inner rube”; the Little City That Could—If It Really Wanted To.

The thing is, it doesn’t really want to, as the author notes with bittersweet exasperation. Pittsburghers actually cherish their second-best status, as O’Neill illustrates in an apt sports analogy. For 40 years, former Pittsburgh Pirate Bill Mazeroski, hero of the 1960 World Series, was omitted from the Baseball Hall of Fame. When his true worth was finally formally acknowledged in Cooperstown in 2001, local fans experienced euphoria—immediately followed by a sense of loss. “The underdog,” O’Neill notes, “had become an overachiever.”

If, like Maz, Pittsburgh were really and truly recognized (as opposed to being granted lip service) as a world-class city, some of the things we enjoy here—such as housing values, simple commutes and a strangely satisfying, self-pitying identity—would likely disappear. And so, Pittsburghers are resistant to change. The author himself suffers from this affliction, expressing concern about the wrong kind of change, which might result in a decline in the quality of life he and his family enjoy. He loves to walk to work, shoot the breeze in his local tavern, and send his children to a well-integrated public school. He wants the city to move forward, but retain its friendliness and quaint insularity. He worries about us “becoming a nation of subdivisions punctuated by chain stores,” and the extinction of the generation that perpetuates the “holy starch fests” of “Hunky soul food” in church basements. Even so, he pleads with readers to reform the deficiencies of municipal government by overthrowing the “one-party rule” of the Democrats that discourages innovation, and restructuring the city’s splintered political map, defined as it is by “buggy-aged boundaries.” Only these—gasp!—changes will ensure the city’s future and allow us to retain all that makes it special.

But O’Neill admits one should “never discount the power of inertia” and ruefully acknowledges the presumed futility of his efforts, observing that even those who care enough about Pittsburgh to have opened his book “likely prefer [he] get back to those stories where beer was involved.” True, dat.

In a city whose suggested motto is “We Keep Doing What Doesn’t Work Because We Always Have,” this book isn’t likely to spur a revolution, but it does provide something to think about, some things to laugh about, and a lot to appreciate.