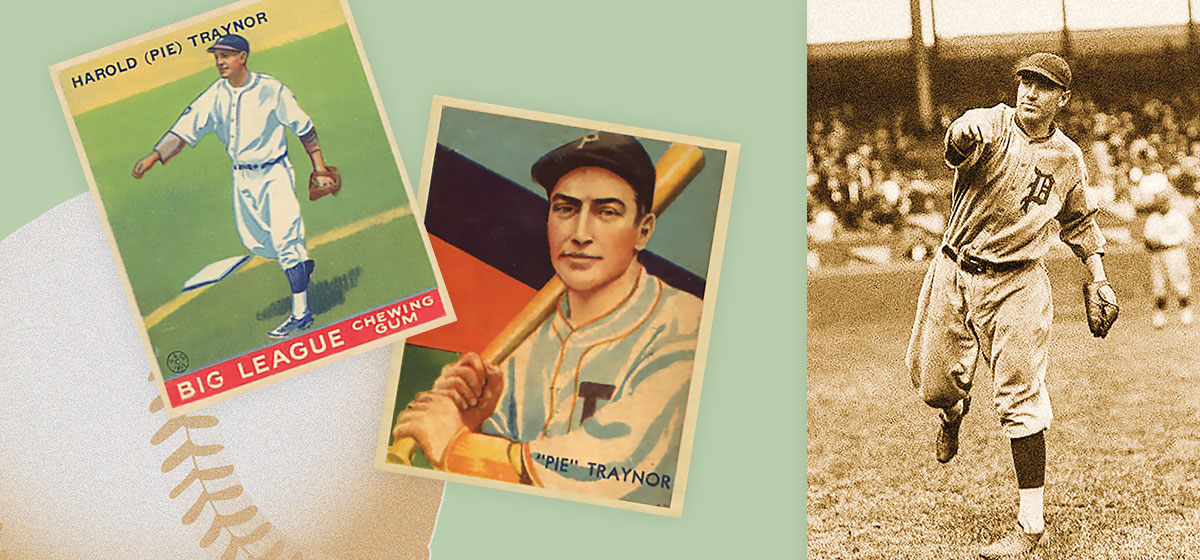

Original research for this story was conducted by the author for a book he co-authored with David Proctor entitled “Pie Traynor: A Baseball Biography.”

Hunched over a lathe on a steamy factory floor, Pie Traynor — World Series champion, future Hall of Famer, and the man widely considered the greatest third baseman who had ever lived — was looking for an exit.

Traynor had wandered a twisty road from the baseball diamond to the metal shop. Growing up in the Boston area, he learned the game as so many others did, playing pick-up games on the local sandlots. (Legend has it that as a youngster, he bought himself a slice of pie on his way home from the playgrounds, which is how he came by his unusual nickname.)

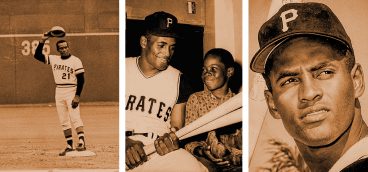

Despite his weakness for sweet pastry, Traynor matured into a formidable ballplayer with a powerful arm and exceptional speed. Professional scouts took notice. After just one season in the minor leagues, Traynor made his Pittsburgh Pirates debut in September 1920, and over the next decade-plus he dazzled fans with his dashing style of play. His 2,416 hits still tie him for fourth on the club’s all-time list. With his glove, he conjured miracles.

After an ailing shoulder snuffed out his playing career, Traynor took over as Pirates manager in 1934. Prone to pessimism and averse to confrontation, Traynor struggled to control his clubhouse and spent most of his tenure an emotional mess. A catastrophic late-season collapse in 1938 and a disappointing sixth-place finish in 1939 led to his dismissal. As the 1940s dawned, he was out of a job and out of a baseball uniform for the first time in his adult life.

Like many former athletes, Traynor was ill-prepared for life away from the field and he floundered for a while. His first move was to relocate to Cincinnati, near his wife’s hometown, where he sold cars at a Lincoln-Mercury dealership. In October 1942, with World War II raging, Traynor tried unsuccessfully to enlist in the U.S. Army, a rejection he called the biggest disappointment of his life. Too old to fight at age 44, but restless for a sense of purpose, he instead took a job fabricating parts for military aircraft.

It was honest work. Noble, even. But it couldn’t sustain him for long. In Cincinnati, Traynor was just another face at the plant. In Pittsburgh, he was a star — a popular after-dinner speaker, a willing instructor at baseball clinics and a soft touch for endless autograph seekers. Sometimes he grumbled about the demands on his time, as if he couldn’t live with all the adulation. In truth, he couldn’t live without it.

So, in February 1945, Traynor pounced on an offer to return. He accepted a position at radio station KQV, and over the next quarter-century became one of the most beloved media figures Pittsburgh has known.

Traynor hosted “The Hot Corner,” a 15-minute review of the day in sports that ran Monday through Saturday at 6:30 p.m. The Pittsburgh Press believed he was sure to be a hit. “He has the perfect voice, with just enough of New England in it to make it smooth.” Indeed, he was successful, but smoothness had nothing to do with it. As Traynor’s KQV colleague Keeve Berman joked, “You took your life in your hands when you gave him a live mic.”

Traynor was a witty storyteller and a delightful conversationalist, but he never quite got the hang of radio. When the microphone flipped on and the clock started ticking, his eloquence melted into an amalgam of awkward pauses, mind-bending malapropisms, and inexplicable stammering.

Traynor flubbed the name of the New York Yankees’ star catcher, rechristening Yogi Berra “Yoga Berry.” Niagara University turned into “Nicaragua University.” Ads for Monroe Super Load-Levelers, a brand of shock absorbers, repeatedly became ads for “Monroe Supler Load-Levelers.”

One night Traynor sat down with a painfully shy heavyweight boxer named Johnny Flynn. As the story goes, he began the interview by asking, “How do you think you’ll do in your fight tonight?” Flynn, seized with mic fright, turned mute. Unperturbed, Traynor fired another question, and another, and another, as Flynn stared back in slack-jawed silence.

“People were calling into the station saying, ‘Something is wrong. I’m only hearing Pie Traynor’s voice!’” chuckled KQV’s Alan Boal. “He just went ahead with things like that when he didn’t understand what was going on.”

Traynor drew listeners, though. His knowledge of sports was encyclopedic and his clumsiness, which would have doomed another broadcaster, came off as endearing and innocently goofy.

KQV learned to not question what worked. On an afternoon when Traynor had to record his program in advance, a newly hired engineer, Paul Carlson, took the initiative to edit out all the stumbles before airtime. The Traynor that emerged sounded like a valedictorian at the nation’s finest radio school: articulate, polished and professional. And completely wrong.

“You can’t do that!” Berman roared at the befuddled young man. “You killed Pie!”

Carlson learned his lesson. “The artistry,” he told radio historian Jeff Roteman, “belonged to the artists.”

For most of his tenure at KQV, Traynor lived in Oakland. Although he once sold cars, he never learned to drive, which meant a long walk to and from the station’s Downtown studios. It was a two-mile stroll that took hours. He could barely take three steps without someone stopping him.

“Wherever he may be, Traynor has chain conversations,” wrote Roy McHugh in The Pittsburgh Press, “the other participants coming and going, new faces joining in the dialogue or one [making] room for another.”

Chance encounters with Traynor on the sidewalk became part of daily life for a generation of Pittsburghers. Chuck Reichblum of KQV described Traynor as “the friendliest celebrity I ever saw. He had no pretense at all. A little kid would come up to him and say, ‘Hi, Pie.’ There was no ‘Mr. Traynor.’”

Pittsburgh Steelers publicist Ed Kiely marveled at Traynor’s patience. “I don’t think I ever saw him have a bad moment or brush off anybody. He would stand and talk to [fans] as if he knew them for a couple of years.”

Traynor departed KQV in 1966. His sports reports, long since reduced to five minutes, had fallen out of step with the station’s Top 40 format; furthermore, his worsening emphysema made it difficult for him to meet his daily responsibilities. However, by this time Traynor had become a regular presence on television, as part of WIIC’s live Saturday evening broadcasts of “Studio Wrestling.”

Traynor was the spokesman for the American Heating Company, one of the show’s longtime sponsors. American Heating had discovered an underserved market niche — blue-collar customers who didn’t have much cash lying around to pay a contractor.

“Back in the ’60s, it wasn’t real common to get a loan from a bank to get a roof fixed,” according to Jack Berger, son of the company’s founder, Max Berger. “My dad worked closely with Mellon Bank to let people buy things on credit. The Heinz family wasn’t calling American Heating.”

These were folks who might have paid a dollar to cheer on Traynor from the grandstand at Forbes Field years before. They also were the kind of people who enjoyed professional wrestling. “When we had wrestling on, we outdrew the Steelers,” declared Bill Cardille, who hosted “Studio Wrestling” beginning in 1961.

Between matches, Traynor strode to ringside and read the ad copy off a teleprompter. He punctuated his pitch with the tagline, “Who can? Amer-i-can!” One of the rare recordings still in existence is somewhat uncomfortable to watch. Traynor looks like he is performing at gunpoint, standing straight as a lamppost and barking out his lines with almost no intonation or facial expression.

“He was afraid to make a mistake,” said Cardille. “He wouldn’t take his eyes off the teleprompter. If they wrote ‘Go fly a duck’ on the prompter as a joke he would have said, ‘This is Pie Traynor. Who can? Amer-i-can! Go fly a duck.’ It was full steam ahead, damn the torpedoes.”

The campaign almost seemed like a parody. Reichblum worried that Traynor came off as “clownish,” while WIIC announcer Don Riggs thought he became “a caricature of himself.” Traynor’s friend, groundbreaking news anchor Eleanor Schano, even interceded with the advertising agency, begging them to help him appear more natural and relaxed.

But neither American Heating nor its agency wanted to change anything. Viewers remembered the spots and talked about them, and the tagline became a local catchphrase. On Traynor’s daily walks, strangers called out, “Who can? Amer-i-can!” Traynor may have inadvertently made viewers laugh, but he also made them buy.

“Those ads would routinely bring in a number of phone calls that would turn into leads,” according to Jack Berger. By the time his father sold American Heating in the 1990s, he had grown it into one of the largest home improvement companies in the Pittsburgh area.

More than a public figure, Traynor became almost public property, a living civic institution. Following his death in March 1972, his funeral services attracted, as Roy McHugh wrote, “the young and the old, the rich and the poor.” Sports figures, politicians, and business executives, of course, but also security guards, stadium ushers, young children and others Traynor touched, directly or indirectly, long after his baseball days had ended.

Baseball Hall of Fame director Ken Smith flew in from spring training in Florida. He was there in his professional role, but for him, like so many others, it was personal, too.

“This guy,” Smith marveled, “there was nobody like him.”