Joe Louis was the man. Everyone in the country knew his name. He was heavyweight champion of the world when the title was the most prized crown in all of sports and carried more prestige than the biggest Hollywood star.

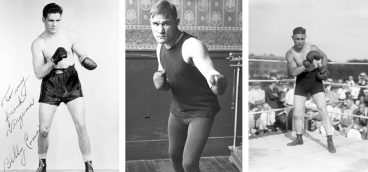

The light-heavyweight championship, on the other hand, had all of the stature of the winner of a prettiest pig competition. In 1939, the title-holder in the light-heavyweight division was John Henry Lewis, who was living and training in Pittsburgh. Twenty-four years old, smart, dashingly handsome and a technician in the ring, Lewis had become the first black American light-heavyweight champion in history in 1935. He should have had it all. Unfortunately, he was born just a bit too small.

The biggest difference between the heavyweight champion and the titlist at other weight divisions was the size of the payday. So when the time came for John Henry Lewis to take on the ferocious-hitting Joe Louis—the Detroit Destroyer—it didn’t matter if he was concealing the fact that he was blind in one eye. This was his one and only shot. Fight the Brown Bomber or die on the vine.

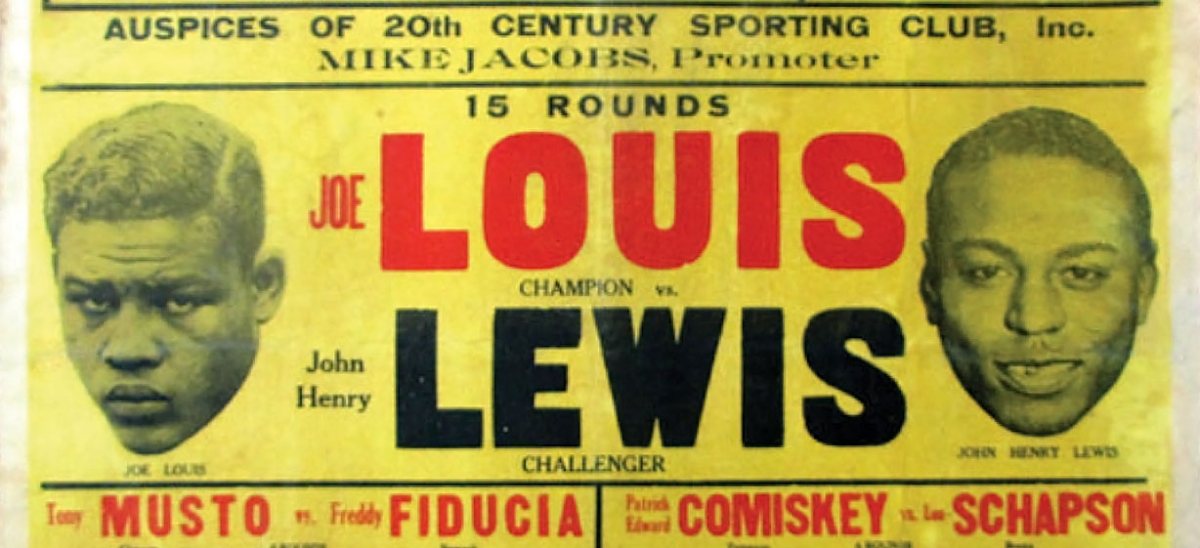

On Jan. 25, 1939, Louis and Lewis made history, the first heavyweight championship fight in America featuring two black men. John Henry Lewis would never fight again.

The pride of Phoenix

Born in Los Angeles in 1914 and raised in Phoenix, Lewis was taught to box at age 4 by his father, John Edward Lewis, a former lightweight who ran a Phoenix gym. Boxing was in the family blood, with John Henry’s great-great uncle being the noted bare-knuckle brawler Tom Molineaux.

By the age of 5, Lewis and his brother, Christy, were battling in exhibition “midget boxing” matches. He turned pro at 14, as a welterweight, and gained a reputation for outstanding speed and increasingly superior boxing skills. Three years later, in 1931, Lewis won his first championship, the Arizona middleweight title, and the following year, still in high school, the “Pride of Phoenix” beat future heavyweight champ, “Cinderella Man” James J. Braddock, at San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium.

Lewis finished 1932 with one loss in nine fights. He didn’t lose in 1933, and the next year, he lost once, when Braddock returned the favor during his celebrated “Cinderella” run for the heavyweight crown. But for Lewis, despite winning 15 bouts in 1933 and 1934, his career seemed to be going nowhere. Barely 21, his prospects for making a living in the sport looked bleak. He was passed over for the big fights and the title shots. His crowds were thin and his purses were even thinner.

Coming to Pittsburgh

It all changed in 1935, when he came to Pittsburgh and signed with Hill District businessman Gus Greenlee to be his manager. William Augustus Greenlee, a.k.a. “Big Red” and “The King of the Hill,” is credited, along with William “Woogie” Harris, with bringing the numbers racket to Pittsburgh.

Born in 1895 in North Carolina, Greenlee hopped a train in 1916 to Pittsburgh, where he had an uncle. From the minute he descended the railcar in the dead of winter in sneakers and torn blue jeans, Greenlee’s success began. He rose from shoe shiner to cab driver to cab owner to bootlegger from his cab, and soon to numbers runner. After serving as a machine gunner in Europe in World War I, Greenlee returned to the Hill District and opened the Crawford Bar & Grill, attracting the top musical talent to its stage. The shoe shiner from the Blue Ridge Mountains was holding court with the likes of Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington and Lena Horne.

In 1930, Greenlee turned to the world of sports, purchasing the Pittsburgh Crawfords baseball team. The Crawfords soon boasted an almost obscenely loaded lineup, including Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Julius “Judy” Johnson and Leroy “Satchel” Paige. The 1935 squad not only won the Negro National League Pennant but was arguably one of the finest teams ever assembled.

At 6′ 3″, Greenlee was big in stature and in heart. For neighbors looking to start a business or purchase a home, “Mr. Big” was the man to see. During the Depression, Greenlee set up soup lines and handed out turkeys. After watching his players be denied use of the dressing room when the Crawfords played on white-owned fields (all of the ballfields at the time), Greenlee decided to build his own stadium. In 1932, Greenlee Field became the country’s first black-owned stadium. Built of steel and brick, it cost $100,000 and was completed in six months—in the teeth of the Depression. The facility accommodated 7,500, and the Crawford players could get dressed as they pleased.

Greenlee Field also became the avenue through which he entered the fight game. Staging boxing matches was just one more way to fill a ballpark. Before long, Greenlee took the next step and began managing fighters. One of them was John Henry Lewis.

Greenlee welcomed Lewis to Pittsburgh and his Frankstown Road home, where he built a boxing camp in the backyard and Lewis lived in a cottage on the property. Lewis also trained and exercised at the Centre Avenue YMCA, where he swam and became one of the club’s top handballers. It took Greenlee just four months working with Lewis to set up the title shot that had eluded the young fighter. On Halloween night 1935, at the old Municipal Auditorium in St. Louis, Lewis outpointed New York’s Bob Olin in 15 rounds, becoming the first black American Light-Heavyweight World Champion in history. Greenlee became the first black man to manage a world champion.

Still, the post-championship road was anything but easy for Greenlee and Lewis. Even the ensuing victory celebration fell flat, as Greenlee only had to take a quick look at his wallet to understand the harsh reality of non-heavyweight economics. To get the Olin fight, Greenlee had to guarantee him $15,000. Promoters had expected a crowd of 20,000, but only 8,000 showed up. Lewis, who was to receive 12.5 percent of the gate after Olin’s guarantee, didn’t receive a dime. And after paying Olin, Greenlee left St. Louis with just $6.

Plight of the light-heavies

The 168- to 175-pound light-heavyweight class has been called “the graveyard division.” In the late 1930s, the decision for Lewis was clear—it was time to bring on the heavies. He would have to slug his way out of his weight class and into the money division in order for his career to stay afloat.

In 1937 and 1938, Lewis beat a string of heavyweights and split a pair of fights with Cuban heavyweight champion Isidoro Gastanaga. On Nov. 3, 1938, Lewis defended his light-heavyweight title, beating Al Gainer on points before an empty house in New Haven, Conn. Following the bout, the 24-year-old Lewis, a professional for nearly a decade, vented his frustration. He was done fighting for “peanuts.” For his efforts against Gainer, a New Haven bricklayer, Lewis netted $2,600. By comparison, Joe Louis had made $321,245 for his latest heavyweight fight against Max Schmeling.

Lewis issued a challenge: He was ready to take on anyone, anytime, light heavy or heavyweight, but the money had to be there. Less than a week later, Joe Louis’s team announced the champion’s next opponent: John Henry Lewis was going to get his shot and a payday.

“Boy, I’m happy,” Lewis said. “It’s the chance I have been praying for, and I’m going to fight the best fight of my life.” The fact that he could barely see out of his left eye didn’t matter. The light heavyweight who’d never had a profitable match as champion was in line to receive 17.5 percent of the receipts of a heavyweight title fight at Madison Square Garden.

The matchup would be the first heavyweight title tilt waged between two black men. It was marketed as a battle between a quick and crafty ring veteran versus the king of knockouts. The date was set for Jan. 25, 1939.

The runup

Joe Louis had a sledgehammer of a right hand. Unfortunately for opponents, his left was just as devastating. Plain and simple, Louis was a machine. He had one loss against 36 wins, all but six of those by knockout. In 1937, Louis had knocked out James Braddock in eight rounds to win the championship. And prior to signing on to battle John Henry, Joe Louis had gotten revenge against the man responsible for the lone blemish on his record, dismantling Max Schmeling in 124 seconds at Yankee Stadium. The brevity of the savage assault was nothing new. It was the 20th match Louis had put to bed in three rounds or less and the seventh in less than a round. He would often announce prior to stepping into the ring how long he’d “allow” the fights to go. Joe Louis was the man.

John Henry’s financial plight was not lost on Joe Louis, who called John Henry his friend. Asked why he agreed to the fight, Louis said, “I am doing it for two reasons. John hasn’t made any money since he’s been fighting. I want to give him a chance to pick up a decent purse, and I also want to silence a lot of big-mouthed guys. They have been saying that I’m scared to risk my title against John.”

Tickets sold quickly, with ringside seats going for $16.50 and $2 for general admission. The sport was huge in the ’30s, and in newspapers across America writers penned boxing columns such as “In This Corner” or “Ring Dust” in prose that leapt from the page. Every boxer had a nickname, with their hometown often receiving prominent mention. Boxers engaged in “scraps,” or “cauliflower conflicts.” But the word “fist” was used with the most zeal, nuanced into practically anything, from “fistiana” and “fistdom” to the more liberally used “fistic.” It was fistic everything: “fistic fireworks,” “fistic fortunes,” “fistic wars,” and for Joe Louis’s power-packed punches, there was “fistic projectiles.”

Three days before the fight, Louis was a 6-1 favorite. But predictions flew fast. The expected sellout crowd was taken as a sign the public was expecting a close fight. Many in the fight game, old-time managers and ex-fighters included, foretold a 15-round decision, predicting that John Henry’s speed and experience would keep him from an early fall. The contest matched Louis, who’d knocked out 30 of 37 opponents, versus Lewis, who’d never been floored in what was considered at the time to be 99 fights. Something had to give.

The combatants represented themselves with class in pre-fight media sessions. They spoke no trash (known as “fancy talking” at the time). They kept responses simple. “John’s my friend,” said Louis. “I wasn’t anxious to fight him… but if he wants to fight, I’ll be out there to win as quickly as I can, and I’m gonna keep that title.” Replied John Henry, “I’m not afraid of Joe or anyone else.”

Both fighters realized what was at stake. John Henry was at a crossroads. This was his opportunity. For the champ, the task was one he didn’t take lightly – holding onto his beloved belt.

At 11:45 a.m. on Jan. 25, the two men met for the weigh-in at the State Athletic Commission headquarters in downtown Manhattan. Outside, gale force winds of up to 52 miles an hour wreaked havoc on the city, as temperatures battled upward following a recent single-digit cold streak. Across town at the Apollo Theatre, a young Ella Fitzgerald was singing with the King of Swing, Chick Webb.

“How do you feel, John?” Louis greeted his friend. “All right, Joe,” John Henry replied.

The talk was finished, and the room markedly quiet. The 25-year-old Louis weighed in at 200¼ pounds. The challenger, 12 days Louis’s elder, checked in at 180¾ pounds, at least four pounds off his goal and nearly seven pounds down from his weight just a week earlier during training camp.

The champ was cool and relaxed, while John Henry was said to be ill at ease. Commission physician, Dr. William Walker, described Lewis as “thoroughly dried out and extremely nervous.” Unknown to the challenger at the time was the fact that Gus Greenlee’s younger brother and John Henry’s close friend, Dr. Marcus “Jack” Greenlee, had been killed in a car crash the night prior in suburban Pittsburgh. Lewis’s heavy-hearted handlers kept the news from him, so something else must have been bothering Lewis. The prospect of facing the punishing champ with only one good eye no doubt played a part.

In the morning papers, the betting line had widened to 8-1 for Louis. Wagering was surprisingly light. Few were willing to put money on Lewis, and the champ’s line was prohibitive; by fight time, it was expected to cost $10 to win $1 back on Louis.

By 10 p.m., 17,350 men and women, J. Edgar Hoover among them, filed into their Madison Square Garden seats. Hollywood starlet, Norwegian Olympic figure skating champion and purported quisling Sonja Henie also was on hand, turning heads as she made her way through the crowd. Henie was Louis’s flame at the time, and one newspaper man described her as “dolled up and fit to kill.” The fight would be broadcast coast-to-coast by NBC radio. Announcers Clem McCarthy and Edwin C. Hill had the call.

The bell

Two minutes and 29 seconds was all it had taken. The champ returned to his dressing room with his hair in place. Not a bead of sweat marred his million-dollar forehead. John Henry sat confused at his locker. “All I wanted was a chance to keep on,” he said. “I’m not hurt. Yes, he’s a hitter. He makes your eyes go in and out like a turtle’s head when he brings that right across. And he hits you to the body like he had a baseball bat in his hand.”

The fight was over in a flash. John Henry came out silky smooth with feet moving. He started with a left hand and missed, just buzzing Louis’s ear. It was the closest he got to laying leather on the champ. Moments later, a Louis right hand dropped John Henry for a count of three. The look on John Henry’s face turned empty and the “Stalking Shuffler,” Louis, moved in like a lion eager to finish off his prey. A heavy right hand to John Henry’s jaw shot him into the ropes for a second knockdown. Referee Arthur Donovan counted to two.

Fighting continued with a final Louis barrage at the two-minute mark. A right to John Henry’s left eye. Another right. The crowd screamed for referee Donovan to stop the fight. A left, and then one final thunderous right hand. Lewis was splayed on the canvas. Blood trickled from his mouth.

“His eyes were as vacant as an unfinished house,” wrote Harry Ferguson for the British United Press. Heart and instinct were all Lewis had left, and combined, they were enough to miraculously bring him to his feet, but Donovan halted the count at five. It was the second-shortest heavyweight title bout in history.

For the champion, everything went according to script. “I got a system. Knock ’em out quick.” For the challenger, whose payday was more than $15,000, it was as if he hadn’t seen the punches coming. The truth was about to come out.

Aftermath

On Feb. 1, a headline read: “Report Persists That Joe Louis Defeated ‘Blind Man’ in John Henry.” The national report by Harry Grayson stated that John Henry had been dealing with the eye injury for years. “Something in connection with the delicate mechanism of John Henry Lewis’ left eye is said to have snapped when the Phoenix Negro was struck in a workout a couple years ago.” The next month, Michigan Boxing Commission physicians confirmed that the sight in Lewis’s left eye was “almost nil.”

On June 19, the National Boxing Association stripped the light heavyweight title from Lewis because he was unable to defend it within the requisite six-month period due to the eye injury. Three Pittsburgh physicians confirmed the previous “diagnosis made by physicians in Michigan and London that Lewis was unfit to enter the ring because of partial blindness.”

John Henry Lewis, just one month past his 25th birthday, would never box again. Upon his retirement, Lewis confirmed that he had been fighting blind in one eye for three years: “I hoped nobody would catch me.”

Lewis’s final record stands at 103-8-6. After retirement, he left Pittsburgh for West Oakland, Calif., where he ran a boxing gym. He would eventually have his left eye removed.

Lewis and his wife, Florence, had two children, a son, John Jr., and a daughter, Tarika.

Lewis remained close with Greenlee until Greenlee died in 1952, and Lewis often reminisced about Pittsburgh’s close-knit African American community, its athletes and performers, said his daughter Tarika, who remembers well her father’s stories about Joe Louis and her father’s one last boxing payday.

“They were friends,” she said. “They both knew he had lost his sight in his eye. Louis knew my father wouldn’t be able to fight anymore, that his career was ending, so they decided, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to have this fight—Louis vs. Lewis?’ “

Lewis died in 1974 at the age of 59, after suffering from emphysema and Parkinson’s disease. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1994.