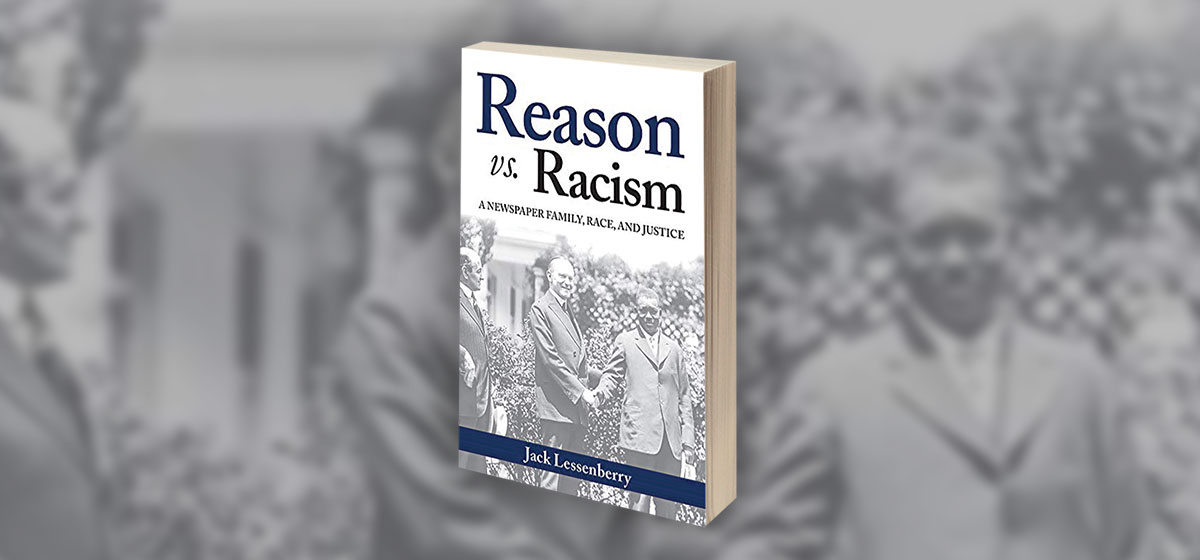

Looking at the Block Family’s Record on Race

Book reviews traditionally talk about what’s in a book, but almost never about how a particular book came to be.

This one has an interesting and unusual beginning. Nearly three years ago, following a controversy over an editorial called “Reason as Racism,” Allan Block, the chair of Block Communications, Inc., the parent company today of both the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the Toledo Blade, asked me to consider an unusual assignment.

His family had owned newspapers for more than a century, since his grandfather bought the Newark Star-Eagle in 1916. “I think we have a pretty good record as far as race is concerned, but I don’t know everything. Would you be willing to completely research our record, looking at every paper we ever owned, and write a book?”

I was intrigued. I taught journalism history for years, and have always been interested in the history of race in America and in the media. But I didn’t want to write anything less than the full story.

Block told me not to worry. “Write whatever you find, even if it makes us look bad. I only have one demand: That the research be as complete as possible. Read every page of every newspaper we’ve ever published.” I knew his grandfather owned papers in many cities, and that many of those papers only exist on microfilm in those towns.

I told him that, and he said, “In that case, go there.”

So I did. Over the next year and a half, I read old newspapers in libraries from Duluth to Detroit; from Pittsburgh to Milwaukee; from Nashville to Newark, Brooklyn and Lancaster, Pa. and more.

I went forth with an endless supply of thumb drives, and more helpfully, with Elizabeth, a brilliant archivist who is my better half. No, I did not read every page of those newspapers (sorry, Allan) but I read many hundreds of them, and other supporting material.

And to my surprise, I found enough great stories to make several movies. The Block family’s record on race was by no means perfect, but it was truly exceptional.

In 1925, Paul Block’s Memphis News-Scimitar lionized a poor black laborer who had saved more than 30 people from drowning, and took him to meet the President. But outraged local racists essentially ran Block out of town.

The Block papers won a Pulitzer Prize for revealing that despite his denials, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black was a life member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Ten years later, in 1948, a light-skinned white chicken farmer, who happened to be the best investigative reporter the Post-Gazette ever had, disguised himself as a black man and risked his life to expose the worst evils of Jim Crow — and was cheated out of the recognition he deserved.

The family’s record on race wasn’t perfect; they employed no black journalists before World War II, and like most papers, often ignored events in the black community. They sometimes dropped the ball on local civil rights coverage in later years.

But they were substantially ahead of their times, and did have black reporters and editors before almost any other of America’s great daily papers did; as early as 1951, the Toledo Blade sent its star black reporter on a long odyssey to report on race in America — and had him do it twice more over the decades.

Harry Truman, the president who integrated the armed forces, liked to say, “There is nothing new in the world except the history you do not know.” I learned a lot of both interesting and significant history reporting the stories in this book. I only hope I have told them as compellingly as they deserve.