Longing for Limelight

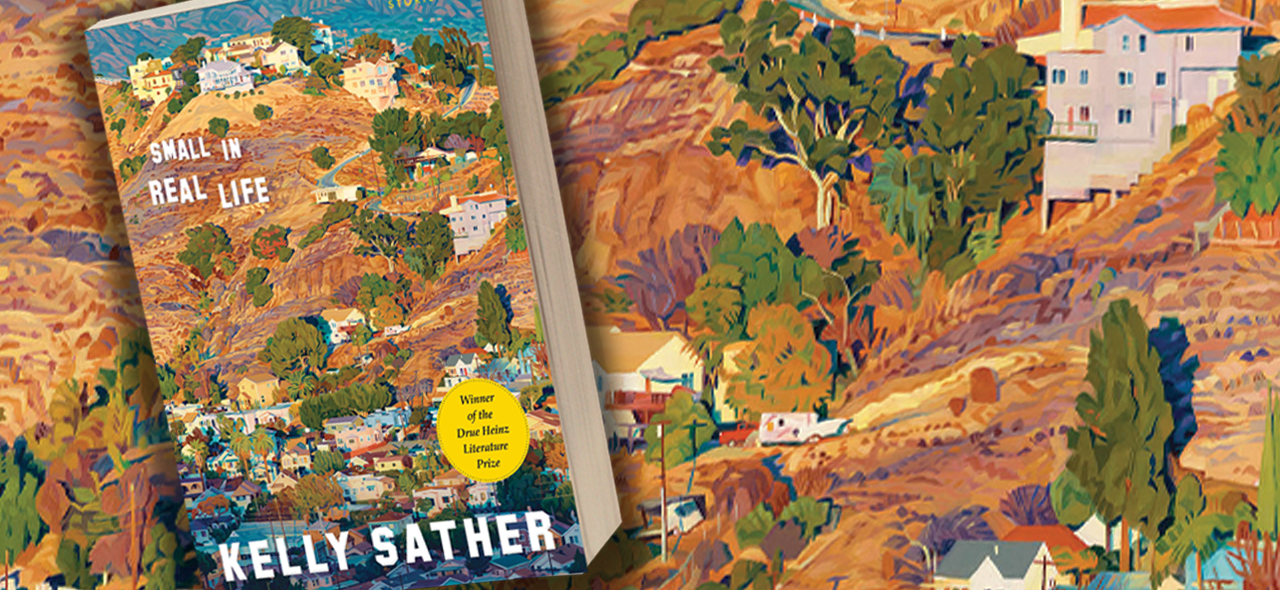

Hollywood has been alternately described over the years as “a tissue thin façade full of self-important narcissists” and “a place where dreams come alive.” This year’s winner of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize, Kelly Sather, paints her protagonists as dreamy, never-will-bes who dwell in the shadows of fame. The California native and former entertainment lawyer has crafted a world where the American Dream has been both realized and realized to be a sham.

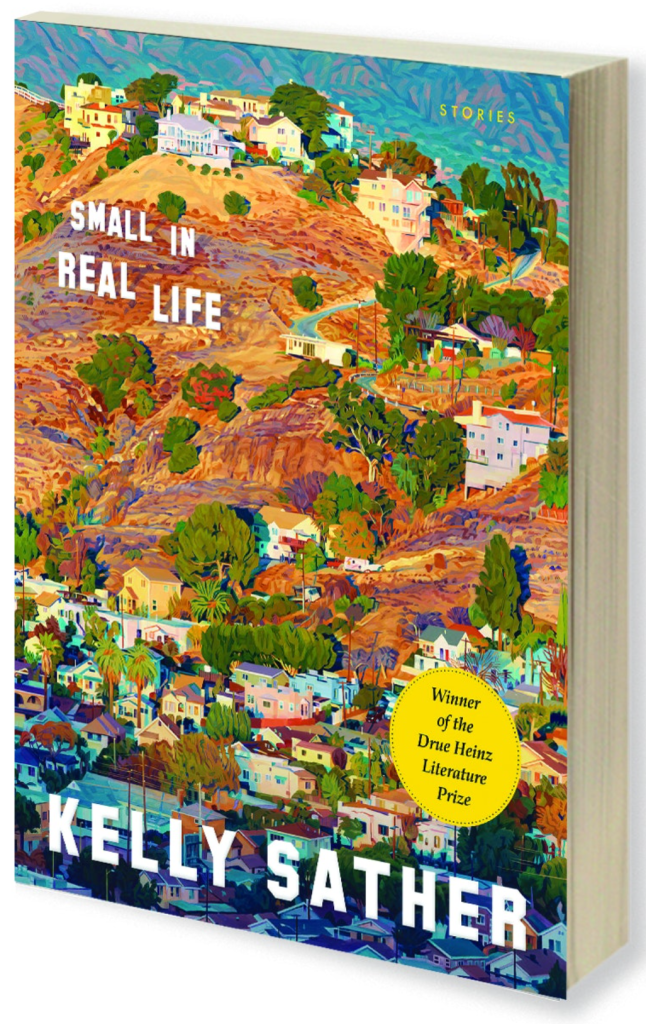

In her short story collection, Small in Real Life, her writing points toward Raymond Carver’s gritty realism and Nathanael West’s satiric desperation. In the title story, Louis has flown in to see his one-time bar band’s former manager Jay, now a thriving movie producer, at his Hollywood Hills home where a premiere party is being thrown. A New Jersey musician once on the cusp of success, Louis has been reduced to playing “backup guitar at a bat mitzvah celebration” and “selling AV equipment in a windowless cement box off Route 9.” That Louis doesn’t yet see his scheme to gain a foothold with the glitterati as foolish is par for the course. Or, as his wife who’s about to leave him cooly says of his attempt at fame, “You try in all the wrong directions.”

Kelly Sathers

The University of

Pittsburgh Press, $24.

Sather’s stories are populated with protagonists hellbent on remaking themselves, perfect for the ethos of a town where stage names and plastic surgery abound. A favorite, “Red Bluff,” set in 1974, has Tessa Dean sneaking “out of Camp Weyamucca with her best friend, Barrett Winslow … having better things to do than float a canoe across the lake or shoot an arrow at a bulls-eye nailed to a stack of hay.” With a plan to track down a makeup artist cousin in Hollywood, they enlist the help of an older teen who works at a nearby gas station. Sather nails the story’s ending by navigating familiar tropes and adding some new shine, leaving the ending as a plot twist certain to have imaginations running wild.

In, “Harmony,” tables get turned as a paparazzo, Paul, winds up in a Malibu rehab looking to avoid jail time after a fatal drunken-driving accident. The posh center is where he’s tasked with getting photos “OF THE F* UP AND FAMOUS,” a demand given by his tabloid boss and girlfriend, Arianna. Things get interesting with the cinematic arrival of a famous actor, Dennis, as if on a film set. With Paul on a mission to get a photo scoop on Dennis, it’s the audience who’ll realize that both are opportunistic cynics concerned only with that which might infringe on their comfort. The base shallowness of these characters will leave many ready for either a shower or a stiff drink.

In “Venice,” the Collins family follows their SoCal father’s lead while vacationing at a luxury hotel, smuggling pastries from the dining room and enjoying sundaes for lunch. But for 15-year-old Caroline, it’s not quite enough adventure. Characterizing her as spending “a lot of time looking in the mirror at her front and her back, and if there wasn’t a mirror handy, thinking about what she looked like, while she trailed at least five steps behind her family around Europe,” allows Sather to call up the image of Connie from Joyce Carol Oates’ classic, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” And like so many other evocative and grubby characters, Caroline will soon find herself, in the tragic words of her father, “out of her league.”