Loaves and Fishes

In April 1966, the Pittsburgh Zoning Board of Adjustment held a routine hearing to consider a plan from four East End churches (Calvary Episcopal, First Methodist, Third Presbyterian and Shadyside Presbyterian) to open a coffee shop for young people at 709 Bellefonte Street in Shadyside.

Unlike some board hearings where neighboring property owners angrily opposed unsuitable uses for a location, no one spoke against this idea. After all, the sponsors were four of the most highly respected churches in the city, and their approach for reaching out to the estimated 10,000 East Enders ages 20–35 who were not affiliated with any church seemed like a wholesome purpose for the storefront formerly occupied by a ski shop. The board swiftly rubber-stamped the proposal and church volunteers began renovating the site in anticipation of a grand opening that summer.

The project was the brainchild of Rev. Stewart Pierson, the 29-year-old assistant rector of Calvary Church. He developed the concept after visiting Potter’s House in Washington, D.C., a church-run coffeehouse serving as a center for activism, the arts and community development. The Pittsburgh initiative would operate six nights a week from 8 p.m. to midnight with programs of folk singing, jazz, poetry and dramatic readings, short plays and discussions. Overall guidance would be provided by a board of trustees comprising men and women representing all four churches, and day-to-day operations would be handled by a salaried manager. Although secularly oriented, the coffeehouse was christened with the Biblical name Loaves and Fishes.

While coffeehouses had existed worldwide for literally centuries as meeting places devoted to conversation and the exchange of ideas, their appeal waxed and waned over time. They surged in popularity in America during the 1950s following the arrival of the laid-back Beat culture with its artistic “beatniks” who often congregated in these settings rather than in the alcohol-oriented taverns and bars commonly patronized by the “square” citizens. For entertainment, this new wave of coffeehouses frequently offered jazz combos as well as a venue for struggling poets to read their compositions. The folk music craze of the late 1950s and early 1960s found a ready audience in the coffeehouses.

In Pittsburgh, numerous artists moved into Shadyside throughout the 1950s and the district acquired an image as the only place in Allegheny County where one might encounter a man with a beard. It was a likely place for a coffeehouse to thrive and so, the Cappuccino Coffee House opened on Walnut Street in late 1959. The Lamplight Coffee House began on nearby Ellsworth Avenue two months later. Several similar establishments soon followed and within a few years Walnut Street was nicknamed “Espresso Row.” It was logical to place Loaves and Fishes in Shadyside not only because it was convenient for young people from the East End who were the target audience but also because the neighborhood would obviously welcome such a venture.

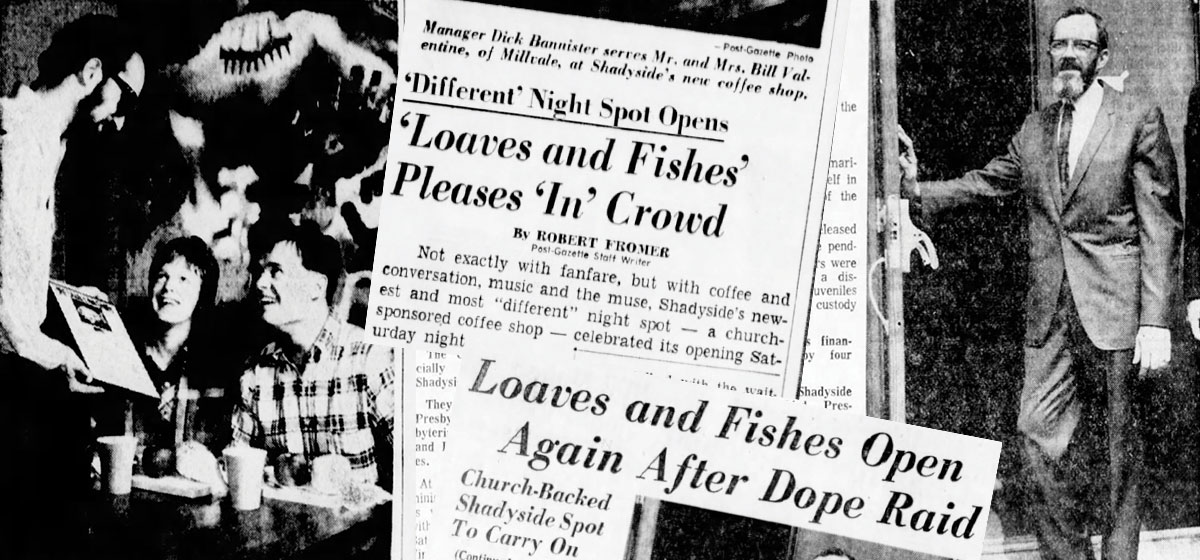

A photo from the August 20 opening night shows a clean-cut young married couple being served by Loaves and Fishes manager Richard Bannister. (Of course Bannister had a beard, as was de rigueur for the coffeehouse environment.) The menu listed eight different types of coffee among other non-alcoholic beverages plus light food offerings such as soup and fruit.

The evening started off slowly: the first customer was a 40-ish woman who dropped in shortly before the formal opening because she heard they were launching that night and she “wanted to see what it was like.” After a quick cup of coffee and a brief chat with the six waitresses who were the only other people in the place, she left. A half hour passed before the next guests arrived; they were a more promising bunch as three of the party of six were carrying guitars. Within an hour all 44 available chairs were filled and people were sitting on the floor. Loaves and Fishes remained packed until their midnight closing time. It appeared the church experiment was destined for success.

As the saying goes, however, the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry.

Two weeks after the well-publicized opening, coffeehouse manager Bannister was arrested for selling marijuana to an undercover Federal narcotics officer at a Walnut Street bar. Even though this transaction took place elsewhere, it reflected poorly on the new Bellefonte Street enterprise. Until his final sentencing nine months later, the local newspapers relentlessly chronicled Bannister’s travel through the legal system. Some folks who initially thought a church-sponsored meeting place for alienated young people was a fine idea were now reconsidering their position.

To their credit, the churches did not forsake Bannister during his time of trouble or second-guess their novel approach to youth ministry. In response to critics, senior ministers from the four collaborating churches issued a statement that clarified the mission and objectives of Loaves and Fishes. This statement read, in part: “The Church is a hospital for sinners and not a country club for plaster saints. … Some people are utterly horrified that the Church should even remotely touch any of the unpleasant realities of life. Our answer is that wherever people are in trouble, there we will minister to them.”

After a period of oversight by an interim caretaker, Rev. Richard Mowry was named as Bannister’s replacement in November 1966. As a Presbyterian minister he projected a better image than a pot-smoking beatnik, even though the 36-year-old Mowry also sported a full beard, unlike most clergy of the day.

As the brouhaha surrounding Loaves and Fishes and its indicted former manager dragged on into the new year, Allegheny County District Attorney Robert Duggan stepped into the picture. In his campaign for D.A. in 1963, Duggan ran on a platform of suppressing vice: gambling, prostitution, illegal alcohol sales, narcotics and other illicit and immoral behaviors. The D.A.’s office was receiving a growing number of neighborhood complaints about rowdy behavior at the coffeehouse, and there were also rumors of drug sales there. Duggan resided on Bayard Street only a few blocks from Loaves and Fishes, and a sly politician with a fierce devotion to regulating community morals could hardly ignore such suspicious goings-on in his own backyard. Moreover, 1967 was an election year and Duggan was again running on a strong anti-vice message.

Duggan directed county detectives to put Loaves and Fishes under surveillance. After weeks of effort that included marijuana purchases outside the coffeehouse, eight officers swooped in on May 4 and arrested 30 people including Rev. Mowry; he was charged with keeping a disorderly house while the others were charged with disorderly conduct. Detectives found marijuana in the men’s room and assorted pills (later identified as amphetamines) in the pockets of two people.

Ironically, Rev. Mowry had met with about 35 nearby residents earlier that week to discuss solutions to noise problems; no one mentioned any concerns about marijuana. Mowry even proposed hiring an off-duty policeman to maintain order. No doubt the D.A.’s office was more interested in making a show of attacking the “drug crisis” for political benefit than addressing legitimate concerns about noise and raucous crowds.

A few days after the arrests, Duggan magnanimously withdrew all charges (except for those possessing amphetamines) in exchange for an agreement acknowledging his right to search the premises at any time and imposing several vague and impractical conditions on Loaves and Fishes like “frequently search for any narcotics brought in by patrons” and help “root out the trend toward crime and delinquency” in Shadyside. Blatantly ignoring Rev. Mowry’s recent efforts to accommodate the neighbors, the D.A. also demanded, almost as an afterthought, that the coffeehouse take steps to alleviate the noisy conditions.

At a subsequent press conference, Duggan bragged about the agreement he forced on the coffeehouse and condescendingly cast out insults, saying the area is becoming “a hangout for the maladjusted youth of western Pennsylvania” where drug use “is rising rapidly.” He described the Loaves and Fishes clientele as “dirty and filthy and dressed in the most peculiar clothes I ever saw” and suggested that “everyone should get together and rid the Shadyside neighborhood of these undesirables.” Clearly, the D.A.’s main objective was playing to public fears and prejudices in order to garner votes in the upcoming election.

Due to reams of negative publicity and Duggan’s incendiary comments, concern about the so-called “Loaves and Fishes problem” extended far beyond the few blocks surrounding Bellefonte Street. A vigorous Letters to the Editor debate broke out with commentary pouring in from throughout the region. Among the many screeds, a champion from the “pro” camp wondered why so much police attention was focused on a place “where Christianity is being practiced as a matter of policy” while representatives of the “con” side said the churches were pandering to “the worst element” and there was “moral rot here in the heart of Pittsburgh.” Opinion about the propriety of Loaves and Fishes was split about 50-50.

Incidentally, not one, but two letters pointed out all the lurid newspaper articles neglected to mention that a Methodist minister was providing an inspirational talk regarding “Who was Jesus Christ?” when the raid occurred.

Meanwhile, the Associated Press pounced on the story. Dozens of their member newspapers in at least 29 states gleefully published the tabloid-style account of the crackdown on the “haven for the rebellious beard-and-sandals set.” Editors nationwide conjured up scintillating headlines that combined three elements sure to raise eyebrows: churches, dope and cops (e.g., “Church-Run Beatnik Joint Raided by Narcotics Agents”).

Not to be outdone by the print media, WQED jumped into the fray by producing a one-hour special program allegedly to objectively study the controversy, but which unsurprisingly ended up provoking heated argument. Advocates for the coffeehouse went head to head with city and county public safety officials. D.A. Duggan played a major role.

The program (which aired three times) provided an excellent opportunity for him to shamelessly grandstand and present his law and order bona fides. Duggan knew the older generation of voters disapproved of the counterculture so he made sure they understood the D.A. was on their side. Duggan’s feelings were unequivocal: “You don’t see men with flowing hair, filthy clothes and no visible means of support hanging around such an area as this unless they’re maladjusted.”

In this climate of “straights” vs. “hippies,” upright Shadysiders lost no time in voicing their grievances. About 75 locals met with city and county representatives at nearby Liberty School to say what they now thought about the coffeehouse idea. The officials politely listened as the public let off steam, and did they ever, charging that unruly crowds “expect us to walk in the street,” “insult us when we come out of our houses,” “keep us awake with their noise,” “neck on our porch furniture,” and “lie all over our automobiles and lawns.”

Furthermore, they complained about garbage behind the building, bricks and beer bottles smashing their windows, and constantly cleaning beer cans off their lawns. Curiously, someone asserted that the outsiders were attacking people in Shadyside and “beating them up for fun.” A tenant from the apartments above Loaves and Fishes helpfully reminded everyone that the coffeehouse did not sell alcohol and the beer containers likely originated in Walnut Street bars.

Passions grudgingly cooled but soon there was more drama.

While county detectives were spotlighted for their vigorous clampdown on Loaves and Fishes, city police had surreptitiously been getting in on the act. For over six months, two Pittsburgh detectives posing as hippies had infiltrated the coffeehouse in order to gather evidence. Their disguises allowed them to gain the confidence of their suspects and buy marijuana from them on several occasions; a “bust” was finally made on July 11.

Although Rev. Mowry was incensed by their tactics, his protests fell on deaf ears as the police defended their methods. But if the authorities expected to be lauded for their work in battling the drug menace, their hopes were likely dashed after a photo of the “dope pushers” arrested at Loaves and Fishes did not resemble the public’s image of hardened criminals so much as frightened youngsters about to be scolded for some inappropriate hijinks. Even so, it was obvious that better public relations were necessary.

From then on, Mowry devoted considerable attention to forging bonds with community groups and public agencies. He spoke repeatedly in diverse settings ranging from churches and synagogues to YMCAs to Kiwanis Clubs. Mowry reached a wider audience via interviews on local radio stations. He talked mostly about the perspectives of young people who turn to drugs as a way of coping with alienation from society in general and their families in particular. These extended discussions of the problems afflicting local youth surely helped sway attitudes about the value of Loaves and Fishes.

Harassment from neighbors and overzealous law enforcement decreased considerably by late 1967. Aside from being called in to disperse a crowd surrounding a street fight outside Loaves and Fishes, there was no further police presence there. Duggan won re-election in November so he no longer had much to gain with the voters by prosecuting clergymen and teenagers. Loaves and Fishes could now do their work as intended and young people had a place to hang out without fear of repercussions. The nationwide notoriety generated by the Associated Press even attracted some celebrity attention: after her Pittsburgh concert in December, folksinger Joan Baez dropped by the coffeehouse to harangue that night’s crowd on the uselessness of a college education.

A November 1968 Pittsburgh Press story on local coffeehouses indicated the furor surrounding the Bellefonte Street version had subsided; the Press noted it was one of the “well-established” operations that “found the right approach to please their particular clientele.” In little more than a year, Loaves and Fishes was transformed from the reviled scourge of the community to a respectable neighborhood institution.

As Rev. Mowry spent more time networking, local theater personality Ted Scheuch was selected in 1969 to succeed the peripatetic Mowry as manager. Scheuch had previously managed two Pittsburgh coffeehouses and directed plays at Loaves and Fishes; he was also a lifelong counselor of drug addicts and other tortured souls. For all these reasons he was a natural for the position. Under Scheuch’s management, Loaves and Fishes continued its usual activities while adding one-on-one counseling for those in need of it.

Rev. Mowry’s interactions with Allegheny County human services agencies led to the realization that Loaves and Fishes could contribute considerably to drug rehabilitation needs through a more systematic approach that went beyond simply providing a place for young people to gather and talk informally. Mowry’s efforts culminated with the creation in 1970 of Whale’s Tale, an organization devoted to providing guidance for troubled youths. The first Whale’s Tale program was Karma House, dedicated to the growing problem of drug abuse. Soon a related activity called Amicus House was created to help runaways.

Loaves and Fishes quietly closed its doors in 1971. The coffeehouse was a noble experiment that had not fulfilled its potential and Whale’s Tale initiatives proved to be more effective for ministering to confused young people.

Whale’s Tale merged with the Parent and Child Guidance Center in 2001 to form Familylinks; the organization was enhanced by the addition of Vintage Center for Active Adults in 2015. Today, Familylinks, with headquarters in East Liberty and multiple regional facilities, provides a variety of behavioral health and other services to 11,000 people annually.

Undoubtedly Rev. Pierson and his colleagues never dreamed their modest effort to encourage young people to engage with their communities would ultimately become a substantial social services agency. A vote of thanks is overdue for their efforts and their willingness to endure the bumps in the road they encountered in the early days of Loaves and Fishes.