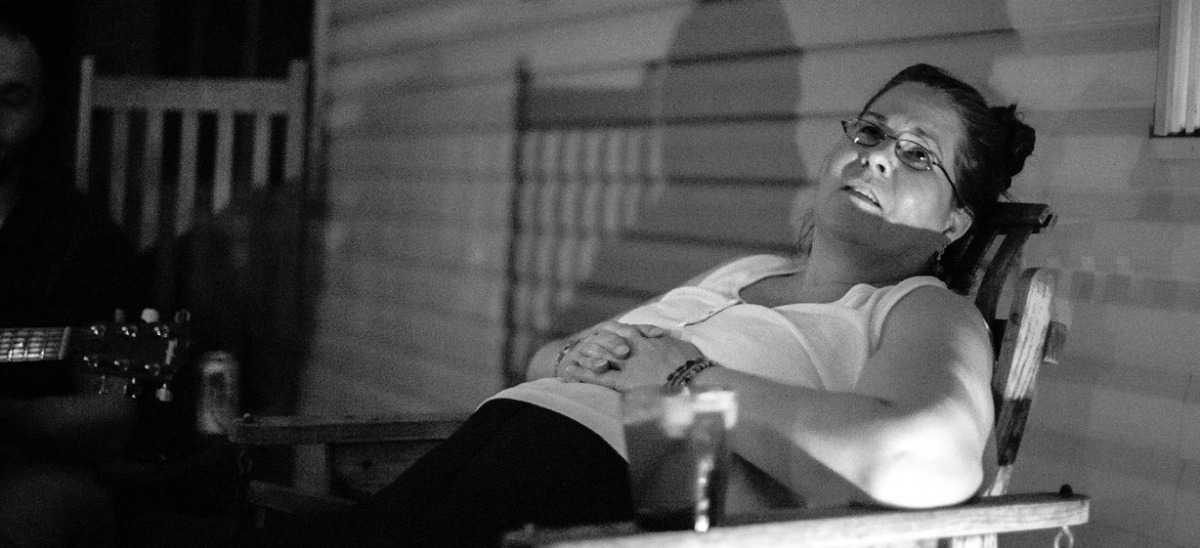

When I pulled up to Diana Staab’s house in May, it would mark my third interview with her and the second time that month that I would spend a few hours at her home in Level Green near Murrysville. When she opened the door and said hello, she was wearing a white T-shirt, black sweatpants and flip-flops, her brown hair tied back into braids and a short ponytail. She looked at me, then past me at the grass and trimmed hedges on her front yard.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”95″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

“You’re the insurance man?”

She had no idea who I was.

Diana suffers from a rare kind of amnesia, and since the night of Oct. 17, 2009, she has lost the ability to create new memories.

That Saturday night, Diana’s youngest son, Luke, left home around 8 p.m. to sleep at a friend’s house. He called his mother around 11 p.m. to let her know that he was safe and to say good night. When Luke got home the next afternoon, Diana lay on the floor of his bedroom, unconscious.

Luke, who was 14, called 9-1-1, and also called his dad, Dave Staab. Dave and Diana had separated five years earlier, but Dave lived just a few blocks away. Dave rushed home and rode behind the ambulance to Forbes Hospital emergency room.

Diana had a bruise on her head where she had fallen, so doctors initially suspected a hematoma—a blot clot that contributed to her passing out—and nothing more serious. But when she remained unconscious through Sunday, doctors began to worry. On Monday morning, she was flown to Allegheny General Hospital.

Doctors began to think she had contracted encephalitis—a swelling of the brain caused by a virus in the frontal and temporal lobes. Such an encephalitic attack strikes about 300 people per year in the U.S. Untreated, about 70 percent of those patients die, and survivors often have serious brain ailments.

It was 14 days before Diana woke up. The attack had shredded her memory. She had developed anterograde amnesia—the inability to create new, lasting memories. Similar to someone with early-stage dementia, her long-term memory is largely intact, while her short-term memory—her “remote storage,” as neuropsychologist Dr. Michael Franzen termed it—”is virtually nonexistent. You’ll speak to someone [with anterograde amnesia] and find that they remember the color of the dress they wore to the prom and the name of the person who sat next to them in the third grade, but they don’t remember what they ate for breakfast.”

Diana entered a rehabilitation center, designed to teach her skills that would help her live something approaching a normal life. Among other things, she learned to carry a journal with her at all times to write down the day’s events and remind her what she needed to do that day. After a month in rehab, she was back at home, and that’s when the real work began.

Prior to the incident, Diana had worked in the medical billing department of CVS Caremark. At different times, she’d also worked as a beautician, a house cleaner and a paralegal, in addition to working from home full time for a period when her four kids were young. Her itinerant work history made her ineligible for many disability programs, and her hospital stays were not fully covered by Caremark. Awash in hospital debt, her memory problems ruled out returning to work at CVS. Working alone as a house cleaner was largely out of the question because she couldn’t remember what she’d cleaned or why she was in an unfamiliar house.

Diana had been a talented cook, but amnesia made cooking virtually impossible, too. “Tuna salad is about as elaborate as she can get,” said her husband Dave not long after she awoke from her coma. “She just doesn’t remember what comes next.” And her impulse to cook—through long-term memories of bringing joy to people through food—made her potentially dangerous. She’d boil water for tea or pasta and forget to turn off the burners.

All of it put Diana and Dave in an awkward position. They were separated and living in separate homes, but Dave was really the only person who could take care of her. The kids were all in school—two in high school at the time, two in college—so without disability payments, they couldn’t afford round-the-clock care Diana needed. And while Dave had supported the family for decades as a salesman, he was unemployed when Diana’s amnesia struck. So he became her default caretaker, staying with her all day and sleeping over some nights.

Brain trauma tends to pull families apart, Dr. Franzen said. And amnesia patients often become depressed, as the people who initially offer help drop away.

“It’s real hard to care for someone in this kind of situation,” Dr. Franzen said. “This is such a stressful thing for families that there’s a high risk of it bringing divorce or a separation from kids and other family members. And, the person after the injury is not the person you married.”

Before Diana’s amnesia, the couple had separated three times, and Diana had filed divorce papers in 2000 before being talked out of it by her children and friends. As Dave said, “She was a very different person back then—very strong, knew exactly what she wanted.”

Ultimately, however, Diana’s circumstance reunited the family. In 2011, Dave sold the house he’d been living in and moved back home. After being told by Diana’s doctors that there was basically nothing she could do other than eat healthy and try to find some way to keep herself busy during the day, Dave researched alternative treatments, and they tried a few. But in the end, what probably helped Diana the most was simply Dave’s presence and the support of their children.

“I can’t imagine being in this house all alone, with my kids all gone and no one here,” Diana said. “I think our getting back together has been one of the good things.” And one of the rare memories Diana has been able to make since 2009 involves Dave. “I remember waking up in the hospital and telling him I loved him.”

* * *

Diana can’t remember her dreams, what she ate for breakfast, or what people’s faces look like. She retains memories as long as seven minutes before they’re gone. But she can recall, for much longer, certain moments that instilled her with some form of passion. Dr. Franzen calls these “emotional memories”—memories that typically stem from instances of intense joy or sadness or anger. Diana remembers Dave at her hospital bedside in 2009. She remembers holding a baby at a wedding in April, an incident she recalls over and over again. She even remembers cleaning one of her daughters’ apartments in June, “because it was for one of my kids—and it was really messy,” she said with a smile.

But there’s a darker side to emotional memory as well. Diana hangs on to grudges. “I mull over things that anger me,” she said. Repeatedly, she brings up a dispute from 2013 over losing a house-cleaning job. If someone says something to her that she doesn’t like, it nags at her in a way that can take over entire days of her life. She’ll think about the thing that bothered her, forget that she thought about it, and then rethink it over and over. Dave and their daughter, 27-year-old Maranie, call these her “bad days.”

Four days per week, a caretaker takes her to the local YMCA for aerobics classes and accompanies her to clean houses when a friend or acquaintance needs work to be done. On those days, Diana is active, with things on her mind. However, when she has nothing to do, “she’s got time to ruminate,” as Dave said—to stew and seethe about the negative emotional memories she sometimes harbors. So Dave and the family try to keep her busy.

Everyone in the Staab family leans toward artistic pursuits. Maranie works in sales for Xerox, but is also a photographer with an impressive portfolio. Dave is a musician and a skilled artist who now specializes in faux painting that can make living rooms in the East Hills look like Tuscan villas. Maranie’s 26-year-old sister, Kristen, works in marketing, but is a talented painter with a fine art degree from Carnegie Mellon University. Diana is artistic, too. For years, she’s made jewelry using beads she gets online and from local shops.

The ornate and beautiful jewelry looks nearly identical to items for sale at Monroeville Mall for hundreds of dollars. An entire room in their home is devoted to beading, with a desk covered in partially organized boxes filled with beads and completed bracelets, necklaces and earrings. For years after she was stricken in 2009, Diana barely entered that room. Then one day, she recalled, “the beads started talking to me again,” and she resumed making jewelry. Now, the beads “talk to her” almost daily, and she makes jewelry for friends and family. “I don’t need to be paid,” she said. “It’s just something to keep me busy and happy.”

The two most prominent cases of encephalitic amnesia in popular culture in the last decade were profiled in The New Yorker magazine. Both involved artists—a New Jersey-based illustrator, Lonni Sue Johnson, who drew for major magazines including The New Yorker; and Clive Wearing, an English musician and musicologist. Like Diana, both were able to find solace through art after amnesiac attacks.

Diana’s memory loss is not as severe as Johnson’s or Wearing’s (both Johnson and Wearing lost archival memories as well as the ability to form new memories), and outside her circle of friends and family, Diana’s case is largely unknown. No medical journal articles have been written about her. And while Dr. Franzen describes her memory loss as being “rare” and “extreme,” Diana hasn’t had a neuropsychiatric evaluation—an official test at Allegheny General to determine how well her brain is functioning —since December 2011. It’s up to her and her family, in other words, to try to make progress. In many ways, they’ve done so. Diana can cook popcorn now—on the stove. She can clean houses with her caretaker. She can carry on conversations. She can talk with friends and go on road trips with her family.

You might have a conversation with Diana and not even notice she’s an amnesiac. Only through longer conversations would you realize that she’d told a story minutes ago and then repeated it almost verbatim. On her front porch in June, she repeated the same story three times about what it was like to work at CVS Caremark.

She still keeps a journal to remind her about the events that happen in her life. To date, Diana has filled five journals, all of them nearly two inches thick, with her longhand cursive writing recording snippets of her life. She is working on a sixth. In June, she read aloud from an entry she wrote in August 2014:

Gotta get some money out of the bank.

Linda called. She was running errands.

Made chocolate chip cookie dough.

Ate a salad earlier. Dave brought home pizza at 9:35, had two pieces.

Went to Dom’s for a fish sandwich.

After reading it, she said, “There’s no memories here. It’s like reading a book for the first time. I live it. I write it. I did it. But I don’t remember it.

“I miss planning for things. I miss being able to look forward to things. I miss remembering what happens to me. And most of all, I miss who I was.

“That’s the hardest part—trying to be who I was before all of this happened. And then having to remind myself that I can’t be who I was—that I’m someone different now. The old me is gone. That’s hard for me to handle. It really is.”