Kathleen “kit” McCafferty, a victim of childhood sexual abuse, has never discussed her trauma with anyone, and its residual rage and pain have left her estranged from her shell-shocked husband and grown children. Now approaching death, Kit is determined to complete and bequeath to her family a series of confessional notebooks, in order to break the intergenerational chain of fear, grief and alienation.

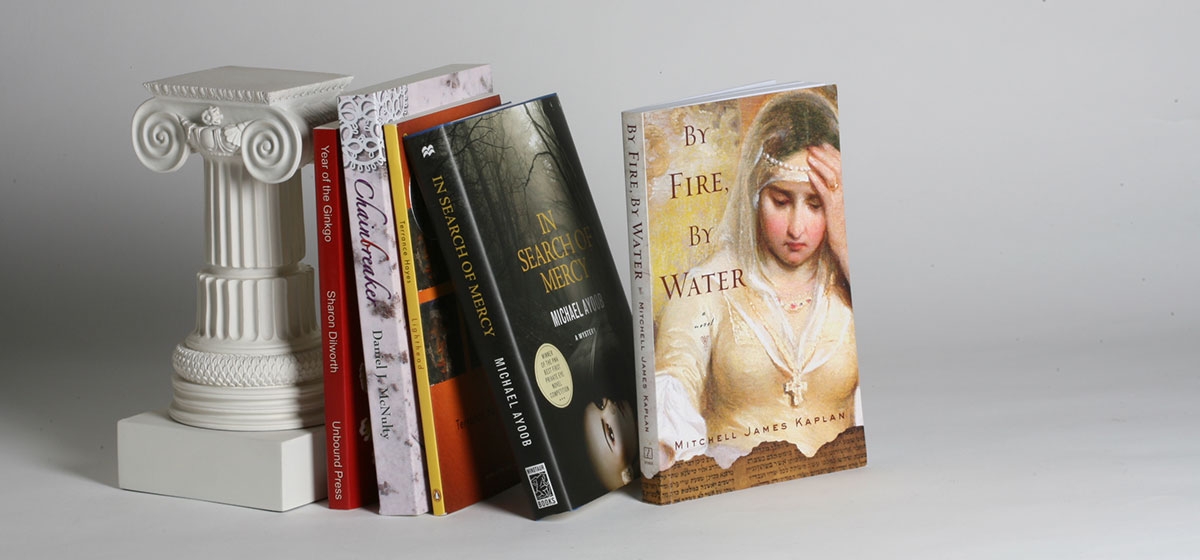

“Chainbreaker,” by local lawyer Daniel J. McNulty, recalls Reynolds Price’s 1986 novel, “Kate Vaiden.” Both books feature middle-aged women re-evaluating their relationships after a cancer diagnosis, recounted in the first person by male authors. But whereas Price’s transgender narrative felt excruciatingly affected, first-time novelist McNulty’s feminine voice is remarkably believable, both as a confused but hopeful teen and as an older woman consumed by regret. If the writing occasionally seems stilted, it only serves to underscore the difficulty Kit has in confronting her demons and expressing her despair.

Indeed, the simplicity of the story and its amateurish tone belie a well-developed subtext involving religious notions of sin, guilt, suffering, forgiveness and redemption. Kit’s Irish Catholic mother, who in memory seems only to cower and pray, is named for the martyr Agnes, meaning “lamb” (as in Agnus Dei, or Lamb of God). Kit’s long-suffering, infinitely accepting and unconditionally loving husband is named Paul, after the apostle who modeled his life on Jesus Christ. Their son is described as “a savior rejected,” and Kit speaks of the “altar of blame” dedicated to her tyrannical, sick-bastard father, who, in a nice touch, is named Seamus (shame-us).

Kit’s emotional pain and isolation are so great that cancer, when it appears, seems like no big deal; merely a physical manifestation of her psychological suffering. In fact, the disease functions as a blessing of sorts, allowing for surgical removal of the breasts and reproductive organs that had long served as sources of self-loathing, and reuniting her with loved ones she had previously pushed away. When the cancer spreads to her brain, Kit is visited by visions of ancestors and angels that help her to open up and let go. Facing the end, with nothing left to fight or fear, she finally confronts “It,” the unspeakable, defining experience of her life.

An auspicious debut novel, “Chainbreaker” provides moving insight into the psychology of abused children and the adults they become, as well as a message of hope for damaged souls of all sorts.

By Fire, By Water

by Mitchell James Kaplan

Other Press ($15.95)

Confession and Catholicism also feature prominently in Mt. Lebanon resident Mitchell James Kaplan’s ambitious novel of the Spanish Inquisition, “By Fire, By Water.”

The action centers on an actual historical figure, Luis de Santangel, the Spanish courtier who convinced Ferdinand and Isabella to send Christopher Columbus on his westward voyage to the Indies, and the financier behind that expedition.

Santangel and his family were marranos, or New Christians, who converted from Judaism in order to retain their property and achieve a measure of social mobility. In 1481, when Kaplan’s story begins, Santangel is a rich man who has risen to the rank of royal chancellor of Aragon. He is so sure of himself and his position that he dares to fraternize with select Jews, dining discreetly in their homes and participating in covert discussions of the Torah. Because his activity is motivated by intellectual curiosity rather than worship, he fails to perceive it as judaizing, a form of religious recidivism that is the precise target of the Inquisition.

Santangel soon finds himself a party to murder and dancing as fast as he can to prevent exposure, ruin or execution. Along the way, he engages in a love affair with a proud Jewish silversmith from Granada who demonstrates considerably greater strength of character than her paramour.

Santangel survives, of course, but at the cost of his family. His only son turns against him to become a servant of the repressive Church, and his brother, Estefan, is burned alive in the ritual of the infamous auto-de-fe. The most powerful scene in the book occurs when, in the course of four pages and the exchange of a few snide remarks, Estefan Santangel goes from being a big shot having a bad day to a heretic on his way to rack.

“By Fire, By Water” contains many well-crafted phrases and much interesting information, but its greatest merit is in demonstrating parallels between a notorious period in human history and disturbing developments in modern life. Witness, for instance, an insistence on religious orthodoxy for the purposes of political control; a religious climate dominated by fanaticism; the unrestrained use of rumors and innuendo to sway popular opinion; and the manipulation of the masses through the indulgence of base appetites. One wants to feel hopeful when, at the end of the book, Columbus discovers the New World, but the image that remains is of history repeating itself in some very unsettling ways.

In Search of Mercy: A Mystery

by Michael Ayoob

Minotaur Books ($24.99)

Dexter Bolzjak has two dead-end jobs; one sorting produce in The Strip, and the other suppressing memories of the brutal abduction he endured eight years earlier. Though still in his twenties, he is a full-fledged, strung-out loser, subsisting on cigarettes, fast food and the pills he steals from his best friend’s mother, whose gloomy basement he inhabits. When he is approached one day by a mysterious and apparently deranged stranger seeking a lost love, Dexter accepts a $100 retainer and the promise of a drawerful of cash to set out in search of Mercy Carnahan, the reclusive old-time movie siren who was once plain Agnes Zagbroski of Pittsburgh.

“In Search of Mercy” was awarded the PWA prize for Best First Private Eye Novel in late 2010, and deservedly so. As a private eye, Dexter is no great shakes, but the book’s neo-noir elements are exceptional. Author Michael Ayoob’s homage to the graphic violence of classic hard-boiled detective fiction, as well as the “weird menace” of mid-century pulp fiction, is polished and pitch-perfect.

Equally accomplished is the structure of the novel, which upsets the expectations of habitual mystery readers. Apart from Dexter’s own abuse, no crime occurs, and Mercy herself proves pretty easy to find. (The “mercy” that eludes Dexter is relief from the visions that haunt him.) The “mystery” of the subtitle lies in determining what is genuine, and as the story ends, the reader begins to doubt his own ability to distinguish between reality and fantasy.

Furthermore, the author does a terrific job exploring themes of violence and voyeurism, both public and private; expertly describing the frenzy and communal bloodlust of ice hockey fans and greyhound-wagerers, as well as the creepy peeping and professional sadism of Dexter’s roommate.

Ayoob, a Lawrenceville native who recently returned to Pittsburgh from New York, puts a lot of effort into his descriptions of local neighborhoods, but that is the least of the many reasons to read his fine work.

Year of the Ginkgo

by Sharon Dilworth

Unbound Press ($15.95)

If you prefer your fiction free of psychosexual and sadistic excesses, Sharon Dilworth delivers it in a light and breezy roman a clef titled “Year of the Ginkgo.”

The protagonist, Caroline, is a bored, middle-aged matron fraught with delusions. Having recently lost her job with the City of Pittsburgh, Caroline now works full-time at the “profession of fabrication.” Largely ignoring her family, she fixates on their neighbors, whom she envisions as minor characters in her imaginary romance with the sexy Scotsman down the street. She eventually discovers, however, that some people have real problems, and it is she herself who plays a supporting role in a disquieting drama unfolding close to home.

If Caroline spent less time online, looking into ginkgo trees and all things Scottish (and more time reading literature by local authors!), she would have been a lot quicker to pick up on the secrets lurking behind the facades of Shadyside’s handsome homes. Instead, she stubbornly remains in a fantasy world until the needs of the Chinese orphan, Lily, bring her back down to earth. Their relationship, like the ginkgo of the title (also of Chinese origin), sprouts in response to disturbances in the local environment.

Despite the crisis at the book’s core, its tone is chatty and confidential in a Bridget-Jonesy, Dear-Diary sort of way, and the storyline is punctuated with some fine comedic touches. There is the teenager who spends her summer up a tree protesting global stupidity; a neurotic friend who circulates photos of her younger, slimmer self at parties; an adolescent Caroline eavesdropping on a party line. Most amusing of all is the image of mature Caroline, thoroughly self-absorbed, pausing periodically to wonder about her mental health, but never pondering the implications of the murder mystery her husband is writing, in which the only possible suspect is the dead woman’s spouse.

With its combination of menopausal angst, daydreaming and tittle-tattle, “Year of the Ginkgo” definitely qualifies as chick-lit. As such, it is best enjoyed with a glass of white zinfandel, which it closely resembles: crisp, undemanding and unpretentious. What’s not to like?

Lighthead

poems by Terrance Hayes

Penguin Poets ($18.00)

Congratulations to Terrance Hayes, professor of creative writing at Carnegie Mellon University, who recently won the National Book Award for Poetry.

“Lighthead,” Hayes’s fourth collection, includes several inventive works constructed in the popular presentation format known as pecha kucha. This methodology, involving 20 images described in 20 seconds each, was originally developed by architects in Japan to showcase design ideas, and has since spread to the business world. Hayes has further adapted it for his own purposes, eliminating the visuals to illustrate his point, “Not what you see, but what you perceive: that’s poetry.”