Lessons from Last Place

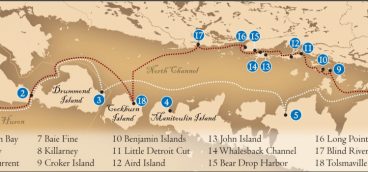

Sailing is a big part of the culture in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where I’ve spent 63 straight summers. And some might say that from an early age, I earned the dubious distinction of being a kind of “Jonah” of sailboat races. I’ve never seen myself as that ill-fated shipmate of yore, but the case could be made.

My first race was as a toddler in one of the 290-mile Port Huron to Mackinac Races my Dad skippered. Why my parents took a 1-year-old on that race is something I can no longer ask them. But apparently it was a mistake because, as I crawled around in the cockpit (wearing a tiny life jacket?), I allegedly turned the ignition key to “on.” That drained the battery, so that when we were later becalmed for a day and Dad decided to drop out of the race and motor into port, the engine was dead. Perhaps that should have been an omen.

As a little kid and the youngest by a wide margin, I’d peer at the eye-level card table where my parents and siblings played a Parker Brothers board game. Not Monopoly, though. They played “Yacht Race: The game of sailing and racing strategy.” Everyone got a colorful sailboat piece, 12 “Wind Change” cards and three “Spinnaker” cards to accelerate their speed. Dad explained the terms to me: halyard (the cable that hauls the sails), port and starboard (left and right), bow and stern (front and back), and blanketed (when someone steals your wind).

I crewed in local races, an agile, young foredeck hand, either with Dad or one of his friends. Dad was an even-tempered skipper, but after a while I chafed under his familiar authority, preferring other skippers because they’d be on their best behavior with unrelated crew. And if they lost their tempers, which some did, it had no consequences, aside from realizing they were jerks. Skippers all had their quirks. One cursed in German. Another had a memorable trick finger and cursed when it got stuck.

Once known as “Sailbad the Sinner,” Ensign number 24 is the oldest in the Les Cheneaux Islands.

I was 11 when I skippered my first regatta. I sailed my aunt’s Sunfish, a fiberglass boat of about 100 pounds, just under 14 feet long with broad green and white stripes on its triangular sail. Sunfish are great little boats, and I knew how to handle it well. Aunt Dori was happy it was getting used, and I sailed out to the race with high hopes and great expectations. How could I know that my first three-day Sunfish regatta would launch a 50-year lesson on humility and perseverance?

In each of the three races, I got a good start, but by the end, one by one, every boat passed me. Littler kids. Overweight people. Girls. Everyone. I later examined the boat and found screws on the deck where you could tilt the boat on its side in the sand and let water out of the hull. And before the next season’s regatta began, I emptied the water, cleaned and waxed the bottom and even sanded the front and back edges of the wooden center board and tiller to reduce drag. No matter. Race after race, year after year, I’d get a good start and slowly but surely fade to the back of the pack.

It was embarrassing, especially as a teenager trying to impress girls. Being seen as a good sailor, which I thought I was, might have been a decisive boost instead of an obstacle: “He seems nice, but why does he always lose?” And each year the club gave out the “Most Improved Sailor” award and various trophies. Each season, I imagined winning one but never did. But beyond embarrassment, I just didn’t understand what I was doing wrong.

Losing wasn’t entirely negative, though. It gave me my first experience with the justice system. One year, yet another young rival came along and took his turn at winning. But after a race on a light-wind day, two kids accused him of sculling, which means moving the tiller (and therefore the rudder) back and forth and propelling the boat rather than sailing it to victory. A tribunal formed, and I can still feel the weight of accusation. As much as I would have loved to have one of the many who beat me be disqualified, I reported that I saw him slowly move his tiller back and forth — I can still see it in my mind’s eye — but that it wasn’t vigorous enough to propel the boat. He wasn’t disqualified and we’ve been friends for 50 years.

I didn’t want to hurt my aunt’s feelings, but I’d long suspected some unseen problem with her boat. So when I was 17 and my friend Anne offered her boat, I jumped at the chance. Eureka! In three races, I got a third and two seconds. Later, I compared the weight of her boat with my aunt’s, and clearly the family Sunfish had some kind of leaking seam which waterlogged it almost immediately. I never raced a Sunfish again, but at least that curse was lifted.

***

In those years, the Sunfish fleet was for kids, and so, armed with my recent success with Anne’s boat, I decided I was ready to move up to the big leagues. That meant sailing the Ensign.

The Pearson Ensign is a 22.5-foot, 3,000-pound fiberglass sloop. Thanks to Dad, our Les Cheneaux Islands have the biggest fleet in the country, about 70 at last count. Though we lived in Cincinnati in the winter, Dad had a sideline business selling sailboats in Cleveland. He was a Pearson dealer, and each summer from the mid-Sixties through the late Seventies, he brought up a new, brightly colored Ensign, which we sailed until he sold it to a friend. He probably sold 30 Ensigns up there, and the fleet then gained its own momentum. When you have that many sailors with the same boat, it makes for terrific racing — no handicaps needed. And in those early years, Dad raced and brought home silver cups which still line the mantle of our cottage.

In the late Seventies, he brought up a boat for us to keep. But it wasn’t a new one. It was Ensign number 24, made back in 1962, the first production year and the same year I entered the world. Over the next 21 years, Pearson made 1,775 boats, each with the production number on its mainsail. So number 24 is one of the oldest still sailing. It was named “Sailbad the Sinner,” which Mom didn’t like so we changed it to “White Loon” after a local Indian chief.

By the summer of ’80, I was 18 and I’d sailed it a lot. I asked Dad if I could skipper the three-day regatta and got the go-ahead. I don’t recall who crewed with me — probably two friends — but once again, my high hopes collided with reality. In the first two days, I was last both days, and Dad passed along one of his most memorable aphorisms: “If you find yourself in last place, do something different, even if it’s wrong.”

So on the final day, I did something different. I feigned illness.

Dad took over, and my older brother sailed with him along with a third crewman. A prominent attorney from Pittsburgh had won each of the first two days and only had to place fifth to win the regatta. Dad took a tack far from the fleet and when he tacked back, the strategy had lifted him to first place and on a collision course with the Pittsburgh boat.

It was a heavy wind that day with three-foot waves in the bay, which was unusual. Dad had the right-of-way, and called out “Starboard tack!” in the high winds. Both boats were heeled way over, and by the time the other skipper realized he couldn’t pass in front of Dad and had to duck behind him, it was too late. He later told Dad that a crewman couldn’t loosen their big headsail to flatten the boat, and with the boat heeled over so far, the tiller wouldn’t answer.

They T-boned our boat with a crash I heard across the bay. Their boat scraped over the gunwale several feet into our cockpit, and with our boat heeled over as well, our mast pointed right at their boat instead of straight up. The riggings of both boats tangled, with the strain building until our 32-foot mast snapped and fell into our cockpit. To avoid it, my older brother, 23 at the time, jumped overboard. Fully clothed in those three-footers, he was luckily fished out by a nearby power boat.

If there’s been a worse racing collision in the islands since then, I’m not aware of it. The upshot was that the other skipper bought us a new mast and he and his family were the only friends I knew when five years later I fatefully moved to Pittsburgh.

***

Racing isn’t for everyone. Even without a collision or dismasting, racing is nothing if not intense. It’s the last thing many sailors want. A nice afternoon sail is peaceful and calm. You choose when to go out — generally a beautiful day, with a favorable breeze, refreshments and friends. It’s quiet and peaceful. You go wherever the wind blows. You leave the world behind.

Not so with racing. If it’s hot with barely a breath of air, you slather on the sunscreen, sweat and remain largely motionless for fear of disturbing the slight headway the boat’s making. In heavy wind and rain, you don yellow rain gear, hats and life jackets and battle the sails until your hands cramp and your muscles are tight as steel bands.

It’s all about performance. Even on calm days, you’re constantly scanning the wind, water and other boats and adjusting the sails, settings and weight. Mistakes lose races.

And for adrenaline, there’s nothing like the start of a sailboat race. I played high school basketball, college football and had a tryout with the Pirates, but to me, the start of a sailing race is the most fascinating spectacle in sports. Nothing matches the intensity of the starting line.

Two hours before a race, I notice a pit in my stomach. By then, you’ve prepared the boat and your mind plays through possible starting scenarios. An hour before the start, the race committee lays out the course at the skipper’s meeting. Then everyone hurries out to their boats and raises their sails, slapping and cracking in the wind, as the mechanical winches tighten them — click, click, click click! Then it’s time to unmoor and sail to the line, see which end is favored, and go over the plan with the crew.

At six minutes, you synchronize the stopwatch with the six-minute horn. And then, the period from six minutes until one minute before the start is like the eye of a hurricane. The boats sail around, seemingly blithely.

At one minute, it all changes. Sails get pulled in or “hardened up” and everyone heads for the line.

At 30 seconds it’s bedlam. Imagine the Kentucky Derby, but instead of being locked in the starting gate, 15 horses run toward the line, heading diagonally across one another amid plunging waves, and shouting as they converge. The stronger the breeze, the louder the cries of “Starboard!” “You’re barging!” “Head up!” One person’s mistake dashes another’s careful plans.

When the starting horn blares, winches clatter for a moment, and then it’s quiet, as the crews hike over the rail on the high sides and all eyes look ahead for clear air and an unimpeded path to the first upwind mark.

***

Dad passed away in 1993, and the boat wasn’t far behind him. During one very high-wind race, one of the metal stays (wires) that keep the mast erect ripped out of the spongy deck.

By that time, my three kids were little, and I raced only sporadically. The results showed. Racing had become something I didn’t enjoy but felt obliged to do.

I was at a crossroads. It would be easy to just fade away, dump the stress and consign racing to the past. I could just drop out and never do it again; plenty of people did that. They liked sailing but not racing. But if I stopped, that would mean the know-how would pass out of our family. Imperfect as I was, I was the only one in the extended family who had skills enough to enter the fray. If I stopped, racing would be something other people did. Not our family. And so, I finally decided to get back into racing, come what may.

I discussed it with my mother, and before she died in 1998, she hired the local marina to completely overhaul old number 24. It was the first time they’d undertaken what is now a routine procedure, and the result was magnificent. That and a new set of sails gave the boat a new life and me the opportunity to rededicate myself to the sport.

Since then, I’ve raced more often. And the more I raced, the more nuances I’ve learned in terms of rules, rigging, tactics and strategy. The best I ever did was on a strong wind day. I ripped across the starting line at full speed with fresh air ahead, and by the end, I came in second to “Beelzebub,” an aptly named nemesis. Still, it was a major victory in what has become an extremely competitive fleet — more competitive than when Dad raced. Some of the best sailors are college professors who have summers off, and just about all of the sailors spend more time racing than I do. I came to realize that luck plays a very small role. You finish where you deserve to finish, which for me has been the lower middle of the pack.

So it was until a few years ago, when I decided to see, even at 60, if I couldn’t improve a little more. So I got new sails and started reading. I considered going to a clinic the yacht club held. Was I too old to seek help? I decided the answer was no. So for two years in a row, I spent an afternoon with the best racer around — Tom LaBelle — the Ensign national champion three times over. He couldn’t have been more gracious, and I learned that all these years I was doing two things wrong that made me uncompetitive downwind. (It’s a secret).

***

Last summer I once again entered the regatta with high hopes. On the previous Saturday, I’d gotten a third and a second in the races with 10 other boats in the non-spinnaker division. It was the best I’d ever done. But just as in previous years, my regatta hopes were dashed in the first two days by bad starts. Lower middle of the pack again. But this time, for the final race on the third day, I didn’t feign illness.

My son Sam and his wife Kate crewed, and in the minutes before the start, there was so little wind that we dared not stray far from the line. Three minutes. Then two minutes. At 90 seconds, we headed closer to the line, barely moving in that light wind. Just then a freakish thing happened. A big cruiser drove by sending three-foot waves into the fleet. All 10 boats simply bounced up and down. Sam grabbed the boom so it wouldn’t heave violently. (Here’s my only sailing joke: I never understood why they called it the boom, and then it hit me.) The waves killed every boat’s speed and momentum, and when the pandemonium subsided, we all started back to the line. 20 seconds. 15. 10. Then a spot opened in the most favored position. No one was heading into it, so we did, crossing the line first in the most desirable spot.

The race was on. A sudden, unusual wind shift meant we didn’t even have to tack to the first mark. We simply headed straight for it, getting a fresh and favorable breeze. We rounded the first mark ahead by six boat lengths, letting the sails out as we turned down wind.

The trouble with being in first place, I suddenly realized, was that I wasn’t exactly sure which of the two possible downwind marks I was supposed to go around. I was used to following other boats and with the whole fleet now behind us, there was no one to follow. I joked briefly and altered course, hedging my bets as I watched where Beelzebub, the second-place boat was heading and losing some ground in the process. I figured out the mark, but the wind shifted dramatically yet again, and suddenly what was a downwind mark was upwind.

Beelzebub was now behind us on the same course — but not gaining — and the rest were much farther behind. Beelzebub suddenly tacked to port (left), and when you’re in first, the common practice is to follow suit, taking the same tack, “covering” the boat behind you, so they can’t gain appreciably.

But I decided to test the wind a little before covering him, and lo and behold, it shifted slightly again, giving us a major advantage on our tack and ultimately pushing Beelzebub way back. We were benefiting from the advantage that leading boats get — fresh, strong wind that hasn’t been bent, twisted and weakened by going through and around other sails.

We rounded that upwind mark way ahead of the field and then headed toward the downwind mark, leading the next closest boat by maybe 15 boat lengths and the others by much farther. We kept our weight forward and adjusted our sails as needed, watching what the boats behind us were doing.

A new second-place boat was gaining on us, and the sound of his bow wave was menacing in my ears as he neared. At that rate, it seemed they might well catch us, especially if the finish line were a half mile away.

But the line wasn’t half a mile away — just 10 boat lengths, 9, 8, 7 and as we crossed the finish line, the committee boat blew its horn and a nearby power boat cheered. In the cockpit, Sam, Kate and I let out a whoop and had a group hug.

After 50 years, I had finally won a race.