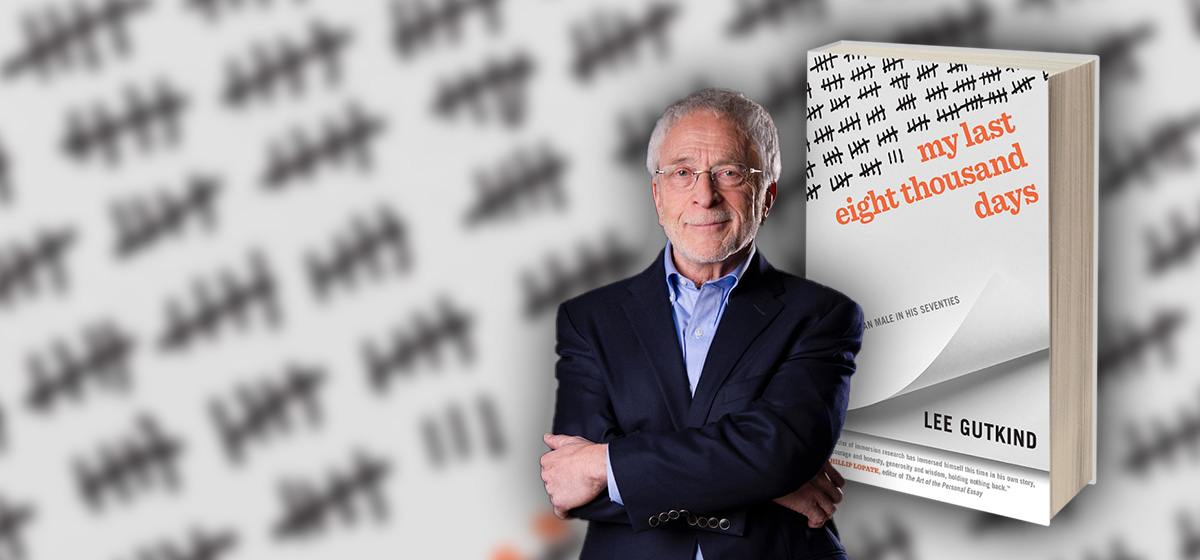

Lee Gutkind on Writing His Memoir, “My Last Eight Thousand Days”

My memoir, “My Last Eight Thousand Days,” published in October 2020, had been a work in progress for at least 10 years—just as my life had been a work in progress for 70-plus.

I think of the book and the process of writing it, digging deeply into my life, as a bridge from the Lee I used to be to the Lee I am now—transformed. Writing the book helped me analyze my life and adjust to a more satisfying and realistic future.

“My Last Eight Thousand Days” is about aging, obviously—a subject and a reality that I had aggressively avoided for my entire life until my 70th year, when my two best friends died, and my mom, my boon companion, passed away five days before my 70th birthday. Along with these and other personal losses, a book that I had hoped would be the triumph of my literary career, and had felt intimately connected to, fell apart. That year leading up to my 70th birthday was filled with tragedy and loss. I felt trapped and blocked.

As a writer, I spend a lot of time by myself, at home with my notebook, display and keyboard. Not getting out too much or working too hard to establish a life away from my work. Almost all of my books have been what might be called “immersions.” I devote lots of time—years!—investing myself in the lives of others—organ transplant surgeons, roboticists, baseball umpires and more—trying to understand and recreate the characters about whom I am writing, seeing the world, their challenges and passions, through their eyes. But doing that conscientiously and obsessively for so many years made it easy to ignore my own circumstances. I’m not saying that I have been all alone, but my work has been my all-consuming priority. I didn’t need or want much else until my 70th year. Losing my friends, my mom, my book—my support system—forced me to realize that there was something more to life than my work and that some sort of change must occur.

One change was writing something different—getting out of my well-established bailiwick. All my life I have been writing about other people, being a chameleon in various and seemingly exotic worlds. It was time, I decided, to turn the lens of my mind around and do a deep dive into myself. It wasn’t easy to make that transition. I had a lot to learn not only about writing in this new way, but about myself and what made me who I am. The process is not unlike devoting a half-dozen years to therapy. You sit in an office, prompted and encouraged by a nod of a therapist’s head, while he or she makes encouraging “hmmmm” sounds, and you spill out your stories and anxieties. And then, until the following meeting, you think about and ponder the memories and ideas you shared, and when you next sit down on the couch, you often tell the story a bit differently, sometimes changing the entire narrative and making contrasting conclusions. That’s part of the process of writing a memoir. It is not a one-shot deal; it’s more like a shotgun. Memories are scattered, revision after revision, tangent after tangent, with the pain and confusion that go with it. And you never know, draft after draft, until months or years later that you’ve got it right, if you ever know it at all.

And this other thing: You are not just writing about yourself in a memoir. You are writing about the people in your life, many of whom are most dear to you. What will they think, you wonder? Will family members object to the way I’ve described and judged them, or disagree with the way I remember incidents? Maybe some will think less of me based on the stories and the truths I tell. Or maybe they’ll question or criticize my decisions—how I behaved, how I parented, how I brought problems on myself. This can be frustrating and downright embarrassing. And what about those people who don’t know me? I am undressing, outing myself, turning myself inside out, for strangers.

So why did I write this memoir? First, because of the challenge and the need for self-understanding. And second, and more important, for my readers who have gone through similar traumatic experiences and are edging up on 60 or 70 or 80 and finding it difficult to accept and adjust. Not just within themselves, but perhaps more so because of society’s perception of aging. The myth that older age makes our minds muddy, just because we may be moving more slowly than we once were, that we are suddenly unable to work, to be productive, to contribute to society. That we are somehow and for some reason expected to play golf, to retire, sit in the sun, smell the roses, and gradually fade away.

But look: Here I am having just written a new book—a ten-year odyssey into myself. And teaching full time at a large university. And leading a literary foundation, editing a magazine. I have made many new friends and reconnected with old ones because of what I have learned by writing my book. Old age won’t keep me down, slow me down or frighten me any longer. In fact, I am going faster now, but in a balanced way, because, after all, I only have a portion of my eight thousand days, more or less, to live. Or maybe, if I am lucky, even longer. And I want to take advantage of every last one of them. Eight thousand is only a number, after all—just like turning 70.