Kinetic Theatre’s “Embers” Tells All

That Kinetic Theatre Company’s “Embers” is such a moving play should be counterintuitive: it violates one of the most basic rules of art, “show don’t tell.” This is a work that shows nothing and tells everything, which is doubly ironic, as its principal character, who does most of the telling, does not trust language. Based on the 1942 novel by the Hungarian writer Sándor Márai, and adapted into a play in 2006 by Christopher Hampton, it still exudes its bookish patina, like a Stefan Zweig story performed on the stage. And like a Zweig story, it’s ethereal, philosophical, and melancholy, adjectives more commonly associated with fiction than drama. But as drama it’s extremely effective, even if it has less action than “Waiting for Godot.” And this is because the acting is so strong.

Without giving too much away, the plot is simple: two old childhood friends reunite after 41 years, on the eve of World War II, in an ancient Hungarian castle where one of them, Henrik (Sam Tsoutsouvas) has lived all his life — a fading aristocrat who might have stepped out of Zweig’s novel “The World of Yesterday.” He still primps around admiring his former military uniform, and playing with his old pistol, like a boy who never had enough toys – or friends – in a sad, lonely, dream state. Attended by his aged nanny, Nini (Susie McGregor-Laine), he’s a kind of male Miss Havisham, reliving the day his best friend Konrad (Jack Wetherall) left him those four decades ago, after what he suspects – we come to find out – was an affair with his wife, who died only a few years later. And there are even darker aspersions, which I won’t elucidate. Thus, the action – as acutely directed by Andrew Paul — is mostly cerebral, and becomes a cat-and-mouse game of accusation and hopefully, for Henrik’s peace of mind, confession. But Konrad is not so easily lured into such a trap. And that is what makes this show so intriguing.

As Henrik, Mr. Tsoutsouvas places his words like pieces on a chessboard in a scrupulous manner. He’s as meticulous in how he expresses himself as a man who’s been practicing the same speech all his life, but he takes tantric pleasure in not giving away exactly what he’s trying to say. In fact, this might be the most tantric play you’ll ever see, especially between two men. Henrik converses like someone who has read too much Nietzsche and shares his distrust of spoken language, as when Nietzsche famously wrote, “There is always a kind of contempt in the act of speaking.” Henrik’s sentences come out not like social discourse, but more often as philosophical pronouncements; for example, “Passion is not amenable to reason and eventually it has to find some way of expressing itself. Every great passion is hopeless, of course, otherwise it wouldn’t be a passion, it would just be a lukewarm inclination or a clever calculation.” He is not one for small talk.

As a result of his novelistic origin, Henrik has a tremendous amount of dialogue, yet Mr. Tsoutsouvas makes each sentence a creative act, not a regurgitated one; thus, there is a freshness in the delivery of even his longest speeches, what we would call monologues in Shakespeare.

Mr. Wetherall, as Konrad, has the difficult task of listening to his friend try to interrogate him, without giving anything away, while simultaneously looking like he’s not trying to be evasive. There are pregnant moments when he appears disembodied as he perceives and reacts, like a Picasso-esque face fractured into several disparate emotions. It’s a brilliant give-and-take, and if you appreciate such rarefied acting, you’ll love this production.

Ms. McGregor-Laine has the briefest stage time as the nonagenarian Nini, but establishes her presence just as deeply as the other actors. In a Proustian way she understands the idea of lost time better than these men, if for no other reason than she has experienced so much of it that it doesn’t impress her anymore. She looks at the aging Henrik as only someone could who once held him as a baby.

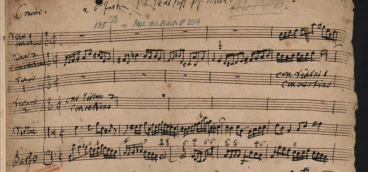

Just as subtle as the acting is the numinous set designed by Johnmichael Bohach and lit by Andrew Ostrowski, which becomes a character itself. Mark Whitehead’s sound designs — including bird, clock, and piano emanations – are so faintly appropriate you don’t know if you’re making them up in your head or listening to them exogenously.

“Embers” runs for two hours with a comfortable intermission, but it doesn’t feel like a long show, as the writing and delivery keep the action – that is, the conversation – moving forward at just the right speed.

There is a startling denouement, but like everything else in this drama, you’re not quite sure if you’ve imagined it or not. Did what we see happen, really happen? Or was it just the dream of one character, following a path so worn in the chambers of his memory after 41 years, that the apparition of his long-lost friend finally manifested itself in his lonely room? We might call this kind of ruminative performance a “theater of the mind,” as what we are shown and what we are told may not converge. A play favors what is shown, while a novel, by definition, is the medium of telling. This hybrid work may not be sure what it is. But in a strong production like this, does it really matter?

EMBERS continues through May 25th at Carnegie Stage, 25 West Main Street, Carnegie, PA. $29-$61. www.kinetictheatre.org or (888) 718-4253.