Keeping your Deals

I never really wanted a dog.

But all eight of our children kept clamoring for a dog. One night—I think it was a summer night, because the Cardinals were in town—I finally said, “OK, you can have a dog.” Lots of cheering.

The oldest son said, “When?” And I said, “When I get back from St. Louis.” More cheering. And the oldest daughter said, “When are you going to St. Louis?” I said, “As far as I’m concerned, I’m never going to St. Louis.” Two years later, for business purposes, I finally had to go to St. Louis. And when I eventually returned home and drove into the garage, I had to break through a homemade sign that said, “Welcome home Dad, bow wow wow.” To this day, we still have a German Shepherd—not the same one, of course.

The point is, it’s key to keep your deals.

The first lesson of keeping deals has to do with what I call “friendship love,’’ the kind my dad and his two Central Catholic High School friends had when they got together after World War II and started Federated Investors. Friendship love, in C.S. Lewis terms, is perhaps the strongest of loves. It is not exclusive and allows for others. It is what enables a company, a community, to grow. It even plays a role in investment management. We sell investment products that don’t always do exactly what everyone expects them to do, so we work to overcome the various speed bumps in the investment management process to continue to have a relationship with our clients. Love is work.

We have a lot of people who enjoy working at Federated; dignity is the key. If there is dignity in a human being, there must be dignity in the work that the human being does. And if there’s dignity in the work—and the product of that work is money that we manage—you could say we manage dignity. And our goal is to keep aiming for excellence in each part of our work. It was Aristotle who told us that we are what we repeatedly do, so excellence is not an act but a habit. We try to get people in the habit of trying to do things well. How do we know if we are doing a good job? Everyone who comes into one of our mutual funds has the right to get their money out for any reason or no reason, and I can assure you that if people were excited and wanted to change things, they would. Right now, we manage about $370 billion. I would think this is some indication that we are doing at least a decent job.

What about the role of Pittsburgh? When my dad and his buddies wanted to start the company, they wanted to start in Pittsburgh because there weren’t any investment management firms here. And there was the Pittsburgh work ethic and the Pittsburgh people. They aren’t just important to Federated, they are absolutely essential. I live on the same street in the city of Pittsburgh that I lived on when I was in grade school, when I was in high school, and all the way back into the ’50s. And today we live, in fact, in Mister Rogers’s house where he raised his children. So I thought I’d quote a little bit from Mister Rogers on the nature of community: “All of us at some time or another need help, whether it is giving or receiving help. Each one of us has something valuable to bring to the world. That’s one of the things that connects us as neighbors, in our own way—because each one of us is a giver and a receiver.” I think he defined community pretty well.

There have been tumultuous times. The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, was crisp, cool and absolutely pinprick clear in New York City. We were the last plane to land in Teterboro that morning at about 8:30. As we crossed the George Washington Bridge, we could see smoke billowing from downtown. We turned on the radio and found out what happened. As we got to the end of the bridge the traffic was stopped, and the police were allowing all the volunteers to run downtown from places north. These were all young men who were keeping their deal and who gave their lives in order to do it. Back in Pittsburgh, a plane went down over Somerset, and we were evacuating our building. My dad was there and, because he had been at West Point, decided he wasn’t going to leave. My brother went in to see him and said, “Look there’s two things working here. One, if you don’t go, there are going to be a lot of people in this building who won’t go, either. But even more important, we have this big sign on top that says Federated, and maybe these guys aren’t so hot at English—maybe they think it says ‘Federal,’ and we might be a target.” He eventually left. Then we ran into the problem of what to do with closed markets. When you think about it, the solution was community—the community of interest, the resiliency of the American spirit. It was people keeping their deals and working together.

What happened in 2008? This is the story of a lot of people not keeping their deals. I’m going to list groups of people that I think did not keep their deal in the 2008 crisis. The first are the people at the Fed. Among other things, they decided to print lots of money, and there’s never been a bubble without a lot of money being printed. Next are the people in Congress. OK, you can blame Congress—it’s nice to blame an institution—but it was the people in Congress who said things like, in respect to American money and with the mortgage system, “let’s continue to roll the dice.” It was a good idea to own homes; not such a good idea to continue rolling the dice. Thirdly, there are the people at banks who sold loans to people with no income, no job or assets. These were not proper loans. Then fourth, there are the people who bought stuff they couldn’t afford. Yes, they were conned into it, but in the end they bought stuff they couldn’t pay for. Fifth are the people at rating agencies. They took a stake in a lot of the projects that they put together. This is the same as if you go to a basketball game and the referee gets a percentage at the gate. It’s just not going to work very well, and it changes the dynamic of how the ref thinks.

And finally, the easiest of all—Wall Street. There were lots of people there who packaged up things, sort of knowing they were weak. And they used Boss Tweed’s theory of investing: “I seen my opportunities, and I takes ’em.” Compare this to Churchill’s ideas of responsibility: “The price of greatness is responsibility.” The politicians’ and regulators’ response is, “I will take all of the responsibility as long as someone else takes the blame.” This isn’t my idea of keeping your deals. So what is the response to broken deals? Well, the response to broken deals is generally about more regulation, and we’re getting plenty of that.

Which brings me to an issue which we think is a good deal—money market funds. Money market funds are simply a product in which you put a dollar in, get the dollar back and get some interest in between. It’s not complicated, and it’s a great business—$2.7 trillion is in these funds right now at zero or no interest. Since these funds started in 1971, we’ve moved $321 trillion through money funds successfully. They have paid $210 billion more to actual human beings who are in them than they would have gotten in their bank accounts. There are 56 million investors in these funds. These funds provide two-thirds of the short-term financing for municipalities, about half of the short-term financing of corporations, and about 25 percent of U.S. government securities on the short end.

And this great industry that we love and participate in was strengthened in 2010, well before Dodd-Frank was even written, much less passed. That’s because money funds asked the chairman of the Fed what should they do and he said they should improve the quality, reduce the maturity, and enhance the liquidity of money funds. All three of these things were done, in addition to other important things. And then all this was subsequently road-tested by the Greek debt crisis, by European bank problems, and by the U.S. losing its long-term AAA credit rating. None of this hurt money market funds because they had been strengthened.

So what was the government’s response? To call money funds “shadow banks” in need of more regulation. Well, money funds are not like banks. They have no leverage, they don’t make loans, and they are 100 percent capitalized. And they’ve never been bailed out. And if you look at the history of regulation, it’s interesting to note that, according to the FDIC, since 1971 you have had more than 2,900 banks fail at the cost of $187 billion to the U.S. taxpayer. And you have had no money funds fail (two paid slightly less than $1.00), and none of them got a cent of U.S. money. I am reminded of one time when my oldest son came up to me and said “Dad, what is Hell?” I’m telling him about good boys and bad boys, and that you have to obey your father in order to get to Heaven. I am so happy to be answering. Then I look at him and his face is all contorted. I said, “Do you understand anything I just said?” He said, “No, what does it mean when you say, ‘What in the hell is going on around here?’”

So you have to find out what the question is. To us, the question is the resiliency of money funds. That enables us to keep our deal. One of the principle reasons for us to keep our deal is that the deal is set by the Investment Company Act of 1940, which was passed to correct the abuses of the ’20s and ’30s. It’s safer to honor and do what’s in the best interest of the shareholders of the funds—not do what’s in the best interest of the whimsy or heartfelt decisions of regulators.

We believe in defending good deals. We believe in the strength of community, the human spirit, and the neighborhood. The foundation to all of this is the dignity of the human being, their work and thereby the marketplace, and, always, love. Be you teacher-student, business person-client, parent-child, keeping your deals is important so that, in the end, we get to hear, “Welcome home from Pittsburgh, my child, bow wow wow.”

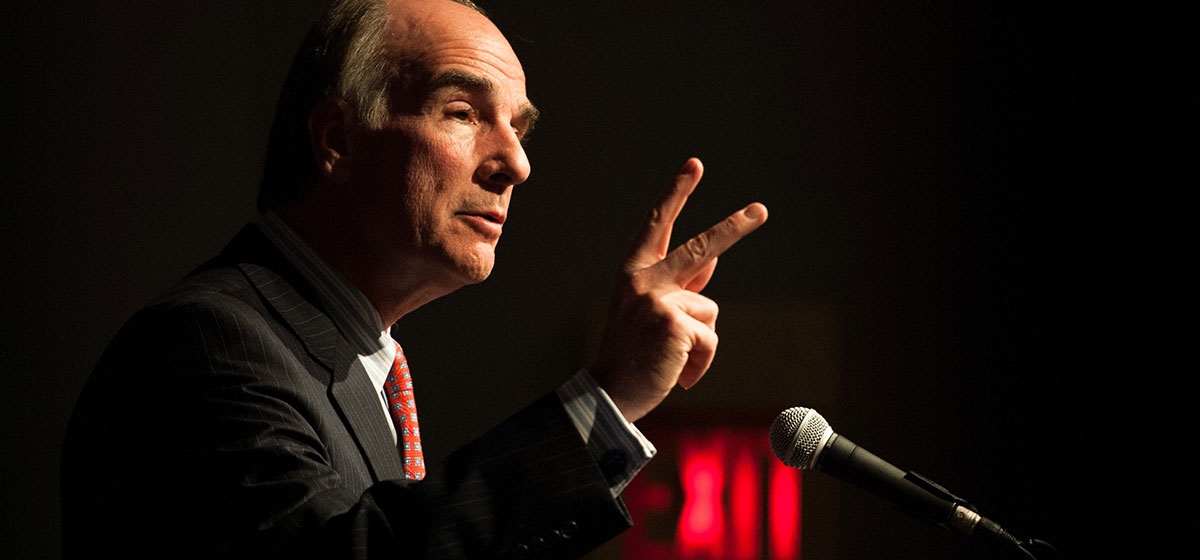

Christopher Donahue is CEO of Federated Investors. For a recording of the full speech, please visit pittsburghquarterly.com.

Editor’s note: Federated Investors CEO Christopher Donahue spoke recently at the quarterly CEO speakers series hosted by Pittsburgh Quarterly and Robert Morris University on its Moon campus. The above is his speech, somewhat abridged.