Keep Warm and Watch for Flickers

Forty below zero isn’t cold if you dress for it. I learned that in the Wyoming backcountry when I spent three weeks winter camping one February. We ate high-calorie diets, slicing butter into hot cocoa for the extra fat, and built thick snow shelters to pass the frigid nights. When it dropped below zero, we were toasty in our igloos, where the temperature hovered just around freezing. It won’t get that cold this winter in western Pennsylvania, or at least we hope. But if the polar vortex swirls again or we get pipe-busting weather, one thing is certain: The birds will be prepared.

Last December, when volunteers ventured out to survey birds for the annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count, it was 15 degrees outside. Birders counted 77 unique species, numbering some 25,000 individuals. Cold? Birds can deal with it. Layers of feathers trap air around their bodies. Core temperatures that average 104 degrees warm that air and allow birds to survive winter. Our winter residents stoke their feathery furnaces with seeds, frozen berries and the occasional insect or spider gleaned from bark crevices. Of course, they appreciate human handouts: Birdseed and suet feeders are a source of extra avian sustenance and seasonal joy for us, the watchers at the windows.

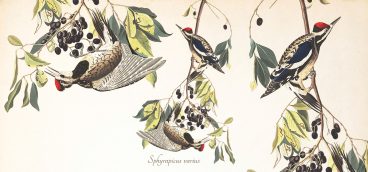

Of those wintering species, a less common but stunning bird is the northern flicker. A large woodpecker that sings a startingly song in spring and summer, flickers are about a foot tall, with black whiskered faces, black breast bibs, spotted chests and back, and a red-striped nape of the neck. Their wing feathers are shafted with yellow. When they spread their wings, it’s like watching gold dust being sprinkled.

Flickers are migratory, but some individuals stick it out and remain in our region. Last winter only 33 flickers were counted in December, but they are out there. They might venture to a suet feeder, so sharp eyes are helpful. Stiff black tail feathers prop them up; black feathers are strongest in all birds. Flickers will use their bills to excavate and probe, searching for tasty morsels. Just as I learned in Wyoming, you have to feed that furnace to keep up the heat.

Come spring, flickers are unusual in that they feed on the ground, grabbing ants, a favorite food. Look for them around the base of trees and along roadsides where softer, disturbed earth makes ants work easier. Flickers float down to those repasts with glee. When they take off again, look for a white patch on the rump, a great field mark that can confirm your identification.

Flickers are drummers. They mark territory with loud raps that fill spring with their soundings. I’ve often spotted them on dead standing trees, ubiquitous on Pittsburgh hillsides. Like all woodpeckers, they are cavity nesters, laying five to eight plain white eggs and incubating them for 10 days to two weeks.

Before flickers return in force next spring, consider joining the Audubon Society for its Christmas bird count (www.aswp.org). If you dress for it, you may spot one of these wondrous birds, and you’ll find the warm company of our region’s birders to while away the winter.