Into the Woods

June 15th was crisp and cloudless. carrying a chainsaw, orange surveyor’s tape and a compass, I started walking in a straight line into the pathless woods.

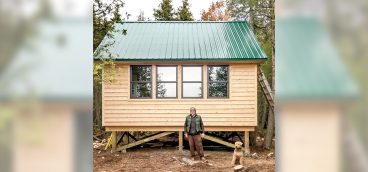

Trailing me was my Airedale, Hawkins, and behind both of us was the little cabin that a group of friends and I built the previous summer on an island in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. I set out to mark the route for a power line connecting the cabin with the nearest utility pole, half a mile away. I’d investigated the off-grid options — solar, wind and hydro, along with propane, diesel and gas generators — but they were insufficient in different ways. So when the power company gave me a price that was good for 90 days, I headed into the woods, aware that I was embarking on the biggest physical project of my life.

I’d owned the 135-acre property since 1988, but this section of dense, interior forest was a place I’d never been. It was cool, dark and quiet. Sunlight occasionally streamed through the tall trees in streaks that changed and shimmered as the wind blew the swaying treetops. At first, I walked quietly, like an Indian as we used to say as kids, trying not to snap a twig, listening to the forest. These were woods where no one had lived since the French explorers in the 1600s and probably much earlier. Given the remoteness, I wondered if another person had ever stepped where I was walking.

In places, I crashed my way through, breaking branches and cutting fallen logs. It was sometimes so thick that Hawkins couldn’t follow me over and between multiple logs or a phalanx of jutting sticks. Last summer, Hawkins spent four months in the woods as a year-old puppy. This summer, he was that much bolder, following scents so far away that I could barely hear him barking. I called, often to no avail. When he barked frantically nearby, I tracked him down, interrupting his occasional attacks on porcupines that left me busy removing quills from his snout. Mainly, I worried about coyotes, which were near. But he always came back, unscathed and happy as could be.

My satisfaction after marking the route was brief, as I eyeballed the magnificent trees directly in the way. For overhead power, I would ultimately have to clear a path 30 feet wide from ground to sky. That huge swath — 2,600 feet long — would include towering white pines 125 feet tall, clumps of beautiful white birches and spruces that rose 80 feet like arrows. I didn’t want to kill those trees. Nor did I want to tangle with them. I was experienced enough with a chainsaw to know that huge trees escalated the inherent danger.

So if the first plan had been to make the route as straight as possible, the second became: find the path of least resistance. I continued, day after day, searching for new routes where the trees were thinner, dead or blighted.

As I crisscrossed the woods, I became more familiar with them, but they were still so thick and wild that occasionally, I became disoriented, recognizing nothing and feeling a brief surge of that ancient fear of being lost and alone. But even the worst moments -— persistent mosquitoes, a branch whipping me in the eye or tumbling over an unseen obstacle — paled compared with the wonders the woods bestowed.

The biggest cedar tree I’ve ever seen — 10 feet around and I guessed 300 years old — had yielded to gravity and was now living the rest of its life horizontally, a massive roadblock with most of its surprisingly shallow roots jutting a dozen feet in the air.

In another area, a sudden high-ground ridge gave rise to a still higher, narrower ridge that was crowned by a gnarled old pine. Occasionally, treeless patches of sunlit, pale green ferns and wild blueberries appeared like oases in the dark woods.

And once, as I cut my way through the edge of an impassable thicket, a large, dark animal suddenly emerged and disappeared, leaving a mystery. It wasn’t a raccoon, or a beaver, or a porcupine. Not a groundhog. It wasn’t anything I’d ever seen, and when I looked it up, one possibility was a fisher, but at about 30 pounds this was too big; the other was a wolverine, but they’ve supposedly been gone from Michigan for 200 years.

The most fascinating discovery was a thick two-acre grove of dead, 12-feet balsam firs that crowded together like bristles on a hairbrush. The thin, gray, needleless spines were draped with curly gray-green lichen the locals call “old man’s beard.” To get through, I had to cut a narrow path, and it was only upon setting foot in this area that I realized its salient quality.

With every step, my boots sank a foot deep into a vast, rolling carpet of soft, emerald green moss. The enormous field of thick, wavy moss was like a coral reef that had grown and grown, undisturbed. Occasionally, big healthy cedars broke the monotony of the dead balsams, tilting at odd angles from mounds of moss that rose three feet above the rest of the brilliant green lowland. Likewise, moss covered the stumps of once-great cedars, and beneath those stumps were caverns three feet deep and 10 feet wide — partially hidden black chasms that stretched unexplored under their thick moss ceilings.

It was like something out of a fantasy book — Narnia or “Lord of the Rings” — but this was real. I named it the Magic Moss. And being alone in the middle of it, you could imagine, perhaps even feel, the enchantment — benevolent fairies or evil spirits, depending on your turn of mind. As the key connector to my best path yet, I envisioned what it would look like after a giant machine with metal caterpillar treads ground through it, sinking a utility pole in its midst.

***

The Fourth of July would be my last day in Michigan for four weeks. I’d expected to finalize marking the route long before, but I thought I could finish it that day, despite the now 87-degree heat. Cutting a narrow path through thick woods is tiring in cool weather. In the heat, it’s utterly exhausting. I unstrapped the protective orange chaps I wore over my jeans, and after two hours, I noticed how tired my arms were — a warning that it was time to stop. But I figured I could complete the last stretch in an hour.

Minutes later, as I cut a small tree at my feet, the chainsaw slipped and a red stripe appeared on my jeans below my left knee. I quickly rolled up my pants to gauge the damage. Alone in the middle of the woods, I’d feared this situation. The gash was bleeding but not badly yet. I kept my jeans rolled up to apply pressure and headed for the boat, not running but not losing time. Hawkins followed right behind me.

Later, as the emergency room doctor stitched me up, I quipped that at my age I thought I was finished with battle scars. But I knew I’d been lucky. I was also concerned. I still hadn’t finished marking the route, and that was the easy part compared with the enormous and daunting task ahead of clearing the broad right-of-way.

But I finally realized that this project had its own timetable. When I started, I simply didn’t know what I didn’t know. And the more I learned about these woods and perhaps from them, the better the final path would be. Or so I hoped. All I could do when I returned was to keep trying and have faith that I’d finally find the way.

***

During the month away, I dreamed about the woods for nights on end. I decided that none of the many paths I’d marked was the one. I wasn’t going to ruin the Magic Moss and I also decided I wasn’t going to cut down any of the great white pines. There was still one route I hadn’t considered — the first path my old friend Chris and I had cut through the property 20 years ago.

When I returned in August, I examined what was left of that path. We had cut it for a reason all those years ago. It had been direct and, thanks to a micro burst, relatively clear in some areas. Years of growth had changed that but not completely. From the utility pole for about 1,200 feet, this path would work for overhead power.

The trouble was that the rest of the route led through the best white pines on the property — including some that are 200 years old. I decided then I’d do the next 1,400 feet underground. It would be considerably more expensive — hiring an excavator for the trenching and buying conduit at pandemic prices. But I could earn more money. I could never replace those trees.

For the next month, I perfected the route, making countless alterations to save a handful of ancient cedars. I’d become obsessed with saving as many as I could — my duty considering the tree massacre to come. Finally, in late September, I started clearing the broad path.

My cousin and a friend helped the first two days, and we made good headway, giving me a big psychological boost. I would have been happy to have more help, but I wasn’t afraid to tackle it by myself either. I didn’t want to pay someone to do the job. I wanted to walk the land, understand it and decide where this permanent line would go. Plus, it would be great exercise, if it didn’t kill me. And finally, being just shy of my 60th birthday, I was aware that this might be the last time I could undertake such a challenge on my own. For that reason alone, I was all in.

Each day, rain or shine, Hawkins and I got in the boat, drove to the southern end of the island, and I carried two chainsaws a quarter of a mile in and out again at day’s end, one foot in front of the other back to the boat. At the beginning I could do three and a half hours a day. By the end, seven.

Clearing the 1,200 feet long right-of-way for the overhead power line —30 feet wide from ground to sky — was a monster. But instead of despairing about the amount of work ahead, I focused on how lucky I was to be healthy enough to do it and in such a beautiful place.

And it was beautiful indeed. Over the weeks, the leaves turned, and the ferns changed from deep green to deep red and ultimately a dry and dusty brown. After a wet week, the forest floor blossomed with the biggest array of different mushrooms I’d ever seen. Within a week, they were gone, either eaten or withered away.

I cut trees and fallen logs, dragged them to the side of the path and threw them into big piles. Branch after branch. Log after log. Pile after pile. For 25 days. The cooler weather helped, and I took two-minute breaks when I could hear my heart pounding. Sometimes I thought the muted, concentric thumping of a partridge drumming its wings was my own heart, beating abnormally. And sometimes I could hear both simultaneously, competing with their different beats.

Though I’d spared many in choosing the route, 17 good-sized cedars had to come down. I’d saved them for last, and by that time, I’d become good enough with the chainsaws, a couple of wedges and a sledgehammer that the trees fell just where I wanted. I hated the idea of wasting all that wood, so I visited a friend on a neighboring island who showed me his portable sawmill, how big the logs had to be, and how to trim them. In the last week I set about that task. After trimming the branches, I got on my knees and rolled the logs to the edge of the right-of-way. By the end, I had 55 logs that I’ll mill into boards next summer and use to make future outbuildings. That’s the theory, anyway.

The weather was getting colder, and keeping the old cottage warm was a challenge. The end of four months work was near, though, and my excitement grew. I told Hawkins, “We just have to make it through the last two days without your getting in trouble or my getting injured.” Which we did.

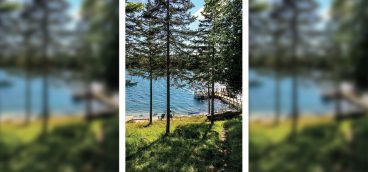

It was early afternoon on the final day, as we pulled away from my crooked little dock. I had loved being in the woods and away from “civil society,” but now I was ready to return — mission accomplished. As we slowly traversed the narrow channel, a huge bald eagle appeared from over my right shoulder, hovering just ahead of us for what seemed a deliberate amount of time before finally disappearing into the woods. Farewell to the island for another year.