Intersections: Poetry, Photography and Pittsburgh

In a 2006 lecture at Scripps College, art critic and L.A. Times reviewer Leah Ollman spoke on the overlapping aesthetic qualities used in photography and poetry, stating that “Each has a multiplicitous nature, and like any medium, resists a singular definition. Photography is said to be a slice of reality, a distortion of reality; a moment petrified, a moment prolonged; a way of freezing time, a way of slowing time; a means of devouring time and honoring time, defying it and yet succumbing to it. Is a photograph a moment embalmed, or a moment revivified? Does the photographic act clarify or does it complicate? Poetry emits the same deliciously mixed signals; it refutes the same kind of succinct summation that it itself can be so good at.” It’s with this kind of thinking in mind that PQ Poem looks to highlight local poet Joan E. Bauer’s upcoming 2021 collection The Camera Artist, which uses the photographic images from a host of the genre’s legends, including Squirrel Hill’s Saul Leiter, as a way of reimagining the poem as a visual mechanism.

While Bauer’s poems stand on their own, her ekphrastic piece featured below, “Saul Leiter: A Passion for Color,” fired a curiosity concerning this Pittsburgh native-son who moved to New York and became an artistic trailblazer in the just-emerging world of color photography. It’s a pleasure to be able to highlight Bauer’s work and an honor to pair them with some of Leiter’s photos and paintings, generously donated for use by Michael Parillo, associate director of the Saul Leiter Foundation. The photos and paintings add an eye-catching vibrancy, making it easy to see how they could inspire. It also feels significant and overdue to be giving an artistic innovator who got his start locally a bit of the attention he’s long deserved.

— Fred Shaw, editor, PQ Poem

Saul Leiter, Red Umbrella, circa 1955.

© Saul Leiter Foundation, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

On the Making of The Camera Artist

by JOAN E. BAUER

My work on the manuscript that became The Camera Artist began ten years ago. Over the years, the manuscript had various titles, but at first, only a handful of poems that touched on photography. The manuscript was accepted for publication, but after uncertainty and delays, I withdrew it in frustration and with the hope I could reshape it into something better with more time, effort and reflection. As I reworked the manuscript, I added a long poem, “The Camera Artist,” about Robert Frank; ultimately I broke that poem into three parts so that his story could unfold throughout the book. I read about Vivian Maier’s street photography and knew right away that I wanted to include her story. As I added more poems, the book’s center of gravity shifted. A friend read the manuscript and suggested “The Camera Artist” should be the book’s title.

I grew up in the fifties and sixties avidly looking at photographs in LIFE magazine where the work of Margaret Bourke-White, W. Eugene Smith and Dorothea Lange had appeared, so it was natural that I’d want to include them in this collection.

My partner Don Staricka is a serious lifelong photographer. We go to photography exhibits and galleries wherever we happen to be. In New York I first saw the photographs of Vivian Maier and in LA, a big collection of work by Cindy Sherman.

Years ago I’d seen the monumental collection of Pittsburgh photographs by W. Eugene Smith at the Carnegie Museum of Art, but I only felt I could write about him after seeing his photo essay about mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan.

Along the way, I couldn’t help thinking how much poetry and photography have in common: storytelling, the evocative image, choices made about focus and scope, light and shadow, tone, framing devices, texture and repetition.

Over time, I realized that there were cameras half-hidden in my poems, even in poems about childhood, John Berryman, Frida Kahlo and the space program. By then I knew I couldn’t let the book go without considering the work of Diane Arbus, Roy DeCarava, Berenice Abbott, and Toyo Miyatake.

One of the last poems I added was about Saul Leiter. My partner Don purchased a small grey volume of Leiter’s photographs at the Getty Museum. It was in our living room for a while before I picked it up and began thinking about these unconventional and transcendent photographs.

Leiter grew up in Pittsburgh, the son of a Talmudic scholar. I greatly appreciate both his immense talent and his humility. And I like what he said about his muse Soames Bantry: “We stumbled through life together.”

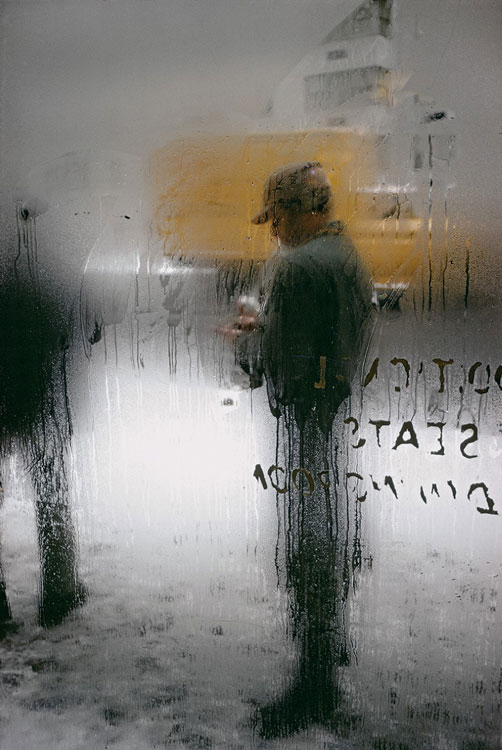

Saul Leiter, Snow, circa 1970.

© Saul Leiter Foundation, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

Saul Leiter: A Passion for Color

‘Red Umbrella’ (1955) Through a rain-splattered car window,

a dark & huddled figure

approaching a sharp-finned, yellow sedan.

‘Snow’ (1970) Yellow truck & man with a workman’s hat

observed—through an icy glaze.

Words stenciled on the glass, unreadable.

The workman’s legs, a dream-like blur.

*

The father, a renowned Talmudic scholar,

wants his son to be a rabbi.

The son studies for a year, then flees

to New York City—to escape his father,

become a painter.

The mother thinks he can still be a rabbi,

but paint on the third floor.

Who would know?

*

His mother gives him a Detrola when he’s 13.

He trades prints by W. Eugene Smith for a Leica.

Smith tells him he can probably ‘make a living’

with photography.

By the fifties, he’s pioneering color,

using Kodachrome.

*

In his East Village apartment,

a maze of knickknacks, books, palettes, brushes, boxes.

High ceilings. A bay of wall-length windows.

His paintings & those of Soames Bantry

on the cracked & peeling walls.

In interviews, Leiter’s voice is slow & halting

with a self-deprecating laugh.

My ambition was to pay the light bill.

*

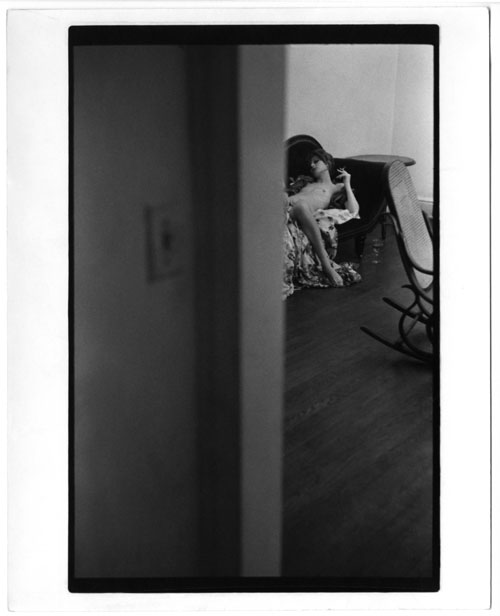

In his photographs of Soames Bantry,

she’s nude, languorously reaching from the bed

for a cigarette on a cluttered table

or standing & laughing,

half-swathed by a shirt.

We stumbled through life together.

*

Leiter seems bemused by how his life unfolded,

his work ‘discovered’ at age 82. He says:

I could have built a career, but instead went home

& drank coffee, looked out the window….

I don’t have a philosophy. I have a camera.

Saul Leiter, Soames, circa 1965. © Saul Leiter Foundation, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.

“The Beauty of Simple Things”

by MICHAEL PARILLO

Of the prominent Pittsburgh rabbi Wolf Leiter’s three sons, the one deemed most worthy of succeeding his father — the most intelligent and charismatic, with the highest natural aptitude for reciting passages from the Talmud — was the second son, Saul, born on December 3, 1923. Saul Leiter, however, had his own plans, and in 1946 he shook off the burdensome expectations of his family and moved to New York City, where his nascent love of painting and taking photographs would quickly blossom, and where he would reside for the rest of his long life.

It was in Pittsburgh, though, where Leiter caught the bug. He started painting as a teenager, and he owned an inexpensive, easy-to-use Detrola camera that his mother gave him in the late 1930s. His first photographic muse was his younger sister, Deborah, who gamely played along in pictures taken on the porch of the Leiters’ Squirrel Hill home and in locations such as Schenley Park.

In 1945, a couple of years after dropping out of rabbinical college in Cleveland, Leiter gained some early encouragement when his paintings were exhibited at Pittsburgh’s Arts and Crafts Center, earning a review in the Post-Gazette. “The next great upheaval in modern art may well begin in Pittsburgh instead of Paris,” Lloyd Mallen wrote. “Like Andre Derain, Modigliani, Toulouse-Lautrec, and other major figures of French modernism, Leiter is self-trained. Like them, he uses form and color boldly, depending only on his native poetic instinct to create his effects.”

Many of the same words could be used to describe Leiter’s uniquely poetic photographs. Leiter, who did the majority of his work in and around his home in downtown New York, found beauty and mystery in the most ordinary settings, making the most of everyday motifs including umbrellas, snow, and condensation-streaked glass. “I happen to believe in the beauty of simple things,” the artist said in a 2006 WUWM “Lake Effect” radio interview. “I believe that the most uninteresting thing can be very interesting.”

In the late 1950s, looking for a way to earn a living with his camera, Leiter entered the world of fashion photography, and soon began appearing regularly in magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar and Nova. He traveled widely on commercial shoots and enjoyed a successful career through the 1960s. When art directors started meddling in his work, however, he turned his back on his fashion career. Leiter wouldn’t find himself in the spotlight again until 2006, when his first book, Early Color, was published, revealing his miraculous street photography to a world that was finally ready for it. (Its content, largely from the 1950s, had been captured in a time when color wasn’t readily accepted as serious fine art.) That book was followed by Early Black and White (2014) and the nudes collection In My Room (2018), among many others, along with solo exhibitions around the world.

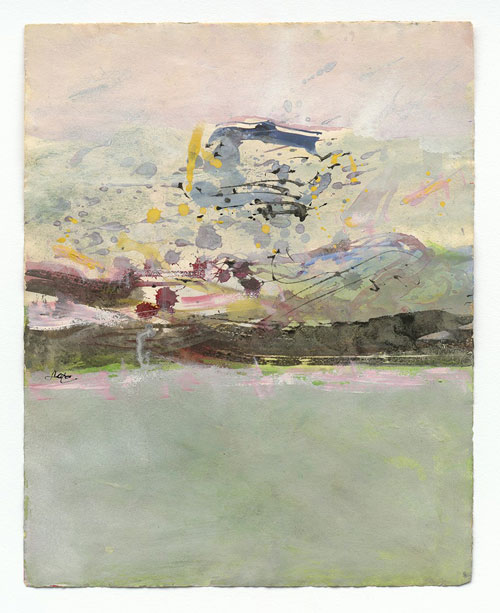

Although he’s known primarily as a photographer, Leiter was also an active painter until his death in 2013, just a few days before his ninetieth birthday. His paintings share with his photographs a dramatic sense of composition, often containing large blocks of a single color, with most of the “action” confined to smaller areas.

In a 2013 interview with Vince Aletti at New York’s School of Visual Arts, Leiter said, “I think the reason I developed something on my own: I didn’t know better. I did what I wanted to do.”

Saul Leiter, Untitled, undated. © Saul Leiter Foundation, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery.