How Baseball Brings Us Together

A. G. Spalding once claimed that baseball likely began with the simple act of a boy tossing a ball into the air. The poet Donald Hall, who wrote a book about Pirates maverick pitcher Dock Ellis saw this simple act evolving into “sons playing catch with fathers” and eventually into a game “on a diamond that encloses what we are.”

Baseball has a way of bringing out our best by linking us together. Cultural historian Jaques Barzun actually went as far as to claim “that whoever wants to learn the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.”

Over the years, novelists, historians, biographers, and journalists have praised what they have called America’s game for the way it creates a bond between generations of families. In Wait Till Next Year, presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin remembered her father taking “his daughter” to her first game at Ebbets Field, and the time, after his passing, that she took her sons to Fenway Park. When she saw her sons in the place where her father once sat, she felt “an invisible bond between our three generations, an anchor of loyalty” linking her sons to their grandfather “through the game of baseball.”

In The Glory of Their Times, baseball’s first oral history, Lawrence Ritter wrote that his father inspired the book. At first, Ritter thought that his interviews of old-time ballplayers was inspired by the death of Ty Cobb, but later he realized that his father had died about the same time: “Still vivid is my memory of the day, when I was nine years old, when my father took me by the hand to my first big-league baseball game. It seems to me now that I was trying to draw closer to a father I would never see again.”

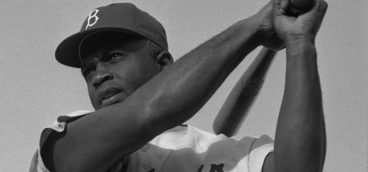

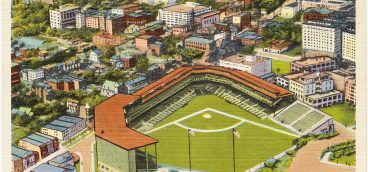

Like Doris Kearns Goodwin and Lawrence Ritter, I have a vivid memory of going with my father to my first baseball game. I remember that my Pirates played the Reds in a game that took place in the spring of 1948, making me nine years old at the time. The Pirates won the game and Ralph Kiner, who would become my baseball hero, hit two home runs off Ewell Blackwell, a side-winding right-hander who had a reputation for throwing at batters and claimed Kiner was afraid of him.

Years later when I visited Cooperstown and told the Baseball Hall of Fame librarian about my memory, he sent me a box score of a game played on May 2, 1948 and won by the Pirates, 6-4. In that box score, I found that Ralph Kiner had hit two home runs off Ewell Blackwell. I also discovered that Frankie Gustine, who owned a restaurant just up the street from Forbes Field, played that day for the Pirates, as well as Danny Murtaugh, destined to manage the 1960 and 1971 World Championship Pirates.

There was yet another delightful surprise on that page of box scores. In a brief summary of the game played a day before, on May 1, between the Reds and the Pirates, I read that Pirates pitcher Fritz Ostermurller, had “hurled the rampaging Pirates into first place a half game ahead of the Giants.” That meant that the Pirates, doomed to be the doormat of the National League through most of my childhood, were in first place when I went with my father to my first big league game.

My relationship with my father was rocky during my teenage years, but our love of baseball was the one thing that brought us together. There were so many things that divided us, but we still could talk, or mostly complain, about the Pirates as we watched them bumble their way to another losing season and waited till next year.

In 1960 when I turned 21, next year finally came to Pittsburgh, When Bill Mazeroski hit his miraculous World Series winning home run, he brought long suffering generations of Pirate fans together in celebration, including my father and his son.

Of all of my baseball memories, good or bad, not one stands out like the day my father told me that Ralph Kiner hit those two home runs because he knew it was my first game, or the day that I saw a baseball soaring through the heavens at Forbes Field and the most unassuming of ballplayers circling the bases and waving his cap. The first brought a father and son closer together. The second brought an entire city together.