Hidden from History

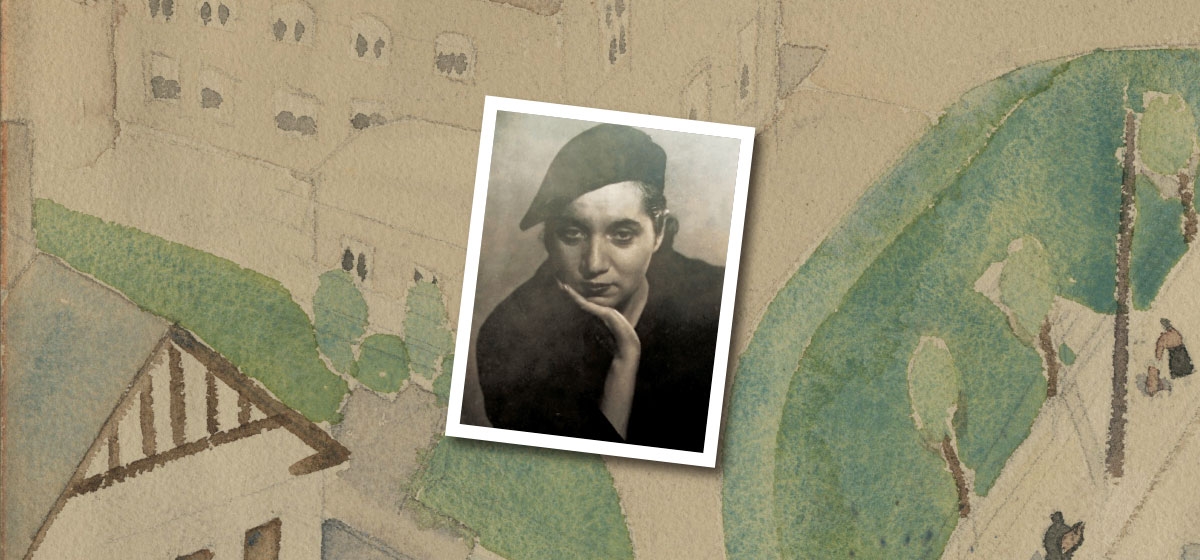

The life of Esther Phillips (1902– 83) would have languished in obscurity, at most a footnote in history, were it not for the dedication of a few friends and supporters. Her story, which intersects with ideas about women, class and mental health in the 20th century, is all too familiar. An obstinate, free-spirited woman, she defied family expectations to contribute to their greater good by pursuing her passion for art. She rarely held a job, turning frequently to a small group of artistically minded friends for support. She was flighty and irresponsible, living the bohemian lifestyle with other artists in Greenwich Village once she abandoned Pittsburgh in 1936.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”107″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

The harsh realities of her chosen life almost broke her. Like many women who dared to operate outside the norms, she was deemed unstable when it is likely that poverty and the lack of the basic necessities—a common anecdote has her eating ketchup on crackers for dinner—damaged both her body and her mind. In fact, her 6½ year sojourn in an upstate New York asylum proved beneficial because she had a stable routine, regular meals and some kind of healthcare. There, a sympathetic librarian encouraged her with books and art supplies and had her write anecdotes about her life in the Village. Phillips was adept at attracting people who tried to further her career and provide basic necessities, and she achieved a modicum of success, showing and selling in both Pittsburgh and New York City, though she never achieved the success she felt she deserved.

The artist obsessively and determinedly pursued her passion, over coming numerous obstacles. She sought an education by taking advantage of the neighborhood art school at the Irene Kaufmann Settlement in the Hill District, where Samuel Rosenberg inspired so many artists. His teaching methods focused on learning to look as well as learning to make, and Phillips must have soaked up his discussions about art and artists because there are obvious references in her work to Henri Matisse, the Cubists, and Americans Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, and above all, Stuart Davis. She might also have studied with Rosenberg when she was a part-time student at Carnegie Tech and even possibly with Robert Lepper, who taught Warhol at Tech. Either could have influenced her to look at her surroundings for subject matter, Rosenberg with his early gritty paintings of Pittsburgh and Lepper with his infamous neighborhood assignment. She spent time in the women’s reading room at Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh and at the Museum of Art, especially when she lived in an apartment across the street. She would have witnessed the introduction of European modernism at the Carnegie Internationals, but she probably saw much more of it later while living in New York City.

Her close friends in Pittsburgh included writers such as the eccentric Merle Hoyleman, and she was acquainted with artists Mary Shaw Marohnic and Milton Weiss, and architectural historian Jamie Van Trump. John O’Connor, who organized the exhibitions of American paintings at the Carnegie Museum of Art in place of the Internationals during World War II, was aware of her work and attempted to promote it, including it in exhibitions.

She was a member of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh and participated in their annuals; her work was included in shows around the city reviewed in the Pittsburgh papers. She submitted work for the Carnegie Internationals, perhaps because John Kane, a kindred spirit, participated, but Phillips’ paintings were never accepted. In New York City, she hung out with the art crowd in the Village, claiming friendship with Franz Kline and Edna St. Vincent Millay, and she found a supportive friend in Eugenia Hughes. She was hired as a teacher for the Works Progress Administration, another meager stipend, but she kept trying to get accepted as a WPA artist instead. She sold her watercolors at the Washington Square Outdoor Shows in the 1950s and made ceramics and jewelry for street stands, all the while observing how certain abstract artists were making it while other artists, like herself, were practically starving.

If it weren’t for her friends, and later, her family, her work probably would not have survived, and it still hasn’t been examined closely. Most of her work was done in watercolor, which requires a quick dexterity that seems to fit her quixotic personality. A studio mate once remarked that she didn’t have the patience for labor-intensive oil painting, and Pittsburgh critic Douglas Naylor found it difficult to follow her disjointed conversational shifts when he interviewed her. She set things down as quickly as possible, frequently using both sides of the paper, sometimes crossing out the less substantial work. Her subjects remained close to her life, the cityscapes of Pittsburgh and New York City that bore the marks of industry and technological innovation as well as a vitality and energy, even after the Depression.

Defying expectations, Phillips eschewed the harsh, almost journalistic realism so popular in both cities, and she assimilated avantgarde tendencies toward abstraction. Her cityscapes were constructed with the fractured planes introduced by Cubism, and her bucolic images of the grounds of the asylum had an organic quality that emphasized shape over exacting detail. And in her most popular works, the many depictions of the women and their activities in the asylum, her figures were suggested by a few curved lines, rather than shaded to give solidity, and were placed in patternlike arrangements across the surface without much interest in spatial complexity or depth.

The resulting play between representation and abstraction paralleled the increasing interest in flatness seen in the work of her more famous peers. The asylum works appeal because of her insider’s view of activities there with her fellow inmates bowling or reading, and because of our romantic notions about independent women who pursued careers outside the home or supposedly unstable women like the protagonist in the famous story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” published in 1892 by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. But what really interested her was the arrangement of shapes, whether her subject was women in the institution or boats in the harbor. While the institution images are usually muted, the landscapes and cityscapes exhibit the vibrant colors that were beginning to dominate much of the new abstract art. While not especially avant-garde, Phillips’s work was in tune with the times, even when she remained isolated and restricted in the asylum.

If it weren’t for her friends, and later, her family, [Esther Phillips’s] work probably would not have survived, and it still hasn’t been examined closely.

This sophistication is held in check by a simplification that perhaps comes from her lack of a consistent formal education. Her work has been compared with that of the so-called primitive artists, a term from that era, who have also been called outsider, selftaught, or visionary artists, those who followed idiosyncratic paths in their highly personalized styles. Phillips is frequently associated with John Kane, Pittsburgh’s favorite itinerant painter whose success with works shown at the Museum of Modern Art also brought harsh criticism from the art elite. Although many looked down at these free spirits, modern artists were more favorably impressed because they sought to incorporate childlike wonder and naïveté in their own works in an attempt to find more direct ways to communicate. Moving away from realism, they turned to African masks and the art of children or even the insane to rid their avant-garde work of centuries of realism and narratives, which they began to think of as kitsch made for the masses. Because of these concerns, the work of both Kane and Phillips had a better chance for appreciation in this era.

Both also interest us primarily because their art reflects their fascinating lives, feeding upon our stereotyped ideas about artists. Both lived on the fringes, the outskirts of polite society and the art world, obsessed with making art. While perhaps not the most important artists of their time, they add immeasurably to our understanding of the artistic personality faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles who nevertheless pursued artistic dreams. Kane has received critical attention, including a 1971 book by former Carnegie Museum director Leon Arkus that reprinted his autobiography, “Skyhooks,” which came out in 1938, but no one has yet tackled the stacks of Phillips’s drawings. Lisa Miles’ book “The Fantastic Struggle: The Life and Art of Esther Phillips” relies on correspondence, journals, hospital records and reminiscences to flesh out our knowledge of her life. Posthumous exhibitions at the former Carson Street Gallery and the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts will now be followed by one at Borelli-Edwards Gallery (Sept. 17–Oct. 22). But the job of cataloging and carefully examining her work remains to be done.

It is always tempting to contextualize an artist’s life and work with comparisons to others. Like Esther Phillips, who moved to Pittsburgh from Russia at age 5, Andy Warhol was born into a family that emigrated to the city from Eastern Europe. Both grew up poor and both ended up at Carnegie Tech, though Warhol managed to get a degree. He moved to New York City 13 years later than Esther Phillips did and made his way much more easily there. The one thing they shared was the knowledge that they were artists with a dedicated perseverance to their passion.