Henry Clay Frick: Blood Pact

Among the great fortunes of Pittsburgh’s Golden Age (1870–1910), that of Henry Clay Frick stands third, bested only by Andrew Carnegie and the Mellons. But the extraordinary aspect of the Frick fortune was not its size. Carnegie, Heinz, Mellon and Westinghouse were all entrepreneurs who exercised ultimate control in their operations.

Frick started as an entrepreneur, but his fortune was earned largely as a manager and chief executive officer. He is likely the best CEO this town has ever seen; beyond doubt he was the highest paid.

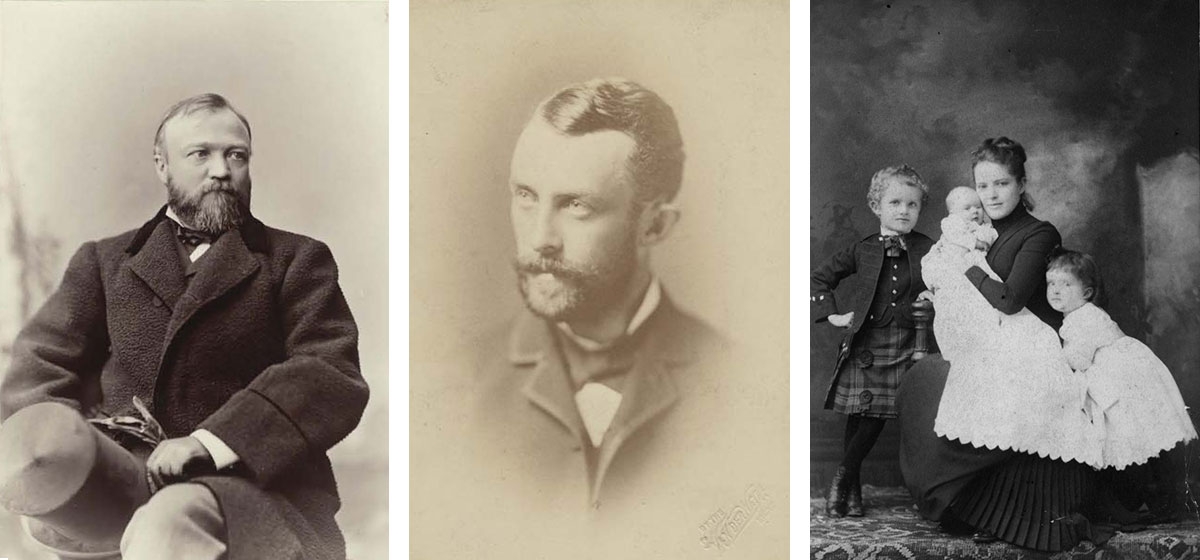

Henry Clay Frick was born Dec. 19, 1849, in West Overton, north of Connellsville, and named for Henry Clay, the former Speaker of the House of Representatives known as “The Great Compromiser.” His mother, Elizabeth Overholt Frick, was one of eight children of Abraham and Maria Overholt; they were Mennonites. Abraham, in addition to extensive property holdings, owned two distilleries. One was at Overton, where he also owned the one-street village, and the other was a large complex on the banks of the Youghiogheny at Broad Ford. Frick’s father, John, worked as a hand at the Overholt distillery and later scratched out a near-subsistence living as a farmer. The formative influences on young Clay, as he was called, came almost exclusively from the Overholt side. In Clay’s eyes, Grandpa Overholt was a rich and magnetic figure.

Never pleased with their daughter’s marriage to the hapless John Frick, the Overholts lived in relative opulence and did little to help the struggling Frick family. Clay both resented and emulated Abraham Overholt. He told his sister Maria, “Oh, I’ll be worth $200,000 some day.” That day would come sooner than he could possibly realize.

He began his career in 1863, at the age of 14, clerking in his uncle Christian Overholt’s store in West Overton. Two years later he moved to Mt. Pleasant, continuing his clerking career for his uncle Martin Overholt. He had sporadic college training at nearby Westmoreland College, and at Otterbein in Ohio; it was very thin varnish.

During this five-year apprenticeship, he began to manifest the traits that would make him a major industrialist. Abraham Overholt was an immaculate dresser, and, within his limited means, young Clay adopted his mode of dress. He impressed the patrons at his stores with his precise dress and manners, not with a salesman’s natural banter. At 19, he went to work for his cousin, Abraham Tintsman, at the Broad Ford distillery—still within the Overholt orbit. He quickly mastered the skills of bookkeeping. The books were kept with precision; his handwriting was almost artistic. He was fascinated by the cash circulatory system of inflows and outflows. Growing confidence turned to brashness one day when his grandfather Overholt visited: “Grandfather, won’t you tell me near as you can what my share in your estate would be?” he asked. “If I had it [now] I could make so much more out of it than you are.” He soon got his answer. Abraham died in 1870, leaving 10 percent, or $40,000 ($800,000 in today’s money), to Frick’s mother. Clay’s direct share: zero.

Beneath the rolling croplands around Connellsville lay the richest vein of metallurgical coal in the country—the eponymous Connellsville seam. Frick at 21 had the business acumen, the family connections, and most important, the vaulting ambition to ride its bounteous harvest to staggering success. He moved quickly.

Coke was gradually replacing charcoal and anthracite coal as the fuel of choice for smelting iron. Coke was produced in the 60-mile-long Connellsville coal fields by means of beehive ovens. They were 12 feet in diameter and seven feet high. Coal was fired in an airless chamber for 48 hours. Sulfur, phosphorus and other impurities were burned off, leaving nearly pure carbon. With burgeoning iron-making in nearby Pittsburgh, an inexhaustible supply of raw material and relatively low capital costs, coke-making offered an irresistible opportunity.

In 1871, Frick borrowed $75,000 against his mother’s share of her father’s estate. He went into business with his cousins, J.S.R. Overholt and Abraham Tintsman, and the venture soon became known as Frick & Company.

1871 to 1881 were years of frenetic activity. Hard upon the launch of the firm, Frick sought a $10,000 loan from an associate of Abraham Overholt¸ the formidable Judge Thomas Mellon. Frick was highly leveraged, and the loan was backed more by Frick’s character than by hard assets. The young man’s dress, demeanor and intensity persuaded the judge. With his oven project only half completed, Frick asked for another loan to increase capacity. The loan officer at the bank turned him down, but the judge intervened and sent his own mining partner, James B. Corey, to Connellsville for an inspection. Corey was duly impressed and reported back to the judge: “Give him the money. Land’s good, ovens well built; manager on job all day, keeps books evenings. Maybe a little bit too enthusiastic about pictures but not enough to hurt; knows his business down to the ground.”

Business was good, but in 1873 a financial panic sent the U.S. economy into a tailspin. Frick barely weathered the storm. His schedule gives a clue to his survival. Up at 3 a.m., he monitored his coke ovens and later went surveying distressed properties. By 10 a.m., he was in Pittsburgh soliciting coke orders, then back to Connellsville to do the books and catch some sleep.

Tintsman, on the way to bankruptcy, sold his shares back to Frick. Tintsman was also about to shut down the feeder railroad he owned, with potentially disastrous consequences for Frick. So Frick conjured a railroad solution to solve a railroad problem. He rounded up controlling options at distressed prices and then sold the railroad to the B&O, convincing them it would be a big moneymaker when normal coking activity resumed. The deal was done; Frick could get his coke to the market, and for his efforts he asked for, and received, a $50,000 commission. Hard pressed, his other partners sold their shares back to Frick. He paid with his commission money, and by 1875 owned Frick & Company outright. Opportunities to buy distressed properties kept coming his way, and Frick kept buying. He avoided excessive leverage by bringing in two new partners. He often pressed his luck, but never to the brink, and by 1878 he had 1,000 ovens producing 9,000 tons, or 100 carloads, of coke a day. Not yet 30, he was a millionaire and had earned the title of “the coke king.”

Frick deepened his ties to the Mellons through his friendship with A.W. Mellon. In 1880, when A.W. was 25 (six years younger than Frick), the judge gave him full ownership and control of T. Mellon & Sons. From that day forward, his word was law. The judge never questioned a single action; it was a brilliant call. A.W. Mellon’s financial genius would propel him to incalculable wealth and national fame, but Frick was the dominant personality in their lifelong friendship. To Frick, Mellon was always “Andy.” To A.W., his friend was invariably “Mr. Frick.” In 1880, Frick invited A.W. on a four-person trip to Europe. He purpose was twofold. The trip cemented his relationship with Pittsburgh’s most important, if not biggest, banker. Mellon’s money was always a little greener than the competition’s; it added cachet. Accompanying them was Connellsville coke operator A.A. Hutchinson, and before the trip ended, Hutchinson, enchanted by the charms of Europe, agreed to sell out to Frick.

A.W. performed another important service for Frick. He introduced Frick to his future wife. Or more accurately, he tried and failed. Attending a reception in June 1881 with Mellon, Frick inquired about a tall, slender woman with blue eyes and a soft smile. Mellon knew her; she was Adelaide Childs, the daughter of Asa P. Childs, the recently deceased shoe manufacturer and supplier to Frick’s Broad Ford company store. Frick asked Mellon for an introduction. Bowing to the etiquette of the day, Mellon set off in search of an older guest to properly officiate. It took a little time. Meanwhile, the aggressive Frick, panting and pacing like a bull in a pasture, headed straight to Miss Childs and performed the duty himself. Mellon was probably relieved.

Doubtless, 1881 was the most fateful year in Frick’s life. He and Adelaide were married on Dec. 15, and honeymooned in New York. There he met Andrew Carnegie for the first time. Carnegie and his forceful mother, Margaret, hosted a lunch for the newlyweds. At this lunch a second betrothal was solemnized. This time Frick sold Carnegie what would become a controlling interest in H.C. Frick. Flush with the glow of the moment, Carnegie proclaimed: “It will be a great thing for Mr. Frick.” Somewhat suspicious of the hard-driving Frick, Margaret Carnegie, in her thick Scottish brogue, asked: “Tha is a verra good thing for Mr. Freek, but Andra, what will be the gain to oos?” Afterward, Adelaide Frick received a beautiful bouquet from Carnegie. Frick urged her to write him a note. The note was never sent; Frick had sent the flowers.

Motivations on both sides bear some scrutiny. The Carnegie interests consumed large quantities of coke at both the Lucy furnaces and the Edgar Thomson works (ET), and they also produced coke themselves. At ET they had the lowest-cost rail mill in the world. The same could not be said of their coke operations. It was common knowledge that the “coke king” was a low-cost producer, as well as the most knowledgeable and dominant figure in the business. Through pushing on the part of his brother, Tom, and his longtime partner, Henry Phipps, Carnegie concluded that to fulfill his vision as the “king of steel” he must be an integrated producer—i.e., control his own sources of raw material. Frick’s motives in hitching his ascending star to Carnegie are less clear. From 1882 through 1888, Frick’s ownership of H.C. Frick Coke waned as Carnegie’s grew to 73.5 percent. And from 1883 on, Frick was an employee. Three lines of thought seem to have driven Frick into Carnegie’s orbit, leaving behind the independence his nature demanded.

First, with Frick it was not all about money. With Carnegie it was simple: make the money and then give it away. Both these efforts were inspired by genius. With Frick there were wider concerns—family, friends and art. The voluble Carnegie was at heart a loner. Second, Frick shared Carnegie’s vision of an integrated steel industry. There would ultimately be no coke king, only a steel king: Carnegie. Last, and perhaps most importantly, Frick was supremely confident in his ability to manage a vast enterprise. Despite being the “smartest man in the room,” Carnegie was never a hands-on manager. Frick knew he would be indispensable before Carnegie did. Frick’s relationship with the man who would ultimately control his destiny was contentious from the start. The Connellsville seam occupied only 150 square miles. Opportunities were limited, and prices were going up. Frick moved boldly to consolidate the dominant position of the H.C. Frick Company. In 1883, when Carnegie opposed a Frick coal acquisition, Frick was characteristically blunt. “I am free to say, I do not like the tone of your letter… In the matter of the properties in question… I shall have to differ from you and I think the future will bear me out.” Carnegie backed down.

The coal fields had a long history of labor violence, and early in his career Frick used strike breakers and private police to crush any union activity. To the end of his life, every fiber of Frick was anti-union. In 1887, H.C. Frick Coke Company and the Syndicate of Coke Operators were determined to suppress the striking mine workers as they had done in the past, but it was not to be. Early in 1886 Carnegie published his “Triumphant Democracy,” and in it he supported the right of working men to organize. To enhance his image as an enlightened capitalist, and perhaps to keep his furnaces going, he forced Frick to capitulate. Perhaps Carnegie perceived Frick as a threat and determined to take him down a peg or two. In any event, Frick responded quickly, resigning and going to Europe. Carnegie beseeched him to return, and before long he did. Frick had drawn a line in the sand, and Carnegie didn’t dare to cross it for some time. In addition to his strained relationship with Carnegie, Frick suffered two other tragedies. In 1891, his 6-year-old daughter Martha died as a result of a small pin she ingested at age 2. Adelaide and Frick blamed themselves, and the memory of Martha haunted them for the rest of their lives.

Frick did not blame himself (publicly at least) for the Johnstown flood, although rounding up the principal suspects, Frick was clearly first in line. In 1878, Frick, along with a tunnel contractor, Benjamin Ruff, purchased an abandoned reservoir 70 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. They solicited 14 other members for the exclusive South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Frick was the largest shareholder and a member of the executive committee. On May 31, 1889, a patently inadequate dam gave way, sending 20 million tons of water—in some places 70 feet high—smashing into Johnstown, and 2,000 people lost their lives. It remains among the top five “natural” disasters in American history. Frick isn’t alone in his culpability, though. Pittsburgh’s elite doubtless shared in the blame. One can only imagine, in this “golden age of the plaintiff’s bar,” what civil and criminal liabilities might have been imposed. For better or worse, it was a different age, aptly described in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, “The Great Gatsby,” a generation later: “They were careless people… they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness… and then let other people clean up the mess.”

Tom Carnegie died an early death in 1886. Despite a drinking problem, he did yeoman service as Andrew Carnegie’s right-hand man at Carnegie Brothers. Of equal importance, he was the lubricant separating any “metal to metal” contact between his brother and Frick. Henry Phipps became chairman, but was a reluctant CEO, gradually deferring important decisions to Frick. When Frick resigned in June of 1886, it had caught Carnegie and Phipps flatfooted. Despite Frick’s prickly personality, Carnegie knew he was indispensable to the running of H.C. Frick, and in leading the Connellsville Coke Syndicate. Furthermore, Carnegie sensed that Frick was becoming indispensable to the burgeoning Carnegie steel interests. Frick was the only man who could ride the tiger. After a five-month European hiatus, Frick was back on the job in November.

Phipps passed more and more steel responsibilities onto Frick’s willing shoulders and lobbied Carnegie to have the rising star take his place. In 1889, Frick became chairman of Carnegie Brothers. This time, he was playing a stronger hand, and he soon let Carnegie know it: “I cannot stand fault-finding and I must feel that I have the entire confidence of the power that put me where I am… I know I can manage both Carnegie Brothers and Frick Coke successfully.” Carnegie was conciliatory: “Now I only want to know how your hand can be strengthened.”

Frick not only squeezed efficiency and profits out of coke and steel; he acted strategically. When a start-up ET competitor struggled, Frick used predatory pricing to force a sale to Carnegie at a bargain-basement price of $1 million in long-term bonds. The deal was a home run, and Carnegie was elated. He was so confident in Frick’s capabilities that at long last he merged Carnegie Brothers (ET) and Carnegie Phipps (Homestead) into the newly named Carnegie Steel company in June of 1892.

Back in 1886, Frick had proposed that he transfer a significant portion of his H.C. Frick ownership to Carnegie for shares in Carnegie Brothers. Carnegie advised Frick against it and turned down the request. Later that year, after Frick returned from his European “sabbatical,” Carnegie changed his mind and granted Frick shares valued at $184,000. Further grants were made in 1888, 1890 and 1891, and finally, in 1892, when Frick became chairman of Carnegie Steel, his ownership rose to 11 percent—equal to that of Carnegie’s longtime partner, Henry Phipps.

Frick’s name will forever be linked to the infamous Homestead strike in the summer of 1892. Much of this opprobrium is well deserved; some is not. Labor violence in the coal fields was simply a way of life. Coal mining is a dirty, dangerous and, in those days, low-paying job. Unions were weak to nonexistent and would not be a viable counterweight to capital until the 1930s. Coal country labor practices had a familiar pattern. Business conditions worsened, wages were cut and miners struck, replacement workers were hired, violence ensued and private police or the state militia would quell the unrest. As the head of H.C. Frick and the de facto leader of the industry, Frick was anti-union to the core. The one exception was 1887, when Carnegie’s pro-labor posturing pulled the rug out from under Frick. When the miners struck again in 1891, it was the worst labor insurrection in the history of the H.C. Frick Company. This time Carnegie did not interfere, and Frick broke the strike. Of the 25,000 men on strike, 43 were wounded and 11 were killed. In several metrics, the strike was more violent than Homestead.

When the Carnegie interests purchased the Homestead works of an under-capitalized competitor, they inherited a union, The Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers. Frick had but one objective in dealing with the labor situation at Homestead in 1892. There was no negotiation; there was only a diktat. He intended to break the union.

Events proceeded in rapid succession. On July 1, he locked out the unionized workforce. On July 6, he barged 300 armed Pinkertons up the Monongahela River, ostensibly to guard the plant, but in reality to facilitate the safe passage of replacement workers—scabs. All hell broke loose. The Pinkertons were rebuffed, and both guards and strikers were killed. These traumatic events were called out in banner headlines across the U.S. and Europe. Frick played the heavy. Carnegie had gone to Europe in June (exactly where Frick wanted him) and did not return until early 1893. Privately, Carnegie supported Frick to the hilt, despite his posturing about deep feelings for the working man. The implication was that had he, Carnegie, been on the spot, things would have been amicably settled. Any fair weighing of the facts surrounding Homestead leads to the conclusion that Frick acted far more honorably than Carnegie. The latter did not raise a high bar. On July 12, 8,000 National Guard troops secured the plant. Replacement workers drifted in, and by November the strike was over. Charles Schwab was moved over from ET, and by 1900 Homestead was the largest of the Carnegie mills and the largest steel plant in the world, with annual production of over 2 million tons of steel.

One of the most bizarre incidents in U.S. labor and industrial history occurred on Saturday, July 23, 1892, when a Russian anarchist, Alexander Berkman, attempted to assassinate Frick. While Frick was conferring with Carnegie Vice President John Leishman, Berkman burst into the office and fired a bullet that penetrated Frick’s neck and lodged in the middle of his back. Leishman grabbed Berkman, who then got off a second shot, this time finding its home in Frick’s neck. Berkman’s third shot missed its victim. Frick then recovered and grabbed Berkman. The two, along with Leishman, spun around the office in a macabre dance. Frick, suffering from loss of blood, pulled the others to the floor. A carpenter then entered the room and began beating Berkman on the head with a hammer. Berkman was a slight man, no bigger than Frick. Yet, despite three-on-one, and while being beaten on the head, Berkman managed to pull a stiletto out of his pocket and drive it into Frick’s back, hip, right side and left leg.

The police finally arrived, and Berkman was subdued. But he was not finished. He was chewing something—and it was not Wrigley’s spearmint. In his mouth was a capsule of fulminate of mercury, sufficient in strength to blow the entire building apart. Despite two bullets and four stab wounds, Frick maintained consciousness. When a doctor arrived and started to give Frick an anesthetic, he refused, preferring to guide the doctor toward the two imbedded bullets. Smiling wanly, he commented: “Don’t make it too bad, Doctor, for I must be at the office on Monday.” It took the doctor two hours to locate and extract the two bullets, and then Frick returned to his work where he left off. He remained at it an hour or so, as if he had only dozed off and had a bad dream. Ernest Hemingway had a phrase for this kind of courage—“grace under pressure.” And Frick was universally lauded for his superhuman performance. Through no fault of its own, the Amalgamated lost much of its public support. Berkman’s bullet never found Frick’s heart, but it did penetrate the heart of the Homestead strike.

The Carnegie/Frick defeat of labor at Homestead cleared the way for spectacular profit growth, from under $2 million in 1893 to almost $40 million in 1900. The reputations of both men were damaged by the strike—Carnegie’s more than Frick’s. As the success of the company and the size of the Carnegie fortune advanced in tandem, Carnegie was of two minds. He recognized and valued Frick’s exceptional capabilities, but he resented Frick’s growing reputation and the power he had so willingly delegated to the Carnegie chairman.

During 1893 and 1894, Carnegie increased his meddling in Frick’s management of the steel and coke companies. When Frick sought to purchase a portion of Henry Oliver’s Mesabi ore properties, Carnegie opposed it: “Oliver’s ore bargain is just like him—nothing in it…” Frick forged ahead anyway, and eventually extended their ore holdings with leases from John D. Rockefeller. Perennial violence in the coal fields again flared, resulting in the murder of J.H. Paddock, the chief engineer of the coke company. Carnegie, writing from Scotland, was unsympathetic. During competitive bidding for a Russian armor contract, Carnegie disclosed the bid price and lost the business to Bethlehem Steel. The straw that broke the camel’s back, however, was Carnegie’s decision to merge the works of independent coal operator W.S. Rainey into H.C. Frick Coke. Frick was not consulted, and resigned in December 1894.

As he usually did, Carnegie backpedaled, but this time to no avail. John G.A. Leishman was made president and, through the intervention of Phipps, Frick agreed to take the position of non-executive chairman. For two years this arrangement worked well. Leishman handled the day-to-day activities and most of the interface with Carnegie, while Frick continued to call all the major shots. But after two years, Leishman made some indiscreet personal investments, and in March of 1897 was replaced by Charles Schwab. Frick facilitated this switch, and for him it was an improvement over the arrangement with Leishman. Schwab was an incomparably better manager than Leishman and was destined to succeed Frick as the full-fledged CEO of Carnegie Steel. Schwab was young (35), and Frick had brought him along every step of the way. “Smiling Charlie,” as he was known, had other talents that served both himself and the enterprise. He had superb political skills and mediated between the prickly Frick and the mercurial Carnegie as nobody else could.

As both Frick and Carnegie grew increasingly comfortable with Schwab’s leadership of Carnegie Steel, the day of Frick’s permanent exit grew closer. The fatal year was 1899. Carnegie indicated by vague language, as always, that he was amenable to a buyout. He granted Frick and Phipps an option for $1,170,000.

The final break occurred over coke prices. Carnegie insisted upon a price of $1.35 per ton, while Frick moved prices steadily up as the market strengthened to $1.75 a ton. Two reasonable men could have settled on a middle figure, but Frick and Carnegie had no desire to be reasonable. They shared a mutual desire to be rid of one another. On Dec. 5, 1899, Carnegie called for Frick’s resignation at a board meeting in Pittsburgh. Without a fuss Frick resigned. But Carnegie was not through. Having stripped Frick of his power, he then attempted to deprive him of the better part of his wealth.

Carnegie’s weapon of choice was the “iron clad agreement.” This was the brainchild of Phipps, and was drafted in 1877, shortly after the death of Tom Carnegie. It provided that a partner’s share could be purchased at book value (far below the fair market value) from his estate with payments over time. This was designed to prevent a forced liquidation of the company. A second clause of particular importance to the Frick/Carnegie struggle provided that a partner could be forced to sell his shares back to the company at book value upon a 75 percent vote of the shareholders. Carnegie got the required signatures, and Frick was offered $5 million for his shares. On Carnegie’s part it was an unconscionable act. Frick threatened to sue, making public the fantastic profitability of Carnegie Steel. The consequences could have been dire. With the intercession again of Phipps (who, to his credit, refused to vote with Carnegie) and other mutual friends, Carnegie backed down. Frick walked away with a nice step up to $31 million ($620 million in today’s money). Things only got better for Frick in 1901, upon the sale of Carnegie Steel to the newly formed, Morgan-backed, United States Steel Corporation. Frick’s holdings were valued at $61.4 million ($1.23 billion).

At the time of the formation of U.S. Steel in 1901, Frick was 52 and at the height of his powers. Had he been asked to run the giant corporation he would doubtless have done so, but the call never came—Carnegie may have had something to do with it. Frick did serve as a director and member of the powerful finance committee until his death in 1919. Elbert H. Gary, U.S. Steel’s longstanding chairman, said of Frick: “He spoke little… and said much.” After his move to New York in 1902, Frick left behind a career as an industrial manager and assumed the mantle of a national finance capitalist of the first rank. He became a director of National City Bank, Equitable Life Assurance Company, and several other major corporations. Even more important were his ties to the major railroads. He was a director of the Chicago and Northwestern, Union Pacific, Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe, B&O, Norfolk Western and the fabled Pennsylvania. He had, at one time or another, $6 million invested in each of these roads.

Frick did not forget about Pittsburgh. In 1899, he joined A.W. Mellon in the formation of the Union Trust Company, and in 1902 joined the board of Mellon National Bank, the successor to T. Mellon & Sons. By 1906, Frick was the largest property holder in Pittsburgh. His two signature developments in downtown Pittsburgh still grace Grant Street: the Frick Building and the William Penn Hotel.

Since the age of 30, Frick had been collecting art. With somewhat more time and a great deal more money after 1901, he set about building one of the nation’s great and enduring collections. In 1914 he completed a 60-room mansion at Fifth Avenue and 70th Street in Manhattan. It was designed to serve as a permanent repository for the Frick Art Collection. At his death it held works by El Greco, Gainsborough, Goya, Hals, Millet, Monet, Rembrandt, Rubens, Turner, Velasquez, Van Dyck, Veronese and Whistler.

Frick died in 1919, at the age of 70, four months after his partner and nemesis Carnegie. He left an estate of $145 million ($2.9 billion in today’s money). Most of that—about $117 million—was directed toward charitable good works. Art valued at $50 million, plus a $15 million endowment, went to establish a museum open to the public at One 70th Street. Some $15 million went to Princeton (where his son Childs was educated), and $5 million apiece went to Harvard and MIT. Pittsburgh received the 151-acre Frick Park and later bequests through his daughter Helen. Money also went to the coke region.

Frick is not an easy man to come to terms with. Beyond doubt, he is a seminal figure in the emergence of the steel industry, and, indeed, industrial America. Within steel, he stands second only to Carnegie, and one can easily give him pre-eminence by arguing that Carnegie was not a steel man but a financier and promoter without parallel.

His charitable endeavors merit the highest praise. At $117 million ($2.34 billion), they dwarf those of Heinz and Westinghouse, and as a percentage of his estate, they exceed the bequests of his friend A.W. Mellon. Andrew Carnegie was a beloved figure; he worked at it. He never missed an opportunity at every stage of his career to burnish his reputation and place in history. Frick did not. If we were to ask his doppelganger why not, we might hear an echo of Clark Gable’s last line in “Gone With the Wind”: “Frankly… I don’t give a damn.”