In mid-November, when daylight dwindles, the sky turns flannel gray and a cold drizzle waterboards Pittsburgh, I flap my old, arthritic wings and fly south to Florida—God’s waiting room.

Upon arrival, I encounter nice people who inquire where I am from and, upon learning the answer, chirp brightly, “You must be a Steelers fan!”

Good guess. Most every male adult from western Pennsylvania is a Steelers fan. The stranger might as well have said, “You must shop at Giant Eagle!” But what would he or she have employed as a follow-up, assuming I had agreed? “How about those weekly specials?”

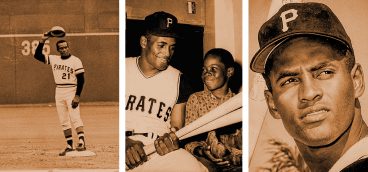

Assuming that I am a Steeler fan makes for a low-risk conversational gambit. But it so happens that I am not a fan of the Steelers, Pirates or Penguins; not a fan of Pitt, Penn State or Duquesne sports teams because I have been paid to observe them with some semblance of objectivity, if not with a jaundiced eye, for the past 30 years.

I did root for Richie Ashburn, Robin Roberts, Curt Simmons, Andy Seminick, the careless lothario Eddie Waitkus, and the rest of the whiz kids of the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies. But the Yankees swept the World Series from the Phillies that fall. The winners, it turned out, had fewer kids but better whiz. At 13, I made a pact with the Devil (who played a fiddle and looked like George Steinbrenner): I traded my team allegiances for a press card.

A fan is someone who makes an emotional investment in the fortunes of the team he or she follows. That’s not part of my job description. In my salad days as a sports writer, I was quoted in Esquire magazine as saying I would start rooting for the success of the team I was assigned to cover when its players began showing up in the press box and cheering for me to write a good story. It still hasn’t happened.

As a fellow columnist once explained to an outraged athlete, “When you lose, my job is to make fun of you. When you win, my job is to make fun of the other team.”

So I am not a fan. I’ve spent a lot of time around fans, though, observing and attempting to understand them. I am, in fact, a fan of Pittsburgh sports fans. I study them in the hope of finding the truth beneath the clichés that surround them.

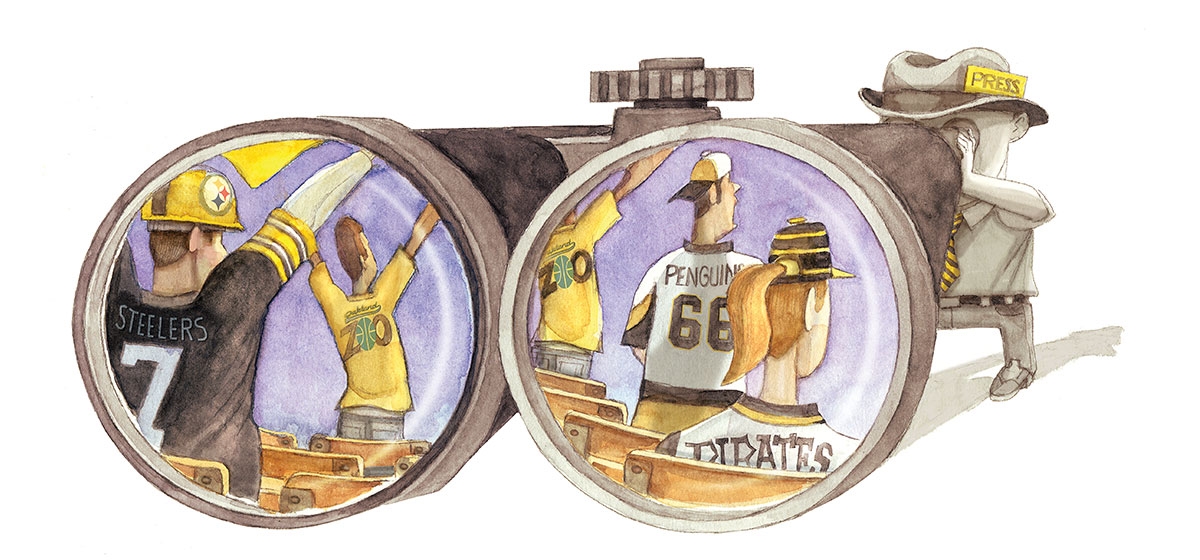

Let’s define our terms. When we talk about fans do we mean season-ticket holders? People who attend games occasionally? Do fans include people who never go to games, but dress up in black and gold upon occasion and wear “Go Steelers” corsages on their blouses? Can one be a Steelers fan if he or she thinks Jerome Bettis still starts at tailback? Can one be a Penguins fan without knowing Sergei Gonchar from Alexander Pushkin?

How about this: A fan is anyone who identifies himself or herself as such.

A poll commissioned by another Pittsburgh sports franchise found recently that a majority of those Pittsburghers who identified themselves as Steelers fans never had seen the team play in person. A majority of those polled knew the Steelers had reached the playoffs the previous winter. They hadn’t, by the way.

From a marketing standpoint, that is a good thing. From a marketing standpoint, what every team strives to be is a “brand.”

The Steelers are a brand in western Pennsylvania. People who never have seen them play a down at Heinz Field line up to buy licensed Steelers merchandise—jerseys, caps, can openers, you name it. Advertisers, lured in part by luxury-box tickets and free trips to road games, pay premium rates to be the official dog walkers of the Steelers. Star players come and go; the brand remains.

Brand loyalty translates to dollars. The Cubs are a brand; the Pirates are not. The Steelers are Proctor & Gamble. The Penguins, thanks to shrewd marketing, have become a brand in recent years.

Hockey in Pittsburgh was a cult sport until the Penguins drafted Mario Lemiuex in 1984. If there were 11,000 fans in the arena for a Pens game, there were 11,002 Pittsburghers who cared how the game turned out. Hockey fans in Pittsburgh, as elsewhere, once answered to “cement heads.” They had a reputation for putting the “duh” in duh-mb.

Not anymore. It is fashionable now to follow the Penguins. Their fans are younger and hipper than Steelers or Pirates fans. Thousands of (mostly young) Penguins fans now set up camp to watch a giant-screen TV outside the Arena when home games are sold out. Thousands of high school and college students, members of the Penguins’ Student Rush Program, wait in line to buy tickets at cut-rate prices when games are not sold out.

One night, a van pulled up to the front of the student rush line. Out leaped several Penguins players, bearing pizzas. It wasn’t the front office’s idea. The players thought of it—and paid for it—themselves. Now they show up once a season to pass out items of apparel from American Eagle, the official sponsor of the student rush. The chain has even developed a Student Rush line of youth-oriented clothes.

Penguin fans once had a well justified reputation for rowdiness. No more. Once in a while, when the Flyers or the Maple Leafs come to town, they bring with them a group of well lubricated fans eager to prove their loyalty with their fists. Almost invariably, the locals oblige them. Other than that, Penguins crowds are enthusiastic but well behaved.

One of the reasons the Penguins survived and flourished in Pittsburgh is Mark Madden. First on WEAE-AM and then on WXDX-FM, the station that broadcasts Penguins games, Madden, who is 49, has pitched himself successfully to males 18 to 35. His passion for hockey and his success in attracting listeners within that demographic are one big reason that Penguins fans skew younger now than they did a generation ago.

The Penguins attract more attention on Facebook and more traffic on Twitter than any other National Hockey League team. Their local TV ratings (a 6.9 last season on average) are the second highest among U.S.-based NHL clubs. Forbes magazine recently named the franchise the NHL’s fastest growing brand.

The Penguins could sell out every home game if they wished to do so. Instead, the franchise caps full season-ticket packages at 14,000, almost 3,000 below capacity, because it strives for a certain amount of turnover.

The Pirates sell out annually on opening day and seldom thereafter. They now sell somewhere south of 10,000 season tickets (management refuses to make the number public). But they too understand the importance of churning ticket-buyers.

“What we’d really like to do,” a Pirates marketing executive confided, “is have a ticket base of a million fans, each of whom attended three games a year.”

In reality, Pirates ticket-buyers attend four games a season on average. But there are not a million of them. Not even close. It has become fashionable after almost two decades of incessant losing, to refer to “Pirates fan” as an oxymoron.

“Do the Pirates really have any fans?” the pundits ask, “or is it bobblehead promotions that create the illusion of baseball interest in town?”

True, the Pirates drew only 1,577,853 last year, their 17th consecutive losing season. But they won only 62 games. That comes to 25,460 tickets sold per victory. Not great by National League standards; the division-winning Los Angeles Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies and St. Louis Cardinals each sold 40,000-plus tickets per win. But they draw from far larger population bases than do the Pirates. The Cincinnati Reds, who won 78 games, drew 1,747,919. That comes to an average of only 21,759 a win.

The Pirates fans are out there, dormant, awaiting their time, should it ever come. The proof is in the team’s local TV ratings, which were up 17 percent last year.

The Steelers are not a growing brand; they are full grown. Six National Football League championships have elevated them to iconic status. Their games at Heinz Field are sold out without exception. Their fans are loud, loyal and ubiquitous. It takes roadblocks to keep them away from training camp practices. Even at road games, they show up by the thousands, waving their Terrible Towels.

What the network announcers don’t tell you is that those rooting sections are in large measure a byproduct of the blue-collar exodus from Pittsburgh that started when the steel mills began shutting down. The departing Steeler fans took their loyalties along with them and found each other at sports bars all over America. A Steelers marketing executive estimates there are 750 such bars scattered across the United States, where Steelers games are the featured entertainment on giant-screen screens on weekends during the season. When the Steelers come to town, the patrons of those bars buy tickets from sources in their new cities and show up at the stadium in towel-waving droves.

Thousands who stayed behind have maintained a Steelers tradition: tailgating. The NFL has asked its teams to limit pregame parking-lot partying to three hours, but a few franchises declined to go along. The Steelers open their parking lots five hours before game time, and the beer begins flowing shortly after the first tailgater arrives.

Given the foamy state in which some tailgaters finally take their seats, it is remarkable that only about 10 incidents requiring the attention of security guards unfold at Sunday afternoon games with 1 p.m. starting times. The later the starting time, the more time the tailgaters have to imbibe their pre-game refreshments. Monday night games result in an average of 20 incidents in which security guards are forced to intervene.

The vast majority of fans at Steelers and Pirates games show up sober and stay that way. They are, at least by my observation, far more tolerant of out-of-town fans wearing the visiting team’s regalia than their counterparts in Philadelphia, New York and Oakland. San Francisco 49ers fans who had the temerity to show up at a game against the Eagles in Philadelphia last December were pelted with snowballs for their trouble. Then again, Philadelphians once heaped the same snowy abuse on Santa Claus.

Duquesne University basketball was a brand once, before sports teams were thought of in those terms. Over the course of almost half a century, however, the school’s administration demonstrated a dazzling lack of commitment to its men’s basketball program, and its fan base melted away. By the time the Dukes hit bottom, winning three games and losing 24 in 2005–06, it seemed there was no one left to care.

Duquesne hired Ron Everhart as its coach four years ago, and took a step up —from embarrassment to mediocrity. When the Dukes went to the National Invitation Tournament last year, it was their first postseason appearance since 1994. But will the program regain the dedicated fan base it enjoyed in the 1950s? Maybe. But probably not under the present deity.

The newest sports brand in town—Pitt basketball—gets my vote for the most-improved fans of the decade. I’m referring here to one group of Pitt basketball fans in particular: the Oakland Zoo.

For those who do not know, the zoo is the student section at the Petersen Events Center, where the Panthers wage basketball. The name of the group and their courtside seats are a carryover from Petersen’s predecessor, Fitzgerald Field House. But the new Oakland Zoo, to its credit, bears little resemblance to its predecessors.

The old zoo was a motley collection of potty-mouthed schoolboys intent upon intimidating visiting teams. They were a disgrace to their university and to college athletics. It speaks well of the coaches and players who visited Fitzgerald Field House that none of them ever reacted to the abuse by climbing into the stands and doing a Ron Artest.

The transformation began during the coaching tenure (and at the instigation) of Ben Howland and has continued under Howland’s successor, Jamie Dixon. The new zoo is PG-rated and highly creative. Readily identifiable by its gold jerseys, the zoo may not be quite as clever as Duke University’s Cameron Crazies, but neither is anyone else.

There are 1,500 courtside seats reserved for the zoo at “the Pete,” and there is never an empty seat. The overflow sits near the rafters of the arena, which seats a total of 12,508.

In addition to making Pitt’s games more fun, zoo members also take part in a variety of charitable and civic works. If they are the sports fans of Pittsburgh’s future, then our sports future is in good hands. As to the present, I think Pittsburgh sports fans in general are vastly underra-ted. Yes, I know the Pirates didn’t sell out Three Rivers Stadium for a handful of playoff games back in the Barry Bonds era. Nobody ever blamed the city fathers for putting their baseball team in a 60,000-seat monstrosity. It was the city’s fans who took the heat.

Well, I have news for you: Pittsburgh sports fans are the best I have seen, and I’ve seen a lot of them. If I turn out to be a sports fan in my next life, I hope I am wearing black and gold.