Wanted: More Workers (Part III)

With baby boomers poised to retire and far fewer younger, skilled people available to replace them, the region faces a potentially crippling workforce gap that could be especially damaging in sectors that require STEM (science, technology, engineering math) skills. The Allegheny Conference on Community Development estimates that the gap could reach 144,000 workers, although that’s probably more theoretical than a likely scenario. Nevertheless, businesses, workforce development organizations and educational institutions are taking action to avert or narrow the workforce gap, largely along two tracks. Some initiatives aim to change the mindset about technical careers as well as the methods of teaching STEM skills. This final installment of our series on the workforce gap looks at three entities trying to plug the gap now.

***

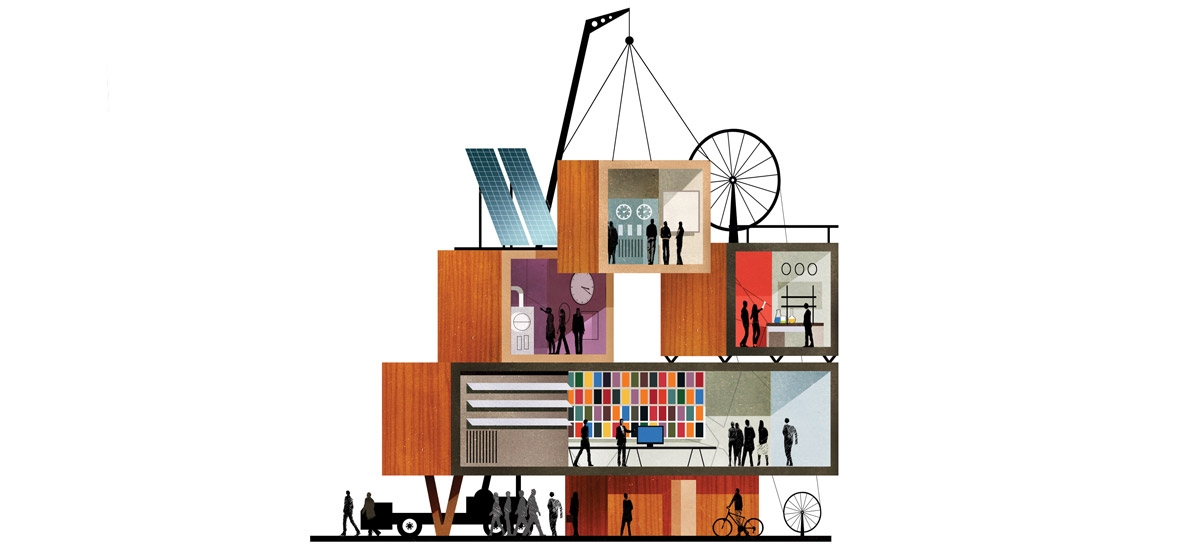

The Energy Innovation Center (eic) in Pittsburgh’s Hill District is not your typical workforce development site. Rather, it may be the epicenter of energy. The building boasts more than a dozen sustainable energy source systems to power it, including solar, microturbine, combined heat and power and an ice farm. Soon, these will be complemented by geothermal and windmill systems.

The goal, of course, is not to provide different climates within the structure. Rather, it’s to enable EIC to function as a working classroom for students training for jobs in energy fields.

“We built classrooms around our operating equipment,” says Robert A. Meeder, president and CEO of Pittsburgh Gateways Corp., which bought the former Connelly Trade School property in 2011 and converted it to EIC. “It’s a campus where the operating systems can teach the science, math and technological processes that are critical needs in the workforce.”

Energy is what Meeder calls EIC’s “sweet spot,” but it’s not the only sector for which students are preparing. EIC has eight gardens on site to provide training in horticulture. It’s building a kitchen to provide instruction in careers involving nutrition and high-volume food production. It has customized several training programs for roofing companies, and it has implemented a training program with Eaton at the company’s Cranberry location. In all, EIC is introducing students to 31 careers.

To support its programs, EIC has partnered with many businesses in the region as well as nine unions; some provide cash contributions while others donate equipment. The facility features products and processes from 132 companies, and the equipment isn’t worn or outmoded. Donors often bring potential customers to EIC to view company products in action. Says Meeder: “The trades themselves are trying to eliminate the concept of trades as ‘Track B,’ a second option. We’re trying to eliminate many of the stereotypes of these careers as cluttered, dirty and greasy. We’ve wrapped these trades around images of success.”

Most EIC students are what Meeder calls “unemployed or under-employed.” To identify and recruit them, EIC collaborates with such community-based organizations as Hill House Association, YouthPlaces, Adonai Center, the Pittsburgh Promise and Holy Family Institute.

“They know their constituencies,” Meeder says. “They can do the vetting and assessing and can help with other obstacles in their lives that can keep them from the work site.”

EIC’s goal is to provide enough newly trained, skilled workers to fill 120 jobs within the next year and increase that number in the future.

“We’re supporting sustainable careers with sustainable wages,” Meeder says, “and we want students to have a number of options to apply their skills on different occupational tracks. We’d like to see wages of $12 per hour and up so they can sustain their careers and not have to do four other things to make a living.”

Classroom instruction/lab training/externships

A number of the region’s most successful and enduring STEM training programs originated when industry, which perceived the ramifications of the potential workforce gap early, sent out an S.O.S. to the educational community. Such is the case with Bidwell Training Center’s Chemical Laboratory Technician major, which Bidwell introduced in the early 1990s.

“About 13 chemical companies approached us about developing a program to free chemists from rudimentary-type responsibilities they had on a daily basis,” says Valerie Njie, the center’s executive director and vice president. “Our first instructor, who was employed by PPG and loaned to us, had been a professor at Howard University. He was an experienced instructor. That’s why the program ran so smoothly.”

“The trades themselves are trying to eliminate the concept of trades as ‘track b,’ a second option. We’re trying to eliminate many of the stereotypes of these careers as cluttered, dirty and greasy.”

— Robert A. Meeder, president & CEO, Pittsburgh Gateways Corp.

Now, Bidwell, a unit of Manchester Bidwell Corp., has a full complement of full-time instructors who lead students through a rigorous 52-week program that’s part of their work towards associate degrees. Beyond classroom instruction and lab training on campus, students must complete eight-week externships with local employers.

“The externship is an actual training experience,” says Karen Johnson, director of the program. “They can’t just shadow someone. They have to be working in a lab. We train them with a broad set of skills transferrable to any lab. During their externships, they get hands-on experience in more specific areas.”

The state picks up tuition for program students, who represent a demographic mix—some just out of high school, others displaced workers seeking retraining.

“Our students are from Pittsburgh, but we also have students from Beaver, Washington and Butler counties,” notes Njie. “With our current state funding, there are no restrictions on the types of students we admit. What we have to determine is whether an individual is committed to the program.”

The major features two cohorts yearly, each with an average of 10 to 20 students. Multiply that by 25 years, factor in the program’s job placement rate of better than 70 percent, and you can see that Bidwell’s impact has been significant—a conclusion shared by the companies, including NOVA Chemicals, that have hired program graduates.

“The graduates of Bidwell Training Center fill a gap in today’s emerging workforce through the chemical laboratory technician program,” says John Feraco, director, expandable styrenics, for NOVA. “Over the years, we’ve hired three graduates of the program in entry-level positions. The training they received helped prepare them for the workforce, with technical proficiency, a strong commitment to safety and a solid work ethic.”

An unusual long-term goal

New Century Careers has been attacking the workforce gap for longer than most people have been thinking about it. It was formed in the late 1990s when 17 manufacturers put their heads together on developing trained employees they urgently needed to stay competitive. Recalls Paul Anselmo, co-founder and president of the South Side organization: “We knew we could never raise enough money to change the mind-set of the broader population about manufacturing careers, but we could change the mind of one person at a time and call him or her to action. I think we’ve made some impact.”

That impact comes from three related programs. The first, called Manufacturing 2000 (M2K), might be thought of as the entry-level division, for which New Century works with community-based organizations to identify and attract those whose job prospects may seem limited. The younger they are, the better.

“…we could never raise enough money to change the mind-set of the broader population about manufacturing careers, but we could change the mind of one person at a time and call them to action. I think we’ve made some impact.”

— Paul Anselmo, co-founder & president, New Century Careers

“One of my new goals is to try to target more high school-aged people,” Anselmo says. “Until they’re serious about what they want to do, they can bounce around a lot. If they could get engaged earlier in work with opportunities for advancement, training and education along the way, they won’t have lost those productive years.” New Century provides M2K training at no charge to students.

Many M2K grads advance to the pre-apprenticeship program, a collaboration between New Century and 61 companies throughout the region, most of them small-to-mid-sized machine shops and tool-and-die companies. This second component features on-the-job training and classroom instruction, much of it funded by employers. This year’s class includes 183 apprentices.

But what happens to those inexperienced workers when they join the workforce and are inundated by the demands for new skills in an ever-changing environment? That’s where the third element comes in. It’s called Manufacturing 2000 Plus (M2K+), and it features on-the-job training to enable employees to keep their skills current and develop specialties.

“Once a person leaves Manufacturing 2000, there’s so much more to learn,” Anselmo observes. “Some are still in training because that’s the way the industry is. Manufacturing embraces technology more than any other sector.”

Most ongoing training occurs on the job, but for some specialties, such as blueprint reading, geometric dimensioning and tolerancing, workers also attend Saturday classes. Personnel from the National Institute for Metalworking Skills provide the classroom instruction, although a new thrust of the program is “training the trainer,” that is, teaching more experienced workers to mentor their younger colleagues.

New Century relies on partnerships with manufacturers and funding from foundations, corporations such as Kennametal and Alcoa, and nonprofits including Goodwill Industries and the United Way. Its mission is expensive, although not as costly as it used to be. In 1999, when it rolled out a direct-response marketing campaign to attract students, the cost per enrollee was about $800. Now, because it has been successful and enjoys strong word-of-mouth, New Century’s monthly recruitment budget is $25; that princely sum buys an ad on Craigslist.

Anselmo estimates that several thousand people have advanced through New Century’s programs to manufacturing careers, but that’s nowhere near his ultimate objective:

“My long-term goal is to go out of business because we’re not needed anymore.”