Face the Facts About a “Multipolar” World

“It is simply a myth that the world is anywhere close to multipolar.” — Jo Inge Bekkevold, Norwegian Institute for Defense Studies

Previously in this series: Europe’s Shrinking Relevance

Why is it that so many commentators insist that we live in a multipolar world?

Part of it is simply ideological blindness. The university community, like it or not, is dominated by ideologues who are excruciatingly aware of America’s acknowledged faults and blissfully ignorant of its many virtues. They simply can’t stomach the idea that the US has no peers – and so they invent peers. China and the EU, of course, but we’ve dispensed with them. How about India, Russia, Brazil, South Africa, which are often mentioned?

The combined GDP of those five countries is a mere $8 trillion, one-third that of the US. None has a military that is capable of projecting power beyond their own backyards. Several are close to being failed states (Russia and South Africa).

Multipolarists often stoop to the risible. Here is Emma Ashford in Foreign Policy, offering as “poles” Ukraine and India: “The middle powers are becoming more influential. Consider just the last few weeks: Ukraine stepped up its counteroffensive against its much larger neighbor; India played host to the world’s biggest economies at the G-20.”

Ukraine might be a brave country but it is one of the poorest societies in Europe. And as for India, the presidency of the G-20 rotates – it was simply India’s turn to host the G-20.

And here is how Michael Kimmage and Hanna Notte began a recent article in Foreign Affairs: “Today’s great powers – China, Europe, Russia, and the United States …” We’ve dealt with China and Europe – the former has a military capable of projecting power only a few hundred miles around its own borders (China’s navy is no match even for Japan’s), while the latter has no military at all. What are these people thinking? Well, that’s the problem – they aren’t.

In academia and the think-tank world, multipolarity has been so dumbed-down that by their definition there was never a unipolar moment in the history of the world. Even during the height of the Roman Empire, after all, there was Carthage, Macedonia, Persia, Constantinople, and the many “barbarians,” just to name a few.

As for Russia, its economy is roughly the size of Italy’s (and Italy is nobody’s idea of a global pole), its citizens used to be affluent enough to just make it into the World Bank’s “developed country” category but have now slipped back into “undeveloped,” and its country and leader, Putin, are increasingly isolated and despised.

Mutipolarists often argue that, while it may be true that no country approaches the US in economic or military might, the rest of the world is catching up fast. Certainly it’s true that the US share of the global economy is lower than it was just after World War II or just after the collapse of the USSR, but those were hardly ordinary times.

But notice, first, that to the extent that other countries have grown richer and stronger, it’s precisely because of US policies – especially serving as the world’s policeman, insuring that global trade can proceed in peace. And notice, second, that the idea that the rest of the world is catching up to the US is wildly exaggerated: the US share of the global economy is, today, less than 1% smaller than it was a decade ago.

And in the realm of finance – the engine of economic growth – the US has nothing approaching a peer. The US dollar reigns supreme, accounting for one leg of almost 90% of FX – currency – transactions, and as Robert Armstrong put it in the Financial Times, “In the realms of finance and markets, the world is as unipolar as ever and possibly more so.”

Finally, we need to recognize that, should the world actually become multipolar we will all assuredly regret it. Multipolarity was the universal reality in the world for two centuries before 1945 and those were the two most warlike centuries in many centuries. We don’t want a unipolar world with the likes of China as the hegemon and we don’t want multipolarity under any circumstances. Let’s be thankful for what we have.

The issue of polarity isn’t merely an academic argument – it’s not like counting how many global poles can dance on the head of a pin. It matters a lot whether the world is multipolar, bipolar, or unipolar. If Russia is, in fact, a great power, as Kimmage and Notte would have us believe, then Russia is a confident nation that can hold its head high and deal rationally with other countries.

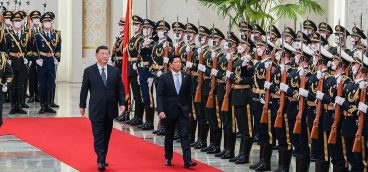

But if – as is the case – Russia is no pole at all and is in fact a rapidly declining society, then Russia is a much more dangerous player on the world stage and has to be treated as such. And the same is true of China – if the country is growing rapidly and the CCP is secure in its power, as was the case until about a decade ago, then China will also be a more or less constructive player on the world stage.

But if China is a power in economic, military, and demographic decline, it is a dangerous beast and will need to be dealt with as such. And that is exactly what China is: at its peak China’s economy was 75% as large as that of the US – today it is 64% as large.

Which brings us to the final reason that polarity matters. As globalization slows, then reverses into deglobalization, the world’s countries will be mainly on their own. Those countries that rode the wave of globalization successfully for decades, but which failed to evolve away from an export-led, capital-intensive economy toward a consumer-led economy, will wither.

I’ll comment on that near-dystopian world early next year.

Next up: The Oxford Companion