Europe’s Shrinking Relevance

“As a result of the accelerating decline in Europe’s global influence and reach … the overrepresentation of Europeans in global institutions is the greatest flaw in the international architecture.”Walter Russell Mead

Previously in this series: Failing to Get Rich Before They Get too Old

“The EU is a construct perfectly adept at standardizing phone chargers … but one that [otherwise] scarcely matters.” The Economist

“The deep truth underlying [Europe’s many] colliding anxieties is that Europe is powerless.” Philip Stephens in the Financial Times

The decline of “core Europe” – for centuries the dominant societies in the world – has been breathtakingly decisive. Germany, France, the UK, Italy and Spain are now pygmies compared to the US and China and even compared to India – today only Germany is larger than India economically, but that will change during this decade. (On a purchasing power parity basis, India’s economy is already larger than Germany’s.)

The German economy sits at $4 trillion, compared to $27 trillion for the US and $19 trillion for China. Core Europe is economically so small that if California were a European state it would be the second largest economy on the Continent, just behind Germany.

Europe’s decline has been somewhat disguised by the advent and subsequent expansion of the European Union, which now includes 27 sovereign nations with an aggregate GDP of nearly $17 trillion (in other words, close to that of China) and a population of nearly 450 million – far larger than that of the US.

The EU has been a remarkable accomplishment, far more successful than even its biggest boosters could have imagined. But as an aspiring “pole” in a multipolar world it leaves much to be desired. In the first place, the EU is obviously not a sovereign nation at all but a wonky aggregation of them. In practice the EU is successful internally but virtually non-existent externally.

The EU has no foreign policy (and no power to direct the foreign policies of its members), no military force (the defense of Europe is handled by NATO, i.e., the US), and little control over the economic policies of its members. Just recently Josep Borrell, the EU’s chief diplomat, was reduced to insisting that China take the EU seriously as a geopolitical power, arguing that “the war in Ukraine has converted [the EU] into a geopolitical power, not just an economic one.”

Of course, what Russia’s invasion of Ukraine actually showed was the utter impotence of the EU in every sense and its complete dependence on NATO – that is, the US.

As though all that wasn’t bad enough, the center of gravity of the EU has gradually moved eastward as new members have joined and as those new members’ economies have proved more dynamic than those of “core” Europe.

Unfortunately, many of the most important new members of the EU don’t share the liberal values of “core” Europe, so much so that the European Parliament has declared (for example) that Hungary, a member nation, “is no longer a democracy.” When Ukraine inevitably joins the EU, the center of gravity will shift even further east. Ukraine is the largest country in Europe geographically and its GDP will put it in sixth place in the EU even though it is also extremely poor.

Finally, while the aggregate GDP of the EU is indeed impressive, the average GDP of EU member states is a mere $630 billion – i.e., about 2% of US GDP. And, as noted above, the largest economy in the EU – Germany – is barely larger than that of California.

On a per capita basis, the EU produces $40,000 of GDP versus $80,000 for the US. In other words, the productivity of the US vastly outstrips that of the EU, resulting in much faster economic growth in America, ensuring that its dominance over the EU will only increase. Even the EU’s most productive economy, Germany, produces per capita GDP of only $51,000.

Interestingly, while most American observers continue myopically to assume a multipolar world, investors – who have to put their money where their mouths are – are under no such illusions. Recently my company (Greycourt, that is, my day job) published a paper digging into the question of why the EAFE Index is so chronically undervalued relative to the S&P 500. (White Paper No 70 – Apples and Oranges, available at https://www.greycourt.com/trending/greycourt-white-paper-no-70-apples-oranges/.)

For those of you who don’t stare at stock prices all day, the EAFE is an index of large companies domesticated mainly in Europe and Japan, while the S&P 500 is an index of large companies in the US. The US stock market is more than twice as large as all the markets in the EU put together.

The paper makes several points but among its main conclusions are these:

In general, investors are unwilling to pay anywhere near as much for the EAFE as for the S&P. The forward P/E (price-to-earnings ratio) of the S&P is 50% higher than the forward P/E of the EAFE.

The S&P is heavily weighted towards the economy of the future, while the EAFE is heavily weighted toward the economy of the past. Information Technology makes up 30% of the S&P versus 7% for the EAFE, while Industrials make up 15% of the EAFE versus 8% for the S&P. (As of 7/26/2023)

Every sector of the S&P commands a higher valuation than its corresponding sector in the EAFE. In short, investors view the EAFE as a “value” investment, that is, companies with slower growth prospects that command lower valuations, while the S&P is viewed as a “growth” investment, that is, companies with high growth prospects that command higher valuations.

Impressive as are the internal accomplishments of the EU, it can make no colorable case to be a rival to the US in a multipolar world – it simply isn’t a pole at all.

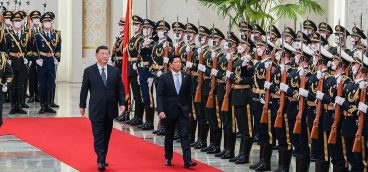

It seems obvious that China is in terminal decline, with no hope of renewed economic growth as long as President Xi remains in power – and possibly as long as the CCP remains in power. It also seems obvious that the EU isn’t, and never was, a great power in any sense except for the (largely-irrelevant) aggregate economic scale of its 27 members. So why do people insist that we live in a multipolar world? We’ll look at that issue next week.

Next up: The New World Order, Part 4