Close to Home: Local Poets Get Personal

If all politics is local, perhaps all good poetry might be considered local, as well. Consider how setting and description flavor the Homestead poems of Robert Gibb and the Detroit poems of Jim Daniels. In his seminal essay collection on poetic craft, “The Triggering Town,” poet Richard Hugo asks writers to ground their work, saying “The poem is always in your hometown…” When place becomes specific, it also becomes both universal and more personal.

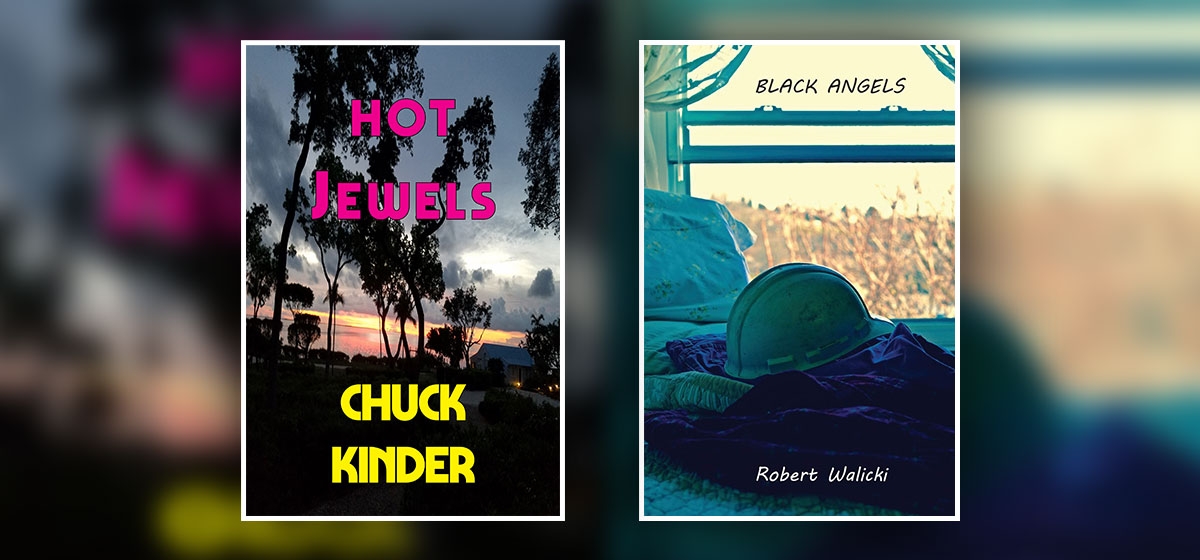

Chuck Kinder’s “Hot Jewels” and Robert Walicki’s “Black Angels,” two recent collections from Pittsburgh-based Six Gallery Press, try to do just that.

West Virginia-native Chuck Kinder, who passed in May at age 76, was remembered as much for his teaching and friendships with a wide range of renowned writers as for his own work. His novel, the Roman a’ clef, “Honeymooners: A Cautionary Tale,” focused on the adventures of two thinly-veiled versions of short-story master Raymond Carver, who Kinder met while both were Stegner Fellowship scholars at Stanford University in the early 1970s. Kinder went on to become a beloved writing professor at the University of Pittsburgh. He is the basis for the Grady Tripp character in Michael Chabon’s “Wonder Boys,” who was played wonderfully by Michael Douglas in the film version shot here in 1999. Parties thrown in his Squirrel Hill home with students, faculty and visiting authors rubbing elbows as they unwound are legendary.

Ostensibly, “Hot Jewels” travels wide in a bawdy reminiscence of the speaker’s life, who refers to himself as “an old blind poet,” or more pointedly as, “Charles Alfonso Trout Kinder.” It’s an affect that signals Kinder’s playfulness as the work throughout plays full of sentiment, yet seems to disregard craft. He jokingly summed up his aesthetic in a 2012 interview with the City of Asylum’s publication “Sampsonia Way,” stating the cause of the transition from fiction: “I don’t have the energy or concentration to do that anymore. So I’ve been writing poetry. I mean, how hard could it be? Throw a few lines of paragraph on the page, split it up. That’s a poem! So I’ve written two books of poetry since my stroke. (Laughs)” It is in this vein that “Hot Jewels,” Kinder’s final book, looks to be taken much as a goodbye as it is a work of art.

Many of the poems found in the book’s 147 pages are dedicated to writer friends, both living and dead, such as Carver, Hugo and Chabon. There is also work that recalls his West Virginia childhood; his brief foray into crime at age 17, from which the name of the collection is derived; and, most importantly, on his “True Love at the edge of the galaxy,” Diane Cecily, his wife of 40 years. The scope is often sprawling as his fiction could be and the dreamy, less-than-serious tone takes some getting used to. The collection is at its best when Pittsburgh gets center-stage. “Birds of Hammered Gold” works well with its Squirrel Hill Café—aka, “The Squirrel Cage”—setting, and appearances by local light-heavyweight hero Billy Conn and the much-missed Jimmy Cvetic are touching.

Six Gallery Press Editor Nathan Kukulski’s best move here might be his inclusion of “Bonus Features.” The section features standout local poets, such as Dave Newman and Scott Silsbe, dedicating new poems that stress the approachability Kinder maintained, unusual for someone of his literary stature.

The best of these tributes belongs to Trafford author Lori Jakiela. In “To Chuck Kinder Who Taught Me About Kindness,” she writes of her first published work in a less than prominent publication. The poem pivots to Jakiela’s machinist father, who supported her literary dreams, before she loops back to emphasize Kinder’s enthusiasm over this seemingly minor achievement. It ends with a visit to his celebrated home, of which she writes, “You, the great and magnificent writer/ I was too terrified to take a class with// opened your door to me and said, “POEM/ magazine, that’s fabulous!” and invited me in,// where I sat on a stool another/ of your students had painted for you.// On the seat was a nest full of eggs,/ like whoever sat on it// was hatching/ something wonderful.” While much of Kinder’s poetry in “Hot Jewels” could’ve used a heavier editorial hand, it remains a heartfelt sendoff for a man who clearly left his mark on multitudes—the greatest tribute any teacher can receive.

***

Walicki’s “Black Angels” seems cut from a more Modernist cloth. The poems lean on narrative, while relying on a voice that’s confident, yet sensitive to suffering and struggle. Walicki, a Verona resident who has long been a steady presence in Pittsburgh’s burgeoning poetry scene, recognizes the power and depth in daily life. The book’s emphasis is on the memory of experience and how those moments shape lives and he uses the book’s 114 pages to make sense of parental loss, bullying, blue-collar work and racism in highly readable ways.

Poems such as “What the Light Wants,” “Unseen” and “Trying It On” succeed because they’re willing to explore the aftermath of a father’s death through the tangible remnants of life. A favorite, “His Clothes,” is emblematic of this approach. “Afterwards, there was so much/ left, his dress shirt and brown slacks// knotted in a soft embrace,/ the caved in chest of a jacket,// twang of a hanger on a metal rod,/ an IV cart left behind in haste,” Walicki writes. It’s a scene that rings true in its description, yet never feels overwrought because of its plain-spokenness. The poem ends with a memory of a nurse’s shoe. “The wedge of a heel/ rubbed uneven, how she went back again// to see, because she didn’t/ believe, her own wrinkled palm// pressed against his bed, smoothing those new sheets down.” It’s a powerful image reminding readers of life’s fragility.

Musical reminders of adolescence also play a commanding role in the collection, operating as generational touchstone. Poems dedicated to Robert Smith, Prince and David Bowie will make connections with Gen-X’ers. However, it’s the inclusion of pieces such as, “B-Boy As Andromeda” and “B-Boy Meets Future Self” that find the mark with their attention to movement, as hip-hop introduced physicality in new musical ways for those of us coming of age in the early 1980’s. It also helped break down some racial boundaries, which many white-listeners may have been unaware of at the time.

Using Grandmaster Flash’s celebrated “The Message” as the title, Walicki explores overcoming Pittsburgh’s casual racism by writing “At ten, before any of us knew anything,/ we staged protests in the form of headstands,/ learning about racial equality in a Stanton heights basement.” This innocence is offset by adults fearful of “others,” summed up by a nun asking, “why I listen/ to that music and Don’t you know you’re white.” It’s a stunning yet unsurprising reaction to a music that often expresses the trials of everyday life for those dealing with economic disparity.

With Walicki’s “Black Angels” including a poem about a Mario Lemieux poster hanging in a New Kensington home and Kinder’s “Hot Jewels” celebrating a life of literary influence often made whole by Pittsburgh, local readers should feel close to home with these collections.