The City-County Building

Ask people their favorite downtown Pittsburgh building, and many will tell you Henry Hobson Richardson’s Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail. Pittsburgh’s first really famous piece of architecture has been popular consistently since its 1888 completion.

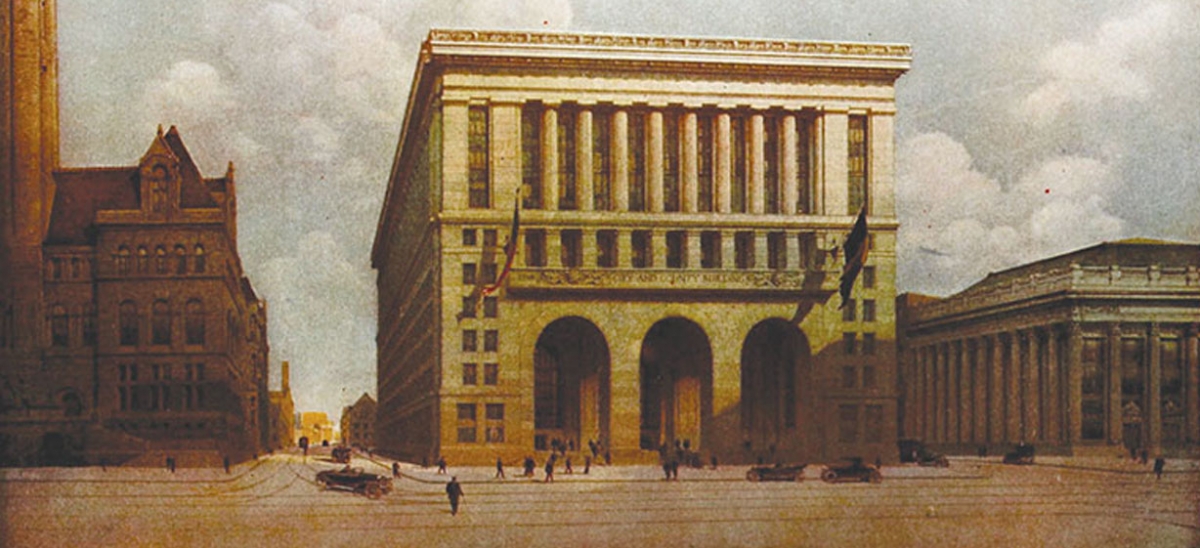

But the truly memorable public space is actually right next door, the City-County Building, completed in 1917. The soaring three-bay loggia, under roof but out of doors, is perfect for celebrations, farmer’s markets, or just chance meetings. And the inner corridor which is its majestic extension is “a golden hallway of columns,” says architect David Vater, emphasizing the effect of the gilt bronze.

Actually, the loggia is an adaptation of the medieval Loggia dei Lanci, Florence’s similarly three-arched public gathering pavilion. In Pittsburgh, the loggia is enlarged to fit American sensibilities and combined into the lower half of a brawny cubic office building. It is “grandly civic in its public spaces, yet at times almost modern in a no-nonsense way,” wrote historian Walter Kidney. The smooth pairing of historic and contemporary elements is typical of the creative approach of lead architect Henry Hornbostel. Says architect Daniel Willis, “the City-County building is at least as deserving of [praise] as its famous neighbor.”

Is it a shame that it hides in the shadow of Richardson, or does that simply enhance the pleasure of encountering it anew?

The soaring three-bay loggia, under roof but out of doors, is perfect for celebrations, farmer’s markets, or just change meetings.

It might have been otherwise. Hornbostel’s designs for Pittsburgh’s civic architecture begin as a tall tale in multiple respects. The need for courtrooms in the Richardson building increased rapidly very shortly after the building’s completion. Architect Frederick Osterling proposed adding a floor to the courthouse in 1904 (by removing the roof and rebuilding it with the additional floor in place), a suggestion that was roundly rejected. “The building cannot be changed without destroying its harmony and beauty,” said the Allegheny County Bar Association.

It was all the more surprising then, when Hornbostel suggested in 1907 that an enormous tower be constructed in the courtyard of the Courthouse, reaching to a height of 700 feet, which would have been the tallest office building in the world at that time. Latter day observers declared this object to be a joke. “A glori0us ‘stunt’ or an outrageous ‘attention getter’ ” said historian Jamie Van Trump, but Hornbostel was quite serious. He had proposed a similarly tall municipal office building for New York that was later built at a shorter height by a different architect. Hornbostel knew that high real estate costs meant that a tall, slender building could help pay for itself with savings in costs for land.

Allegheny County clearly already owned the space in the courtyard. The money saved in not buying a new site was up to $4 million, according to the Pittsburgh Sun, though Hornbostel seemed to be exaggerating that and other numbers. Still, in mid-April 1907, Hornbostel proposed his building to the County Council, which reacted positively, the Sun reported. But the scheme was shouted down in the court of public opinion, never to be considered again.

The idea that a civic building would combine traditional ceremonial government spaces in lower floors with an office high-rise emerging from the center had seemed outlandish in its first proposal. But Hornbostel realized it was too clever an idea to abandon. The architect reconstituted the same essential scheme, scaled it down and presented it as a competition entry in 1910 for the Oakland City Hall in California. With this design he won the commission to build the structure and completed his singular high-rise in 1914.

It was “the first American structure of this kind,” said architecture critic Aymar Embury, “and bound to attract a host of imitators.” Indeed, afterward, the city hall tower became a standard U.S. building typology for at least a couple of decades, embodied in structures such as the Los Angeles City Hall, the Buffalo City Hall, and, a little more loosely, the Nebraska State Capitol.

Oddly, Pittsburgh would get a Hornbostel City Hall, but not exactly a tower. The City and County eventually purchased expensive land at the 414 Grant St. site to build a shared building. With his success in Oakland, Hornbostel was a leading contender, and he won the competition as design principal with his firm Palmer, Hornbostel and Jones.

But he seemed more chastened by the failure of his first skyscraper proposal for Pittsburgh than he was encouraged by his success in Oakland. So his 10-story structure for Pittsburgh is massive, but resolutely shorter than Richardson’s courthouse. Subtly but unmistakably, Hornbostel placed a cornice line at the sixth floor of his structure to match a similar element on Richardson’s building in tribute.

With particularly plain and unornamented granite on its long walls, the City-County Building is in some ways an austere building. This was a passive rebuke of the corruption in cities nationwide that had led to huge cost overruns in government buildings and an association of architectural ornament with graft and corruption, according to historian Dan Bluestone. The City-County Building, meanwhile, came in just under its $2.8 million budget, constructed by supervising architect and Hornbostel protégé Edward B. Lee.

Hornbostel seemed to master a partial combination of elements that still left their constituent parts with some distinct identity—the office tower (albeit shortened here) and the municipal building, historic motifs and modern architecture.

It would be admirable to return, not so much to the historic styles of Hornbostel’s work, but to his ability to make rich combinations of divergent elements, which coexisted with such character.