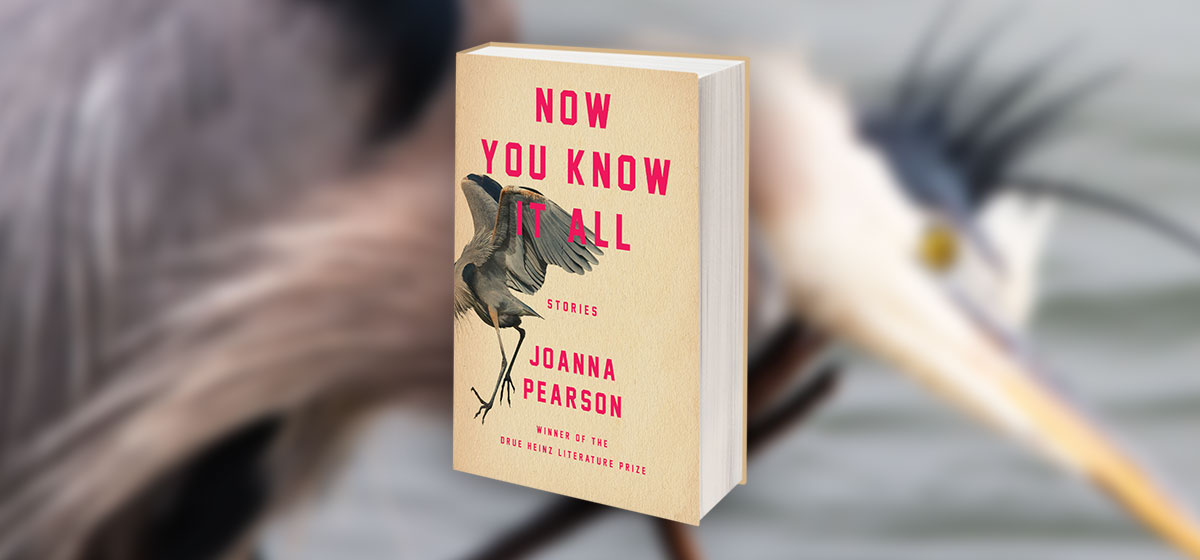

Characters Successfully Drive Drue Heinz Prize-Winning Work “Now You Know It All”

Fiction is full of self-deception. Perhaps what makes J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield and Vladimir Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert two of the most interesting narrators in contemporary literature is the way they continually delude themselves into believing whatever they’re selling. In a similar vein, author Joanna Pearson shows herself to be a deserving winner of the 2021 Drue Heinz Literature Prize for her compelling short story collection, Now You Know It All (University of Pittsburgh Press), which abounds with protagonists unwilling to face their situations until forced to do so.

In a recent interview with the Cincinnati Review, Pearson discusses her use of the unreliable narrator, saying that “Most narrators are, to varying degrees — and it’s a quality I love exploiting. Maybe reliable narrators exist, but only in this asymptotic way: you can get pretty close, but never all the way there. Even with a godlike omniscient third person, there’s still some perch or perspective from which the characters and actions are seen. There are just increasing degrees of subtlety or remove.” Using precise rendering of likable but flawed individuals allows conflicts to unfold on the page that will keep readers engaged in the lack of easy answers her conclusions withhold.

Pearson, a practicing psychiatrist based in North Carolina, goes on to say, “My day job involves a lot of thinking about how and why people are what they are, their motivations and desires, what they do, and the life events they’ve experienced. …The connections between this and writing are almost so obvious that I feel a need to declare very loudly: I don’t write about my patients, not even in a de-identified way! But in the indirect way that everything we live and do and encounter gets metabolized into our fiction, I’ve no doubt that my day job seeps into my writing. Real life is messy, though, whereas stories (I think) require a shape. I love that — it’s the fun part. In fiction every single moment bears weight and potential symbolism, every detail chosen for a reason.” In some of the strongest of the 11 stories, Pearson fashions real world events to be reimagined in interesting ways.

In “Darling,” the titular character has returned, years later, to her small southern hometown where she’d been recruited just before high school graduation by a Ghislaine Maxwell-type who grooms her to serve a Jeffery Epstein-like billionaire. This “ripped from the headlines” story works not because of its focus on the wealthy criminals, but instead because it allows a glimpse into the mindset of this fictional victim dealing with the fallout and tabloid headlines. In an ironic twist, Pearson has her hiding in plain sight at the same restaurant where she originally worked as a teen seeking a more glamorous life. “Darling was used to sloppiness. She was used to dirty napkins and sticky seats and loosely capped ketchup bottles, mushed French fries and smeared plates. She maneuvered through the restaurant detritus, avoiding crumpled napkins on the floor like a royal sidestepping dog droppings, and she’d perfected a way of looking down her nose when a patron, jokey and overfamiliar, said, ‘Darling. Now that’s not your real name, is it?’ Darling wouldn’t even answer, just cocked her head to one side, tapping her pen on her pad like it was an act of noblesse oblige even to be there…” When her high school boyfriend Clyde discovers she’s back in town, he tries to win her back, but regret keeps them grasping for straws and the story plays out like a delicious backwards Cinderella tale.

The fractured fairy tales continue in “Riding,” with Janet, driving through the desolate, somewhat-apocalyptic landscape of rural North Carolina during the pandemic, her sports car “the brilliant red of a fresh manicure,” getting rear-ended on her way to grandma’s house. The perpetrators, three young adults, offer her a lift, playing on the fears of it not being “a good time to be a woman sitting on the side of the road.” The story pivots to a flashback of Janet’s ex, Dan, who “found God” in a communal cult, and her reminiscing over the time they abandoned their broken RV to take up with a van full of heavy metal groupies. It becomes clear that Janet doesn’t know what she wants while her new friends don “horrifyingly convincing” wolf masks on their way to a psychedelic “full moon party.” It becomes clear that Janet is trying to break away from “the woodenness that shamed me” as again, Pearson keeps us guessing by turning tropes on their head in the first of what’s sure to be many stories coming out of the pandemic.

In “Dear Shadows,” Pearson uses the comeuppance of the #MeToo Movement to guide readers through the inner life of Katie, a thirtysomething editor for an alt-weekly in a college town who’s been following the career of her former crush Colin Reynolds, described as having “an air about him, even then, like he was on the verge of generating something monumental.” Creative writing classmates, their brief fling ended in 2000, a scene Katie characterizes as “one from a bad movie, but a bad movie you treasure and keep going back to watch, guiltily.” Now, Colin, mea culpa in hand, is a rising star in the indie-music scene with a career on the upswing, seeking Katie out in the same town where they attended school together after their encounter nearly two decades ago went sideways. After a phone call with Colin’s ex, Thea, Katie begins to view that night as something darker.

This story, like the others in this collection, works because the protagonists are relatable in their fears and experiences, but also well-rounded and rendered in ways that make them feel familiar. “She was forgettable, after all. Pleasantly so, like inoffensive background music in a shopping mall…Disarming…Homey. Her looks were like Fourth of July picnic food — who could find fault with that?” Likewise, there’s little to find fault within the 214 pages of Now You Know It All.