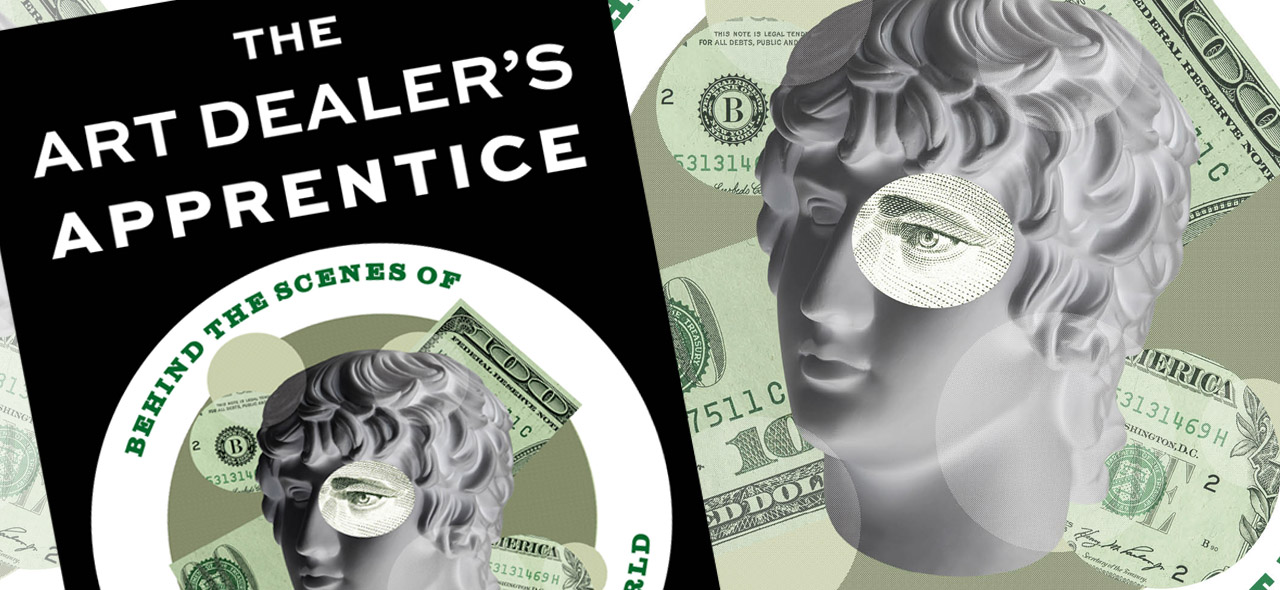

Buying Fragments of God: The Crazy Art World of the 1980s

If the 1960s changed America’s consciousness for the better, the 1980s certainly changed American commercialism for the worse. And to have lived during this latter period in New York City was to have felt the first tremors of this change, much like living near the epicenter of an earthquake and experiencing its initial shockwaves before the rest of the world takes notice.

David B. Guenther captures the zeitgeist of this transgressive era in his memoir, The Art Dealer’s Apprentice, partly to memorialize, and partly to apologize, for what happened to the art world at this time. Only a minor player — as a recent college graduate — he was, however, a key witness at the center of things, landing a job at a small, elite New York gallery, where he learned how to deal with the often outrageous, rarely sane players — the artists, collectors, dealers, and museums — who comprised this ecosystem, and changed it forever.

A highly episodic chronicle broken into 42 chapters, each with dozens of footnotes on the art he discusses, Guenther seems to be struggling with himself over whether he is telling the story of the artworld, his personal life, or that of his eccentric and fascinating boss, the respected gallery owner Carla Panicali, who hires him off the street and then comes to shape his life over the next three years of the book’s action — until the narrative ends just as the commercial art market crashes in the early 1990s.

The author is not an art snob, thankfully; he recounts the often-zany stories of million-dollar forgeries, thefts, fraud, smuggling, and mafia shenanigans with the bemused perspective of an outsider: a self-professed, simple Midwesterner, who just wants a good job to earn enough money to get a decent apartment and a new Brooks Brothers suit.

In fact, the most arresting parts of this story are those in which he describes the cultural ethos he is witnessing — like a traveler visiting a strange and exotic foreign land — without becoming subsumed by it. For example, his analysis of the famous auction at Christie’s, in which a Van Gogh painting was sold for the record price of $82.5 million — resulting in a standing ovation by the participants — is especially perceptive, as he states:

“[B]y acquiring The Portrait of Dr. Gachet, a buyer could acquire Van Gogh’s insight in the melancholy soul of Europe and make it his own. That was what people were applauding; it was only indirectly about the art. They were applauding, it seemed to me, a display of financial might, a new form of consumerism among people who believed they could appropriate to themselves an artist’s genius, who sought to collect and surround themselves with little visible slivers of the divine. Buying fragments of God could indeed become expensive.”

Guenther encounters the works of dozens of artists and devotes chapters to many of the most important ones his Panicali gallery deals with, including Kandinsky, Balthus, Dubuffet, Modigliani, Zurbarán, Rothko, Chagall, Renoir, Tamayo, Fontana, and others. He offers opinions on these painters and sculptors, some profound, some prosaic, but that is this book’s charm. It doesn’t try to be something other than what it is, unlike the art market of this period, which the author characterizes as spanning “the fakery, the genius, and everything in between.”

The strength of The Art Dealer’s Apprentice lies in its discussions of European Modernism — and especially niche movements such as Italian Futurism — which Guenther’s gallery specialized in. Very little is said about the more vibrant and certainly more fashionable “Downtown,” postmodernist scene transpiring concomitantly, engendered by artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Robert Longo. In fact, the author states that his boss, Carla, “would never deal in anything by Jeff Koons” — one of the paragons of this circle — and it “seemed odd that people would pay millions for what seemed like otherwise empty mockery.” But that’s what the aesthetic agon of the 1980s exemplified — with the old money faction happy to throw millions at art from the beginning of the 20th century, while the nouveau riche did so lavishly for works produced at the end of it. Such were the diametric ironies of this age.

Very little is recounted about Guenther’s personal life — only two brief chapters delve into this subject at all — or what it was like to live in the Manhattan of “the Big ’80s.” As someone who did live there commensurate with the timeframe of this history, I would have enjoyed reading this author’s impressions of the city’s creative landscape in general — as music, club, restaurant, literary, and fashion trends all coalesced with and infused the artistic environment.

However, there are many intriguing recollections of the nefarious figures that dominated the artworld back then — including some who were highly notorious, such as Andrew Crispo, the infamous dealer connected with (but never convicted for) the “Death Mask Murder” that was chronicled simultaneously in the hard-news and society pages at that time. The author dealt with him personally, and the details are compelling.

Aside from revealing the cloistered machinations of an eccentric and unique chapter in American history — as well as for providing an educational romp through 20th-century art history — perhaps the most valuable contributions this memoir offers are the irreverent, yet illuminating, insights regarding specific artists and works. Consider this appraisal of one of the most lionized European impressionist painters: “Renoir seemed almost unable to paint children’s faces; they often looked the same, like beach balls with stock features floating on their gauzy flesh-colored surfaces.” This encapsulates the often unctuous quality of Renoir’s work that hides in plain sight on museum walls around the world. Yet you would never hear an art scholar, let alone an MFA graduate, say something like this. But when you read this description it resonates with the power of something that needed to be said, but which most critics would not have the integrity to express in such a raw and unconventional manner.

Perhaps this kind of Midwestern frankness is what made the author so successful during the course of the tale he relates, navigating a milieu of ersatz cultural sophistication and hyperbolic artistic faddism, in one of the most ruthless commercial cities in the world. Even more so, it makes The Art Dealer’s Apprentice a stimulating and refreshing read.

The Art Dealer’s Apprentice: Behind the Scenes of the New York Art World by David Guenther will be published on March 5, 2024 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers for $36.00. Pre-order on Amazon here.