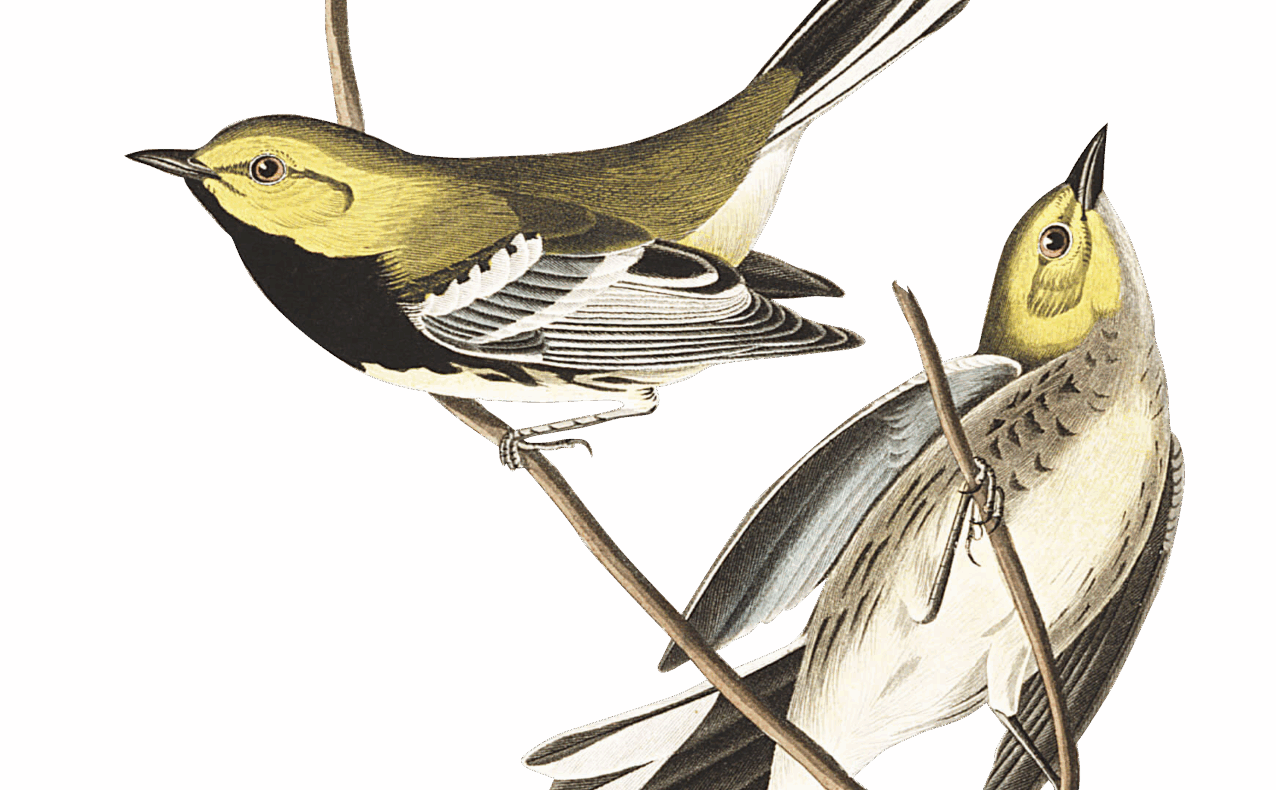

Black-Throated Green Warbler

The dinosaurs have returned! Birds are, by dint of evolution, a living link to dinosaurs. To remind ourselves of that, we need look no further than the Black-throated Green Warbler, a species that returned to western Pennsylvania in early April from as far south as Venezuela and Columbia and has been nesting and raising young for several weeks now, mostly north and east of Pittsburgh, where historically they preferred stands of Eastern Hemlock. Pairs tend one brood of three to five eggs, which are incubated just shy of a fortnight. Parents stuff nestlings with insects for just over a week plus before the hatchlings launch into the world.

Black-throated greens are small, canopy-dwelling birds whose song is often transcribed as “trees, trees, I love trees.” I’ve spotted them along the Upper Fields trail at the Audubon Society’s Beechwood Farms in Fox Chapel, but more often I hear their buzzy song. They are a lovely yellow and green on their heads and back. Their sides have black streaking with white wing bars, and the throat on males is indeed black. Females lack the black splotch and instead are white at the throat.

Their feathers are one compelling link to the dinosaurs of old. All birds have feathers, and any creature with feathers today is a bird. Back in the pre-asteroid era of T-rex and company, dinos had feathers, too. Modern feathers grow from tracts on the skin of a bird’s body. If you have ever cooked a chicken or turkey, you’ve seen the bumps on the skin where the feathers emerged.

Comprising keratin proteins, feathers allow for flight as well as providing waterproofing and insulation. (Recall your puffy coat now stored for winter and the geese and ducks sacrificed so we can stay warm. Besides the birds themselves, you also can thank outdoorsman Eddie Bauer, inventor of the down jacket, U.S. Patent D119,122;1940.)

Warbler feathers are not used for coat making, or any other utilitarian or decorative purposes, thanks to a treaty dating from 1918 protecting the lives and body parts of all migratory birds. Instead, the feathers of this insectivorous songster serve only to brighten up spring and summer months. They molt, or lose, their feathers and grow new ones in late winter, a phenomenon studied and codified by Philip Humphrey and Kenneth Parkes. Dr. Parkes was curator of birds at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History for many years, an international expert whose description of plumage molt in various species remains groundbreaking science.

Birds such as the Black-throated Green Warbler seem far removed from the creatures of Jurassic Park, but they remind us that science and beauty have long mixed in Pittsburgh. Whether you’re a casual bird watcher or a serious ornithologist, summer is the time to get outside and observe the natural world and all that awaits us there.