Sometimes winter brings surprises. Some are massive, like a burying storm; and some are almost unnoticed, like an unexpected bird on a branch. Now is the season to look for the Eastern Bluebird, whose flash of color can be as brilliant as a winter sky after a big snow or as delightful as an early sign of spring in the midst of clear, cold air.

We think of bluebirds as spring migrants, and many are, finding their way back to Pittsburgh after winter in the American South and Mexico. But bluebirds are omnivores, and though they eat a diet of insects and larva in the spring and early summer, tending growing babies with high-protein feasts, they can survive in western Pennsylvania on wild frozen fruits and berries in our frigid months.

I stumbled on my first overwintering pair of Eastern Bluebirds on a Christmas Bird Count about 10 years ago. Walking to the top of the Trillium Trail in Fox Chapel, I was drawn to the sound of running water. The day was cold, and my breath fogged the air as I climbed the steep hill. Dead leaves crunched underfoot, and tall, bare trees hung over the hillside. Reaching the top of the trail and the back of the Heinz estate, I scanned a pond for signs of avian life. I thought nothing was stirring until I settled myself long enough to hear the soundscape.

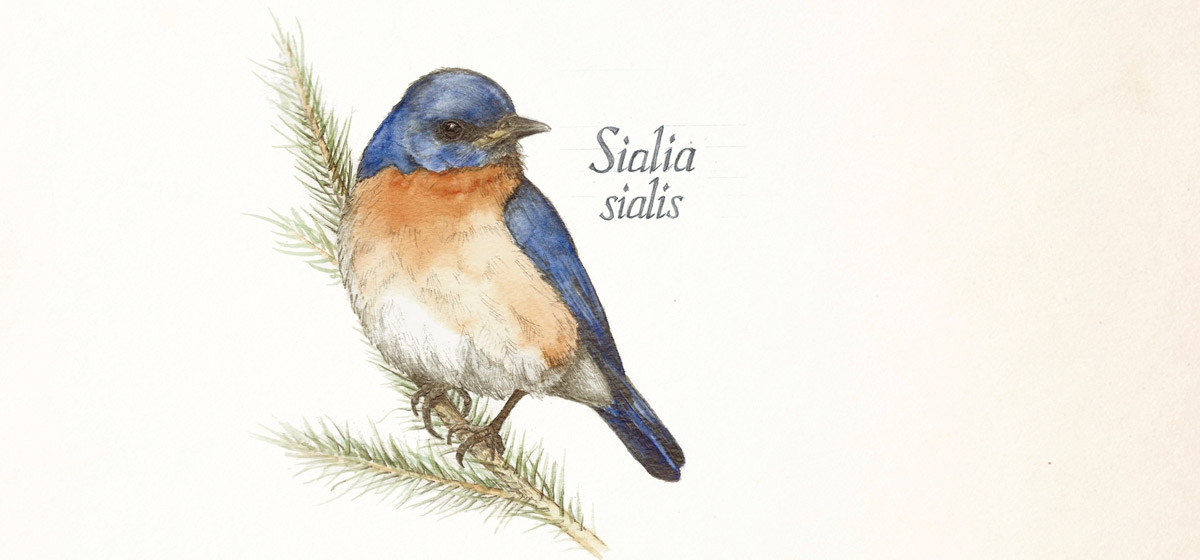

Then I noticed twitching and the faint sound of movement. I shifted my binoculars toward a small tree and saw a gray back, white belly and rusty breast. It was small and active, with an unremarkable beak. “What am I seeing?” I wondered. Then the male popped into view. In winter light, the blue didn’t flash at first, but then the bird hopped. The male’s primary blue back and rusty breast clicked. I was looking at a bluebird pair. They were gleaning frozen berries, working hard to stay warm.

Eastern Bluebirds aren’t here in huge numbers this time of year. The average Christmas Bird Count tallies 40–50, so bluebirds are a relative rarity. But now, after decades of decline, their numbers are stronger all year. Bluebirds thrived here in the 1800s and early 1900s, when Pittsburgh had wide open hillsides, hayfields, farms and orchards—all good for bluebirds.

The species is a cavity nester, preferring an old woodpecker hole or apple tree divot and fighting for prime real estate with other species such as invasive House Sparrows and our native chickadees, as well as open nesters such as robins and Blue Jays. In recent decades, bluebird boxes have helped bring the species back as well, especially boxes that exclude larger, more aggressive species like European Starlings. No doubt you’ve seen such boxes along our local highways, where bluebirds nest and use open fields as hunting grounds. (They won’t use a box on a tree in your yard unless you happen to live next to a field.) Bluebirds perch on wires above grassy fields or on fence posts, and I’ve seen small flocks of bluebirds atop the goal posts of football fields, the gridiron warriors of spring and summer, scanning the ground for hunting.

Male bluebirds identify potential nests in March and pair with females for a first brood in April, with a second and sometimes a third through summer. A typical nest has two to six blue-green eggs, incubated by the female for about two weeks. Once the naked chicks hatch, they fledge in about three weeks. Fully grown, they’ll have a nine- to 12-inch wingspan—about two-thirds the size of a robin—and weigh about an ounce.

Look for wintering bluebirds with the Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania on the Christmas Bird Count this year. Check www.aswp.org for details. Learn more about our local bluebirds and ways you can help them at the Blue-bird Society of Pennsylvania, www.thebsp.org.