Barebones’ “Lobby Hero” Combines Comedy with Tragedy to Stunning Effect

Dichotomies in art usually succeed brilliantly or fail dreadfully. Bringing together disparate forms is inherently risky: it challenges the artist, but even more so, it challenges the audience.

In the case of “Lobby Hero,” Kenneth Lonergan’s 2001 play about four people whose lives collide in a random apartment building lobby, barebones productions has dropped this Aeschylus-like moral tragedy into the format of a Howard Hawks-style screwball comedy, and the results are stunning.

Lonergan (an Oscar-winning screenwriter) is a master at evoking how people actually speak—when they are actually listening to each other. This is a rare talent and lets the nearly two-hour show transpire so smoothly that you’re actually disappointed when the intermission comes, as well as the ending. He foists no overwrought speeches or didactic proclamations which trip up so many contemporary dramatists. Thankfully, he lets the audience do the work it wants to do, without telling it what it should think.

But this can be for naught if the acting doesn’t meet the potential of the text. Director Melissa Martin has chosen a cast that is poignant and balanced. The four actors might have come from the set of a Mike Leigh film—as if they have been living their respective roles instead of just playing them.

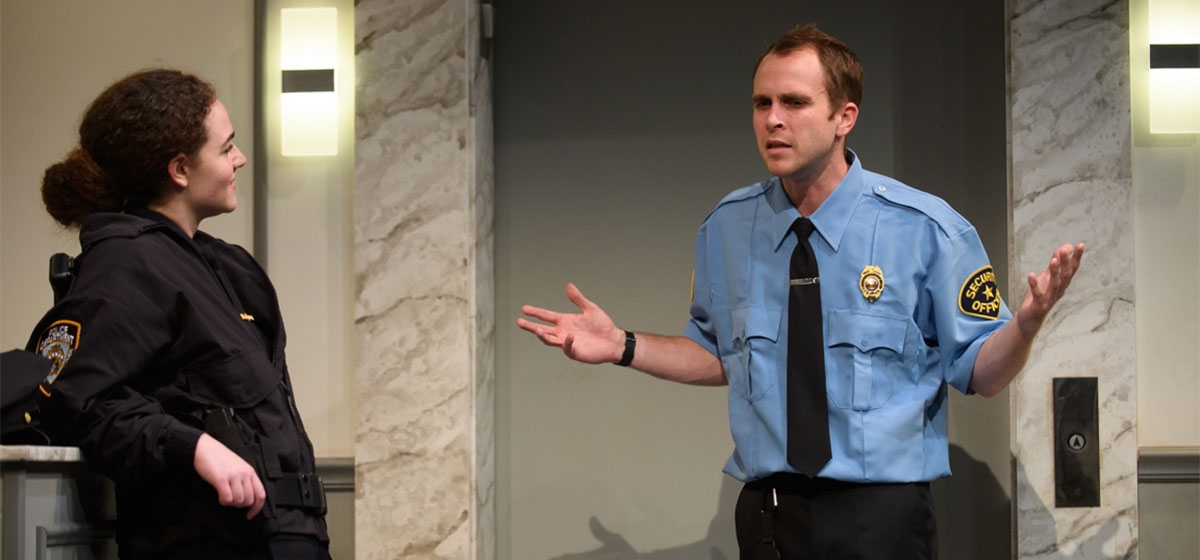

The characters they portray are the type of people you would never notice on the street—a security guard, his boss, a rookie female cop, and her veteran partner. And all of the action takes place in a non-descript, New York City apartment building lobby. It’s the kind of set we’re accustomed to for a mid-century, philosophical drama—like Sartre’s “No Exit”—where nothing is meant to distract us. In fact, it’s so monochromatic—a desaturated blue-grey—like a Nouvelle Vague film, that you almost expect the Criterion Collection logo to flash when the lights go down.

Technical director Douglas McDermott and lighting designer Andrew David Ostrowski have created this world with zen-like intensity. What they project is less “real” than it is “not fake.” The walls and doors don’t wobble. And the marble and steel elevator (all the buttons and lights really work) has a gravity much like the gravity of the elevator in “The Shining”—when it opens it functions as a kind of portal to something sinister. Nothing good goes up or down. And the room with its vapid, saturnine art (like the finger paintings of a child with no imagination) and hospital-tile floor, is a place of decay: it sucks the life out of everything that passes through it. Even the fake plants seem to be dying.

This is where we find Jeff (Gabriel King), asleep on the industrial divan, not even able to meet the minimal demand of consciousness his slacker job requires as a night-shift security guard. Jeff might as well be another fern in the lobby. He doesn’t even take pride in his loserness—you can tell by his unkempt uniform, which is two sizes too big. (It makes him look like a boy whose parents think he will still keep growing). He sums up his inferiority complex by stating, “My last girlfriend was a toll-both collector, and she intimidated the shit out of me.” Actually, his ex-girlfriend was really a prostitute, he reads cheap paperbacks, and he’s living in someone else’s apartment. So when a few interesting things start to transpire in his lobby, he becomes all ears and—to everyone’s consternation—mouth.

Jeff talks to people like a puppy humping the sofa. His only joy in life is getting any bit of attention he can, so he has become, by necessity, a genius at conversation. Playing this type of dynamic is a challenging task, but King does so brilliantly. (You may remember him from barebones’ “Small Engine Repair” three years ago, when he also brought great range to a quirky part). King may be the most comfortable person on stage since Groucho Marx. He uses his body like Jim Carrey uses his face—it can adapt to any situation. He is a master of postures, and will end up sitting, standing, or leaning on every object possible by the end of a performance. More important, his timing is voltaic. He makes even the most trivial dialogue fascinating by the way he listens, and instantly responds, to other actors.

In the tradition of Aeschylus, most of the scenes in “Lobby Hero” involve only two characters, and all of the violence occurs off-stage, so the focus is really on the dialogue. From the first scene between Jeff and his boss, security captain William (Rico Romalus Parker) the words are lived, not recited. It takes synergy between player and author to pull this off. And director Martin helps by keeping the blocking mostly organic (there are only a couple of instances where the actors commit “stage walk”—when it’s obvious they’re trying to hit proscribed marks).

William has a very sensitive switch that gets flipped quickly when he is upset by something he can’t control. He’s caught in a terrible moral dilemma (another Aeschylean trait) that has him on the edge of an existential crisis—his brother may have committed a murder and needs an alibi—and Jeff is just the man to trigger him one way, and then the other. Parker’s psychic reflexes in deciding when to pull this switch have to be brutally sharp; a lesser actor would make it look contrived, but he elicits pathos even in his most bullying, reactionary moments.

Director Martin has sped the delivery of Lonergan’s text, much as Howard Hawks sped the dialogue in films such as “His Girl Friday.” This is especially effective in the humorous scenes between Jeff and the other characters; the one in which he and Dawn (the female cop) speak over each other for an extended time is virtuosic, like hearing a sax and trumpet perform overlapping solos during a bebop jam.

However, just as the accelerated dialogue enhances the comic effect of the play, it mitigates some of the emotional impact as well. Speed has its price; like chemotherapy, it eliminates everything it touches, including all of the spaces, pauses, and breaks that might have been left alone, open, and silent. Employed constantly as it is by the director, it serves to dampen the resonance of many moments that might have had the chance to unfurl in the minds of the audience. Imagine listening to Bach in a church which has no echo.

A second dynamic arrives with the entrance of the two cops. Dawn (Jessie Wray Goodman) is a rookie still in her probationary period; she has everything to lose if she makes even the slightest mistake, yet earlier in the day she wacked a citizen over the head with her stick, sending him to the hospital. Bill (Patrick Jordan) is her partner, superior, and wants to be her lover. He’s been manipulating Dawn’s emotional vulnerability with the deceptive haze of romance; meanwhile he’s a frequent visitor to this lobby as he’s having another affair with a woman in the building. Of course, he’s married—this kind of guy always is.

Goodman’s performance as a young woman fighting to survive in the macho world of big city law enforcement is masterfully restrained. She eschews clichés in building her personae (one can imagine Hollywood putting a young Jennifer Lopez-type in the role: chewing gum, smoking, acting like a jock, etc.). Goodman has evolved tremendously as an actor over the past several seasons (even from her stint as Julia in Prime Stage’s “1984” only a year ago), and she’s now entered that rarified state where she’s willing to do whatever she has to for the sake of a performance, even if it means being so subtle that the audience may not catch it. Her New York accent—tight jawed and lurking in the back of the throat—is two subway stops short of Queens. (This is something barebones excels in: the nuanced way they handled the variegated strains of Boston-speak in “Small Engine Repair” went largely unnoticed by Pittsburgh critics).

Bill has the look of an outer-borough cop imagining he could be a Manhattan lothario if he can just get the mustache right. This guy is big, brash, and probably wears Old Spice because he thinks it drives the ladies crazy. At first Dawn falls for his donut-eating charm (we can only imagine the backstory of her daddy issues), but just when the plot starts to creep towards the conventional, Jeff the lonesome loser inserts himself into everyone’s business, and things fall apart, fabulously.

Jordan (who is also the company’s artistic director) is the kind of artist who likes to surround himself with other strong artists; this engenders a fearlessness which is contagious. No one is playing anything safe. And that makes for the most exciting form of theatre. You also get the sense—and the thrill—that no two shows will be the same.

The success of this and other barebones efforts partly stems from the nature of its intimate space—performances can be played more acutely, as they normally are for film, rather than broadly, as they usually are for the stage. Black box environments often mean cramped seating, poor lighting, and compromised productions, but here, instead, we find a sui generis atmosphere in which the cast and crew can fine-tune their work for discerning audiences like zealous audiophiles with the most sophisticated equipment.

In the second act, Lonergan’s strength as a writer of dialogue betrays him, because the action starts to get so wordy that it devolves from showing, to telling. A good rule for drama is that the action should be reducible to a verb (e.g. kill the king, steal the money, find the child). If the thing that needs to get done can only be explained, then it’s not really drama any more. It’s explication. (This is what makes plays such as “Hamlet” so sublime: as wordy as they may be, what fascinates us is trying to understand what was done and never explained). Thankfully, the excellence of the acting papers over these flaws in the script.

Jeff is manic and comical in his self-deprecation, but he’s not a clown, because he keeps the action moving forward, even if much of it is verbal. He grows from the doofus to the deus ex machina of the play, and becomes the source of resolution for each character, whether good or bad.

Ultimately, there is something unimpeachable about the quality of this show that makes the ending very fulfilling: a raw, Cassavetes-type of honesty is projected by these characters who may be lying to each other, but are not lying to themselves. “Lobby Hero” doesn’t end in comedy, or tragedy, but somewhere between these dichotomies—where past is not prologue for these souls, but the thing that makes the future a risk worth taking.

Barebones Black Box

1211 Braddock Ave

Braddock, PA 15104

barebonesproductions.com

888-718-42538