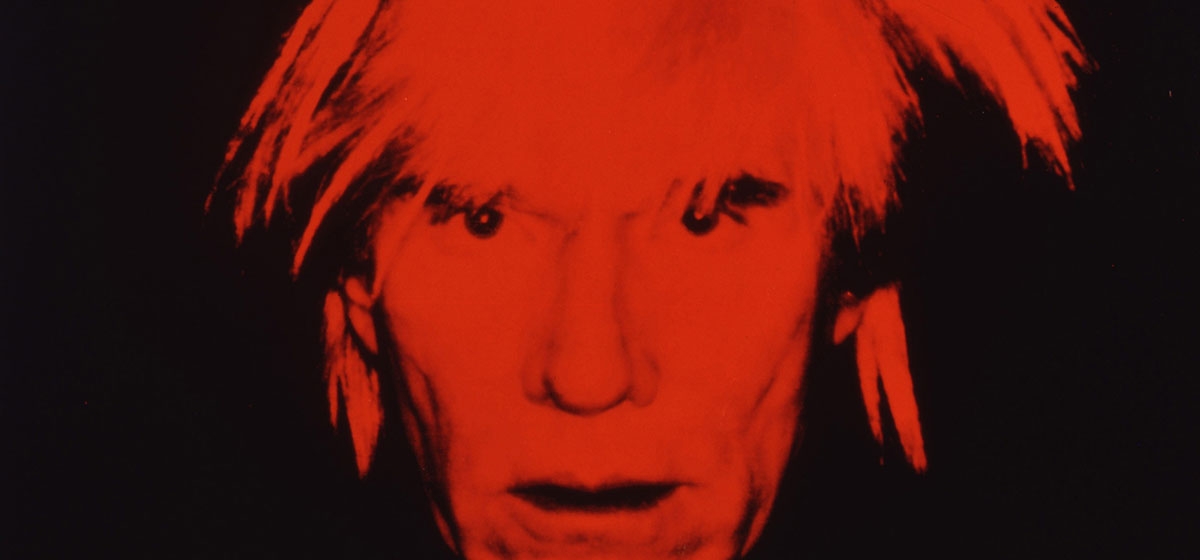

Sometimes when trying to assess the importance of any one artist, I am reduced to playing the auction trick. What’s it worth? People who have pooh-poohed Andy Warhol think twice when they hear one of his paintings sells for $14 million. It may be the wrong road to art appreciation, but in our glib, new world (partly created by Warhol) it may be the only thing that works.

And in this world, Warhol may be the most famous Pittsburgher of all time, more so than Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, Jonas Salk or even the city’s namesake, William Pitt, first Earl of Chatham. A Warhol show in Russia (supplied by the Warhol Museum here) can produce in excess of 500,000 visitors, twice that of the concurrent Carnegie International with its body of contemporary masters. Warhol can only have raised the profile of Pittsburgh, as visiting celebrities dutifully troop to his museum to be photographed. Stranger still, this dead, white man has become both icon to the young and status symbol for the older and richer. That’s a Good Thing.

But what effect has Warhol’s fame had on his alma mater, Carnegie Mellon University? There, among the art faculty and the student body an opposite view might exist, that Andy represents a Bad Thing; that his star shines too brightly, dimming the wider artistic achievements of a university highly rated, among other things, as an art school. The CMU school of fine arts has just celebrated its 100th birthday, presenting a convenient moment to gaze upon it.

Carnegie Mellon has no formal entrance to its campus, as was once planned. The vista of the site on Forbes Avenue at Morewood is coming to be seen as the normative “view” of the university, embracing as it does numerous elements of its varied architectural history. Earlier this year CMU alumnus Jonathan Borofsky installed one of his major sculptures, “Walking to the Sky,” at the entrance of this grassy mall. The work consists of a 100-foot stainless steel pole tilted obliquely towards the campus. Realistic human figures appear to defy gravity by walking up the pole to some imaginary destination. At the outset, the work gathered some criticism (all respectable universities practice spectacularly bitchy internal dialogue) but was hailed as clearly inspirational and optimistic.

Borofsky may not be a household name on the scale of Warhol, but he is internationally known and respected. An exhibition of his work opens Nov. 1 at the Carnegie Museum of Art. “Walking to the Sky” and related pieces have already been exhibited in 2004 in New York’s Rockefeller Plaza, last year in Dallas and in 1992 in Kassel, Germany.

The location of the sculpture is important. It was contemplated for installation elsewhere on the campus, but by placing the work on the perimeter, at a major entrance, it becomes a truly “public” work of art, engaging not only the university but also the city. Its context is accessible too, almost as blatant as communist posters promoting Mao’s dynamic China.

Conceptual art can trace part of its roots to the work of CMU alumnus (1962), Mel Bochner. In the autumn of 2004, Bochner and landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh created “an integrated work combining art and landscape design,” the “Kraus Campo,” located between the College of Fine Arts Building and the Tepper School of Business at the university.

This garden space is a medium for exploring ideas that have exercised Bochner over the years and is a response to concepts initiated or implanted in Bochner at the university. It is both permanent and organic. It is a public space, modeled after an Italian city square, as well as being like a private garden (a hortus conclusus) in which the mind can be refreshed. And the “Kraus Campo” is also multidisciplinary, another characteristic of CMU’s practice.

Both Bochner and Borofsky are senior alumni of CMU. Their work figures in the most recent Whitney Biennials and underpins the caliber of work that continues to come out of CMU and which is now physically present there. Less senior is John Currin, who graduated from the School of Art in 1984 but whose career has been, perhaps, the most meteoric of all. A group of his paintings was seen in Pittsburgh in the Carnegie International of 1999-2000. Most recently he has been in the news for switching galleries (the latest yardstick of fashionable chic), and ending up in Larry Gagosian’s gilt-edged stable. In 2004 his auction prices were in the region of $400,000. A year later they had doubled. No doubt they are now changing hands for $1 million. Currin, overturning expectations, masterfully handles the medium of painting, once declared dead by the avant-garde. “Thanksgiving,” 2003, is a work that is as ironically reminiscent of the 17th century as it is appropriate for the 21st — Old Europe and New America.

After a conservative beginning, the mid-1930s found a sense of modernism at CMU, with interest in hard-edged industrial imagery (as opposed to Gorson’s fuzzy, sentimentalized steelscapes) and a developing preoccupation with social issues. Samuel Rosenberg, teacher par excellence, was sensitive to these sea-changes. By the 1950s, he washed up, a little uncomfortably, on the shores of abstraction, along with his contemporary Robert Lepper. More importantly, these artists created the climate that permitted the emergence of CMU’s first nationally significant wave of artists, most notably Phillip Pearlstein, Andy Warhol and Joyce Kozloff, who graduated in 1952.

The last few decades have seen extraordinary changes at the university, propelling it in rank past many Ivy League schools. The school of art has benefited from and contributed to this change. Essentially the faculty has adopted a more collaborative approach than many other universities. Groups within the university, such as leries seem to be endlessly exhibiting work from this Pittsburgh source. More than 50 universities worldwide have formalized links with CMU.

Despite their best endeavors, though, universities tend to be seen as closed societies, often by their most immediate neighbors. Despite being generally open, university galleries are seldom visited by the public, a loss to both.

CMU’s Regina Gouger Miller Gallery, for example, is a handsome space with an excellent exhibition schedule. We need to know more about these university galleries.

When Don Celendar, a professor of art at CMU and a noted conceptual artist, died last year, his obituaries reported that he had once asked the H.J. Heinz Company to fill the Grand Canyon with tomato ketchup. It was a noble concept and one that would have united town and gown for all time in a magnificent gesture.