An Uncommon Life in an Ordinary Place

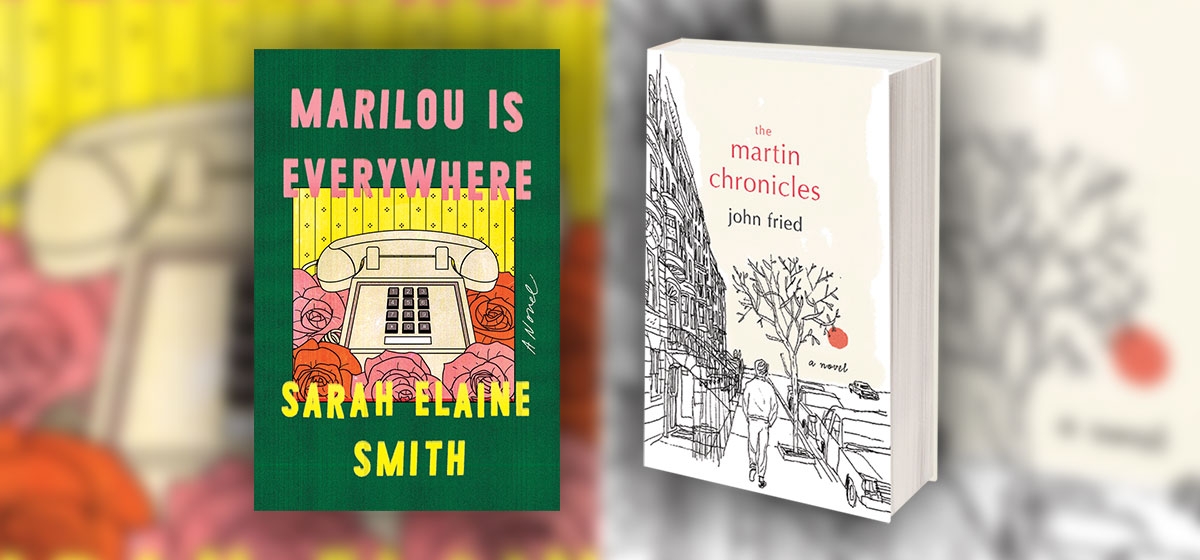

It would be a shame if this strange and glorious book set in Greene County becomes pigeonholed as “a voice from the heartland” or “a rare glimpse inside the Other America.” Sarah Elaine Smith, a Greene County native now living in Pittsburgh, has surely drawn on observed experience for her first novel. But the Carnegie Mellon University creative writing graduate with an MFA from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop has thrown down a tale that transcends place. The dexterity of her writing and the intricacy of the story make “Marilou Is Everywhere” deserving of another familiar tag in the book world: a stunning literary debut.

“I was 14 and ruled by a dark planet,” declares Cindy Stoat, by way of introduction. She and her older brothers, Virgil and Clinton, “had turned basically feral since our mother had gone off for a number of months and we were living free, according to our own ideas and customs.”

There’s a shade of Huckleberry Finn here, who was about that age as he set off on his adventures. But Cindy, who doesn’t wander from Greene County, craves the stability of a home and a present parent. Her father was never on the scene.

She falls into that opportunity when a slightly older girl from the area, Jude Vanderjohn, goes missing. The girl’s mother, Bernadette—an eccentric ex-hippie who is flush with money from fracking leases—is bereft, delusional and prone to overdrinking. Virgil, a handyman who cuts Bernadette’s grass, arranges for Cindy to live largely with Bernadette, who is comforted with the delusion that Cindy is Jude.

Cindy’s mother, Donna, does show up from time to time. But home life is one of electricity shut-offs, scrounged meals and menacing advances from brother Clinton. Bernadette, meanwhile, came to the region years ago from points unknown with books and curious vegetables and posters from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “At home, we were always watching a courtroom TV show about roommates who couldn’t agree on whose turn it was to pay for cable,” says Cindy. “At Bernadette’s, I ate pomegranates and read Khalil Gibran. … So much of her custom was strange to me. We ate dinner by candlelight when the electric worked perfectly fine and the bill was all paid.”

Virgil and Jude had been a couple for some time during high school. “As a private joke, they called each other Marilou and Cletus, and would discourse in the halls like high-toned rustic gentry.” As an homage, Virgil wrote “Marilou Is Everywhere” in glow-in-the-dark paint on the wall of the school choir room, which explains the title on one level. As Cindy gets deeper into her appropriation of the life of the missing Jude, another meaning becomes evident.

Inevitably, Virgil comes under suspicion for Jude’s disappearance and ends up, unjustly, in jail. But when Cindy comes across a clue to the mystery, she becomes delusional herself, seeking to prolong the world she has created.

To say more about the story would spoil its satisfying denouement. But it should be clarified that, based on the public record, “Marilou Is Everywhere” is not autobiographical, at least from the Cindy side. “My parents were lefties with homemade bread and Midwestern accents,” Smith wrote in an essay published on her website. “I didn’t really know how to be from where I was from.”

More revealing is another line from that essay, which is about a photography project that she and a friend embarked upon in high school. “There isn’t a lot to do in Greene County,” she said, “but there’s a lot to see.” Imaginations can be fired in every corner of this world.

Adolescence revisited with all its awkwardness

John fried, a Duquesne University professor of creative writing, has written the very model of a modern coming-of-age novel. He details the searing and soaring emotions of adolescence and its aftermath in a calm, methodical and enchanting fashion. As the chronicle of a white middle-class boy, from age 11 to 17, the story might connect more directly with those of us in that unoppressed demographic. But I contend that “The Martin Chronicles” has universal appeal to anyone who enjoys a good yarn, and who wants to revisit the travails of youth from the relative comfort of middle-aged wisdom.

Martin Kelso lives on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and attends a private school that requires uniforms. He’s an only child. His parents are well-adjusted. Dad’s a lawyer and we don’t learn much about his mother, other than that she can speak Spanish with the Dominican men who operate the elevator in their West End Avenue apartment building. It’s the 1980s—an era when a family did not need a gargantuan income to live in Manhattan. Martin’s life is neither elite nor uncomfortable. To him, New York “was this giant city but sometimes you felt like it was a small town and everyone you knew lived within arm’s reach.” But he knows his place in the world. His school goes on alert because of an uptick in muggings. “Principal Conrad announced at assembly that several kids from Welton, a super rich private school across town, had been mugged walking home. … I didn’t think much of it. Welton was on the East Side, a world away from where I lived. They might as well have been mugged on the moon.”

“The Martin Chronicles” is modern in its construction. The 10 chapters are structured as freestanding stories. You could absorb it all in one sitting, like a binge-watch, or read each story like an episode in a Netflix series. The writing, however, is timeless. Fried, a former magazine editor and writer who has taught at Duquesne since 2004, makes his style invisible—no gimmicks, just enveloping prose in service of the story, with humor that arrives organically.

Martin (and here is where your reviewer identifies) is flustered by girls. In sixth grade, he shows his affection for Alice Jakantowicz by 1) labeling her “Brace Face” because she has to wear a big wire retainer around her mouth in school and 2) stealing the retainer when she removed it to eat lunch. At home, Martin’s cousin Evie, four years older and practically a sister, spies him in his room trying on the retainer, and showing the effects of imagining being physically close to Alice. (“Gross!” she exclaims.) The next day in school, there’s a quiz to demonstrate knowledge of homonyms. Alice writes on the blackboard: “I know Martin stole my retainer. He can’t say no.” The class erupts in pandemonium. “I walked back to my chair, my mind racing,” Martin thinks. “I couldn’t figure out how she knew. Had she seen me put it in my bag? Why didn’t she stop me? Had Evie told her? How could she know Evie? Did all girls know each other?”

Each chapter/story is like a growth spurt. Martin’s life becomes more complex. His guy friends get real girlfriends. He becomes entwined with class struggles, from replacing the striking elevator operators in his building to turning into a plaything for one of those truly privileged Upper East Side girls. The specter of death looms throughout, and catapults him into maturity by the end.

The character of Martin Kelso does not cry out for help. He is a decent, befuddled every-guy, an observer of the world. He’s not weary like Holden Caulfield (another New York private-school type) or decadent, as we imagine Manhattan-bred kids to be. When his friends start having more complicated birthday outings—Broadway shows, fancy dinners—Martin sticks with a bowling party, fueled by pizza and ice cream cake. His resolute ordinariness provides a big canvas that all readers can paint themselves into.

Yet as he sums up his life at the end, “I was (and still am) haunted by moments when the world seems to press down on me from all sides as if I am underwater.” If that doesn’t ring true, you’re not normal. “The Martin Chronicles” makes you glad that when you were a kid, you didn’t know then what you know now. What fun is being grown up without having endured angst?