Damon Young recently bought a rather nice house a block away from me. Yet I don’t expect to be invited over, although I am about to lavish praise on his brave, incisive and witty memoir about growing up and living while black in Pittsburgh. Even a blurb-ready assessment—Damon Young is not only the city’s most engaging writer, of any melanin level, but he is also an essential American voice—won’t do the trick. I know this because he says so, right in the middle of the (brilliant) essay “Thursday-Night Hoops,” about the pickup basketball game he adores playing at the Central Catholic gym every Thursday with a bunch of white guys.

The fellas share beers after each game. Most socialize together, too. Young has attended Memorial Day barbecues at one guy’s home, but he’s never invited a fellow hoopster “to spend time with me and my people.” He tells himself it’s “for their own good.” They wouldn’t enjoy attending a gathering “where the jokes and conversations occasionally veer into some variant of ‘funny and/or [messed up stuff] white people do.’ ” The bottom line, however, is that “I just don’t want them in my house. I haven’t been possessed with the inclination to grant them that privilege, and I wouldn’t want my friends or my family or my wife to feel the need to redact themselves in one of the few spaces we’re able to freely regard white people with callousness and mundane and hilarious cruelty.” Young concludes that “[t]hese are not bad guys. But they are white, and whiteness already takes up too much space for me to volunteer my own.”

If you are reading about the work of Damon Young for the first time, and are white, and are perplexed by that passage, please don’t holler for the double-standard police. Hold my lily-white hand for a moment and take a breath. Let me make the case that Young is not a “reverse racist,” or rendered irrational with “black rage.” He is, at age 40, the American writer who could bridge our racial divide and bring about deeper mutual understanding and harmony. What’s his magic touch? It’s simple: Young doesn’t appear to give a darn about healing America’s racial wounds. He writes as if that’s the furthest thing from his mind, a lost cause, a chimera wrapped inside an enigma.

Damon Young writes to tell the truth of This Black American Life, in painstaking personal detail and with laser-like acuity. The majority of those truths are told in side-splitting jest, sometimes as profanely magnificent as a Richard Pryor routine, but just as often droll in the vein of David Sedaris. Young writes less from anger than from two other A-words—anxiety and awkwardness, the two conditions that nurture his empathetic humor of recognition.

Young co-founded a blog called “Very Smart Brothas” in 2008. He had been laid off from a decent-paying job at Duquesne University’s Career Literacy for African American Youth program, a casualty of the recession. Poetic justice prevails, because he and his partners turned VSB into a career, flooding the zone with highly literate posts about black America, for black Americans. VSB “emerged as a stream-of-consciousness sounding board, an expletive-laden fuse and an absurdist inside joke,” as The Washington Post put it. Last year, a major online media group bought Very Smart Brothas and the work carries on with the same verve.

I have been marveling over Young’s snappy online writing for years (thanks to social media delivery, not because I bookmarked VSB. Hey, I’m a white guy). It is deeply satisfying to hold a printed book in my hands and dive into his polished essays, which show a mastery of the form while retaining the crackle and pop of his VSB missives. Providing evidence in a review is difficult, because you need a full page from the book to appreciate the cadence, and we’d have to bleep out profanities that are as essential here as they are in “The Sopranos.”

Speaking of words that won’t be printed here: Young uses, when clinically necessary, the term that we all agree to call “the n-word.” He uses, constantly, the variant that ends in the letter “a,” the neutered appropriation of the vile slur. And in the book’s tour de force essay, “Three [That Appropriated Word Ending in ‘A’],” he provides a full-bodied explanation, from a real-life situation, as to why even the coolest white folk can’t get away with deploying the term: “It’s one of the few privileges unique to blackness that remains sacrosanct, untouchable, and unco-optable.”

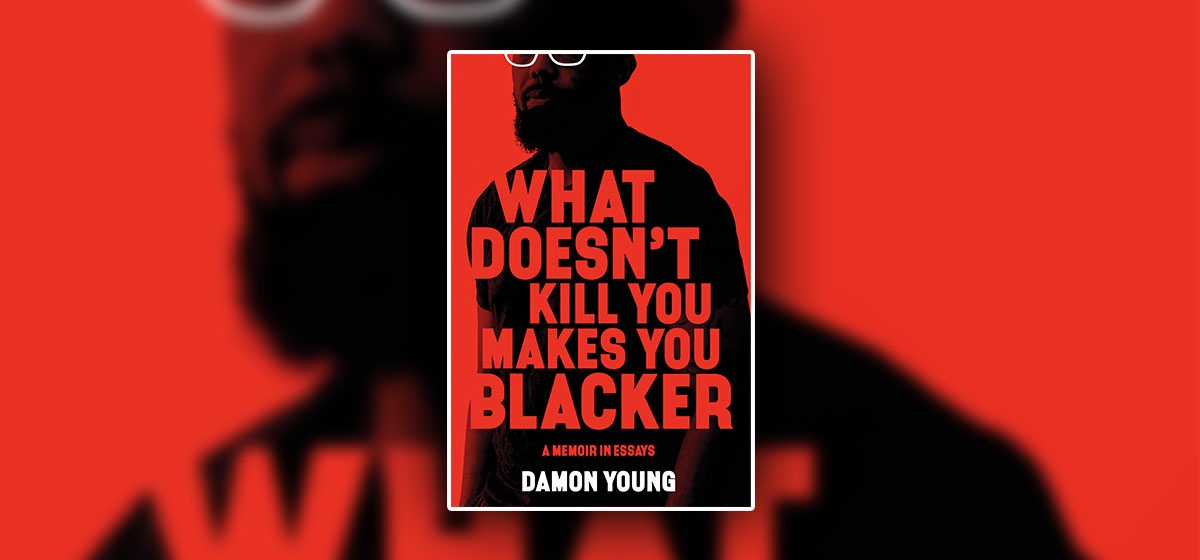

That essay stands out because it’s the one piece that gets overtly argumentative. The pleasure of “What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker” is following the arc of Young’s life and watching it come together like a quilt as the essays stitch together. It’s a Pittsburgh story through and through, from his childhood between a tough block in East Liberty and a more pleasant Penn Hills, raised by parents with sometimes precarious finances but no shortage of love and attention. His basketball prowess got him a scholarship to Canisius College in Buffalo to earn a degree in English, and post-college days find him teaching in Wilkinsburg, running a youth program in McKeesport and watching a plum job at CMU evaporate because he did not, at age 25, have a driver’s license and the position required travel. His girlfriends are brainy high-achievers; he hangs with a crew of women who call themselves the “PhDeez.” A whole essay is devoted to his wife, Alecia, a perfect match, and their young daughter, Zoe, 3, for whom Young has the greatest hopes, and fears (and the next edition can include an essay about his son, Levi, born in December).

The teaching job in Wilkinsburg prompted the book’s most nimble essay. It also contains a passage that is the most striking illustration of the segregated lives we lead in America, and Pittsburgh specifically. Titled “No Homo,” the piece describes the conflicted alarm he felt when the students began to whisper that he was gay. A proud progressive, Young is no homophobe. He’s an athlete, but reserved, not outwardly macho. What got people talking, however, was his wardrobe—Dolce & Gabbana belts, Versace crew necks, Armani Exchange jeans, upscale duds that were not common for men in his circles. “I’d use clothes to shield me from whatever anxieties I possessed,” he explains. But what struck me was the provenance of the threads: Shadyside’s Walnut Street—a place that he didn’t know existed until he graduated from college: “This block sat a mile and a half from the block I grew up on, yet my universe then was such a stark contrast from the universe Walnut existed on that it might as well have been [expletive] Neptune.”

“What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker” may not be the feel-good book of the season, but it may be the most “felt” book I’ve read in a while. Will it be a crossover hit? Only if white folks make the step.