An American Lawyer in China

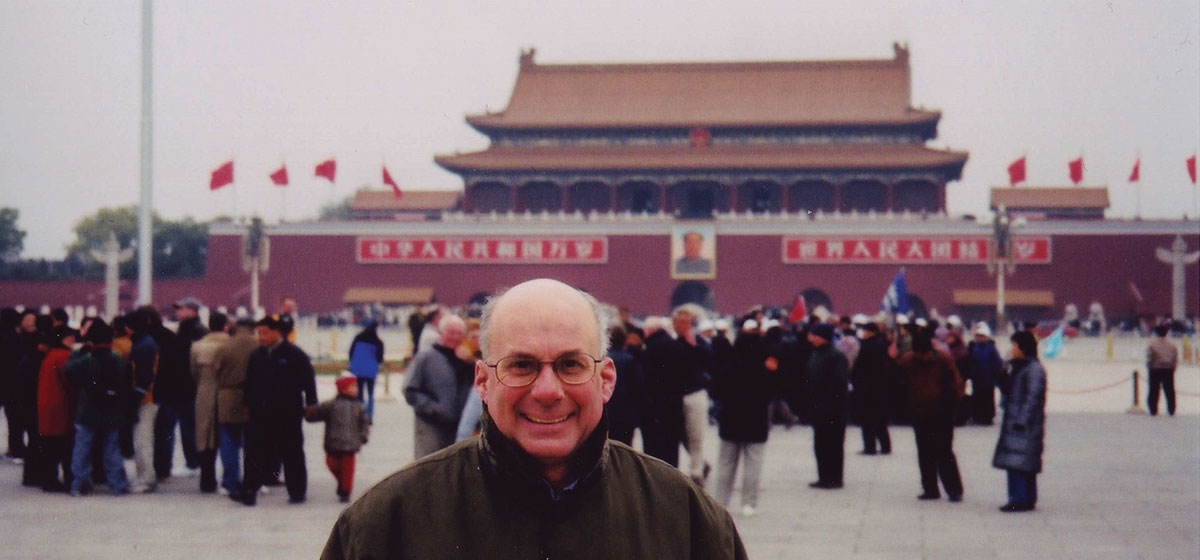

Twenty years ago I visited China for the first time, and my view of the world changed forever. This took me by surprise. I had studied China at the University of Virginia as part of a lifelong fascination with the country and its people, and I mistakenly thought I “understood” China.

I came to realize that it is a very long way from Pittsburgh to Beijing in more ways than one.

Over dozens of trips since then, I have learned that there is really no one definable China. My favorite Chinese saying is “We are in the mountains and the Emperor is far away.” This reflects a simple reality that the more removed one is from China’s central government, the more diverse things become. Beijing is a typical political city with overwrought buildings in the Mao/Stalinist 1950s style exuding an atmosphere of control. A mere 90-minute flight away is Shanghai, perhaps the fastest-growing city in the world. The people there are confident, aggressively commercial, and literally a world away from the government capital of Beijing. To the south lies the Pearl River Delta, which stretches from Guangzhou (Old Canton) to Shenzhen to Hong Kong. Since the early 1980s, this region of 42 million people has exploded into the manufacturing heart of China. Much of what was once produced in America’s Midwest now comes out of thousands of factories populating the Pearl River Delta. Standing alone, it is the 16th largest economy in the world. They even speak a different language (Cantonese), and their attitude toward life and business is unlike anywhere else in China. If you travel west to Kunming (which is north of Vietnam), you encounter a China with a distinctly Southeast Asian flavor. These vast regional and cultural differences made me realize that in order to interact and successfully do business in China, I had to constantly adapt to diverse local needs and customs. This is a never-ending challenge. After 20 years, I still learn something new on every trip.

During every visit to China, its raw energy slaps me in the face. It reminds me of my grandfather who came to America as an impoverished immigrant from Yugoslavia in the early 20th century. As a child, I remember looking through his scrapbook of old black-and-white photographs of Pittsburgh that graphically portrayed the smoke, soot and heavy pollution that accompanied the city’s steel production. The biographer James Parton once described Pittsburgh as “Hell with the lid taken off.” Chinese cities of today, like Wuhan or Harbin, closely resemble those old photos of Pittsburgh 50 to 80 years ago. I quickly discovered that most of China is not postcard-beautiful — it is chaotic and the pollution is shocking. But underneath China’s drive to grow reflects a fierce vitality and challenge to those who want to compete within the Chinese economy. Halfway attempts are doomed to fail — China demands your best efforts.

Another lesson I have learned is that nowhere in the world is “face” more important than in China. Again and again over the years, I have seen the consequences of thoughtless actions by Americans, inadvertent or not, resulting in embarrassment to someone and thus causing loss of face. An intuitive understanding of the concept of face is why the Chinese are among the best negotiators in the world. Face is universal, but understanding how the Chinese use it to their advantage forces everyone else to step up and do the same.

Perhaps my most personal lesson in China was the most unexpected. Western Pennsylvania is a geographic region with a relatively small minority population. Unlike the 19th and early 20th centuries, there has been limited immigration here over the last 40 years. On my first trip to China, I remember walking down a busy street and feeling lost in a sea of humanity. It was the first time in my life when I looked around and realized that I was the only white face anywhere. It struck me then, and I have never forgotten, what it means to feel like a minority. This has sensitized me to what it must be like to live in a society where people are always looking at you as an outsider.

My business travels to China over the years have opened my eyes in so many ways, and now I look at my two university-aged children who are just beginning to contemplate their professional lives. The challenge facing them and the rest of their generation is stark. The U.S. today counts for 6% of the world’s population, yet it controls over 40% of the world’s wealth. Everyone outside of America wants what we have and are finding new ways to get it. Only through hard work and the better education of our children will America be able to meet this future competition and maintain our standard of living in the coming years. China, for example, graduates nine times as many engineers each year as the U.S. In this vastly competitive arena, it is the growing economies like China and India that pose the greatest challenge to America’s prosperity. We need to look at how the world really is if we want the next generations to do as well as we have.