A Template for a Life of Learning and Art

I am a sucker for process. my favorite part of the Andy Warhol Museum has always been the top floor, where Warhol’s wispy childhood sketches hint at his expert ability to replicate reality and also his interest in amplifying his favorite parts of it. When I look at those early pieces, I am reminded that all labors, like life, proceed in stages.

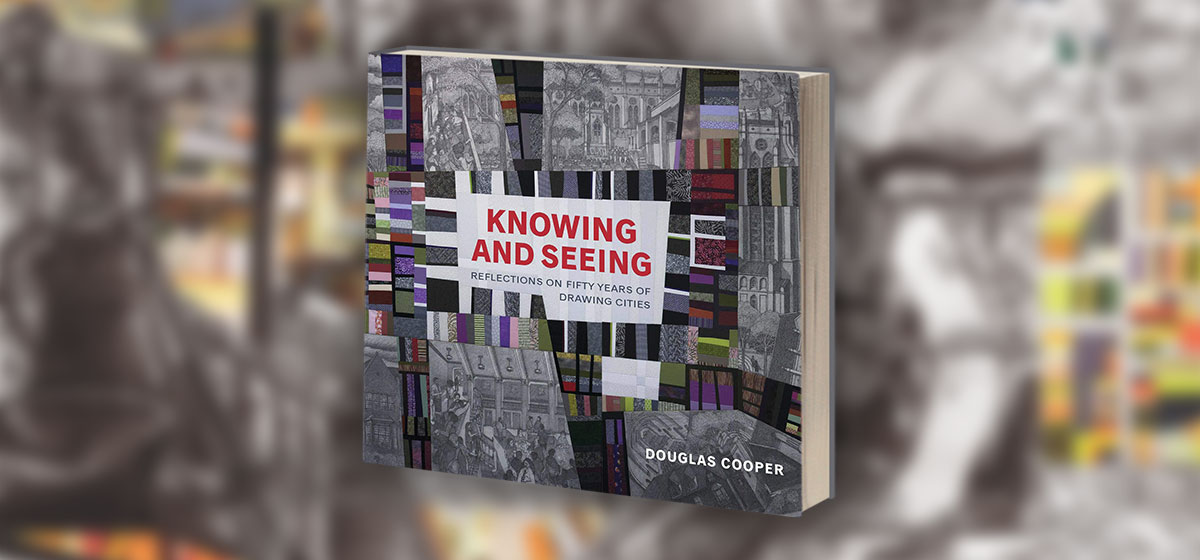

So it’s no surprise that I adore Douglas Cooper’s mesmerizing new book, which catalogs every stage of his career and also every laborious stage of his most famous works. It’s as though a seven-floor Cooper museum has been artfully crammed into one big gorgeous book. Most Pittsburghers have likely come across his charcoal panoramic murals of places such as Polish Hill and Woods Run. If not, some of Cooper’s best work is on display at the Senator John Heinz History Center and at Carnegie Mellon University, where Cooper teaches hand drawing in the School of Architecture.

But only in Knowing and Seeing: Reflections on Fifty Years of Drawing Cities can a Pittsburgher see drafts from the “collection of the artist.” In his sketches, you can see Cooper begin to twist a landscape ever so slightly. Then, in dozens if not hundreds of beautifully printed finished products, you can see Cooper fully realize those twisty initial hunches. The University of Pittsburgh Press has arranged the book so that several selections can be pulled out to better appreciate their panoramic brilliance.

Yet Knowing and Seeing is much more than a visual retrospective of Cooper’s career. Cooper is a gifted writer, and he has woven a terrific, reflective memoir throughout the book. Whereas an emerging artist is often unable (or unwilling) to reduce his artistic approach to a simple description, Cooper is a humble, insightful critic of his own work. He describes his style better than I can: “My drawings have tended to have a common underlying compositional structure: a placid horizontal at the top, a wiggly U following the rivers and edges of intermediate shelves, and paths that follow the hollows and connects foreground and middle ground to background.”

Cooper regularly cites topography, and not by accident. Rather than impose a specific method on top of Pittsburgh’s landscape, Cooper derives his distinctly circuitous style from the ground up. He describes how the city “invited me to look up at the undersides of porches, down steps,” to appreciate and capture how the city’s “plateau tops and mid-slope overlooks offer easy visual connections to other locations in the city.”

Art, Cooper seems to say, is just an avenue for looking closely at what’s around you.

Cooper is able to examine more than just Pittsburgh. In Knowing and Seeing, he takes a hard look at himself. Midway through, he recounts a moment in 1989 when he was invited to present a retrospective of his drawings at the American Institute of Architects National Headquarters Gallery in Washington, D.C. The event was “a real coup for me,” he writes, yet he recalls his misgivings about his work at the time. Though his pieces were “technical marvels, they seemed lifeless to me.”

Suspicion regarding one’s success is something of a hallmark for major Pittsburgh artists. Cooper’s expression of doubt in the middle of his career reminded me of John Edgar Wideman, the Pittsburgh-born novelist who felt a similar unease about his standing as a mid-career writer. “By 1973,” Wideman writes in the introduction to “The Homewood Trilogy,” “I’d published three critically acclaimed novels. It was hard to admit to myself that I’d just begun learning how to write.”

Wideman kick-started the back half of his career by returning to his Pittsburgh roots. For Cooper, it would seem that the fundamental shift occurred when he more fully embraced collaborative pursuits. In Knowing and Seeing, he recalls how he worked alongside senior citizens at a social center to artistically recreate Pittsburgh locations that no longer existed. His wife and School of Architecture colleague, Stefani Danes, has been an instrumental co-creator in projects such as the recently installed “The Collaborative Campus” mural at CMU’s Tepper School of Business. In the same way that topography has served not merely as a circumstance but an influence for Cooper, collaboration, Cooper writes, has become “more than just a response to practical necessities. It has had a profound impact on the

character and content of the work itself.”

It’s reflections such as these that make Knowing and Seeing so much more than simply a beautiful coffee table object (though it’s a knockout in this category). Cooper provides a template for how to commit oneself to a process, detailing what he has read, where he has traveled, and what has influenced him. It is extremely telling that the book’s foreword and afterword are written by two of Cooper’s mentors. The book frames Cooper not as an artist or genius but as a student first and foremost.

Students of all ages and disciplines would do well to follow the template for growth that Cooper has laid out in Knowing and Seeing. Find good mentors, Cooper’s book advises, then listen to them. Assemble worthy influences, then study where they align, diverge, and sneak up on each other. Let your surroundings inform your style, then question this style. Collaborate, and don’t stop.