A Life Caring for Fallingwater

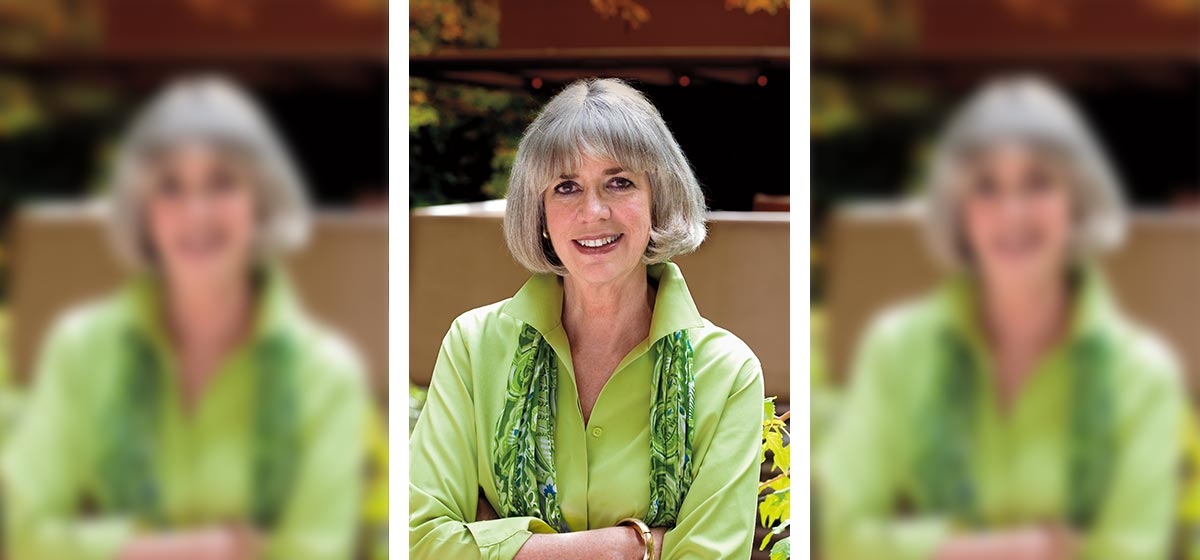

Lynda S. Waggoner is vice president of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and director of Fallingwater. On the occasion of her retirement, we asked her to look back on more than 50 years at Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece.

Q. How did you get involved with Fallingwater?

A. I was a senior in high school in 1965, and my mother was a friend of Mrs. Hagan who owned Kentuck Knob. She heard they needed guides at Fallingwater and said, “Lynda should apply.” So I did. I remember vividly coming down the path, rounding the bend and seeing the house for the first time. And I knew at that moment my life had changed. I grew up in Farmington, Pa.—not exactly the cultural center of the universe. I hadn’t travelled widely and lived a very sheltered life. I saw the place and realized, “This is going to change my life.”

You’re so impressionable at that age. The senior guides for the most part had teaching positions in Pittsburgh. Some had been in Pitt’s art history department, some were from Chatham, and some were CMU architecture students. Being a young kid from a rural part of the world, being in conversations and getting to know these people was a wonderful experience. I worked there summers and weekends during high school and then through college. I returned in 1985 as a curatorial consultant and in ‘86 was made curator and administrator of the site. I’ve been the director since 1996.

Q. How has Fallingwater changed?

A. It wasn’t nearly as busy in the early years. There was no visitor’s center—that was in the gardener’s cottage. There would be hours in the day when no one was coming, and as guides we had incredible freedom; we would take books off the shelf and spend hours reading. Today we might have 1,000 people a day—there’s no down time. There’s a visitors center, a museum store and a gallery on the site. The house is also in better condition than it was then. Edgar Kaufmann Jr. donated the house to the Conservancy late in ’63. It didn’t open to the public until ’64. In the early days, he wanted to see how the Conservancy would do managing the site. The arrangement was that he would maintain ownership of the collection in the house—the art and the objects—you didn’t know what was going to come or go. I can see him walking down the path with something in his arms to give to us.

One of the challenges when I came back was that the wood furnishings were in horrible condition. The house had many leaks, so there was water damage, but also UV light ray damage—there aren’t blinds or curtains. So my first challenge was to get a handle on the woodwork—we were losing it. A few pieces were irreparable. I consulted professional wood conservators, but the cost was more than we could afford. Tom Schmidt, our first real director, went to Edgar and worked for the donation of the collection—so that we could manage it and public grants could support its care. Tom was a wonderful person to work for. He has a great heart for Fallingwater.

Q. How did tourism to the site it grow?

A. It kind of grew organically over time. By the late ’70s visitation was 70,000 and Tom oversaw the building of a visitors pavilion. We really focused on the visitor experience.

Then we started tackling issues of the building. There were 50 some leaks when I arrived. We got it down to maybe 10, and we’re still working on that. It’s a flat-roofed house in a Northern climate and cantilevered over a stream. There were issues with the concrete and paint. We brought in a lot of experts and were feeling really good about the building in the mid ’90s—until a University of Virginia engineering student called me. He had done a paper using computer modeling on how the structural systems and cantilevers worked. He said, “I have to tell you, I cannot explain why the building is still standing. The building should have collapsed.”

I told Tom and then called my friend Tim Hartung, an architect in New York, who said, “There’s only one person for you to call —Bob Silman.” I called him, and he had someone out here within two or three days. We hired him to verify the calculations. That year Tom retired and I became the director, responsible for dealing with this issue. It was a very interesting and anxious time. We put shoring under the building, but developing a plan to strengthen it and raise the funds took time. And we had to get buy-in from the funding, engineering and architectural communities. But we were able to raise the money needed through the generous support of foundations and others, including internationally. I don’t think anybody realized how beloved the building was.

Q. Can you discuss some of Fallingwater’s famous visitors?

A. 74 percent of our visitors travel a minimum of three and a half hours to get here, including many famous people. Sometimes we know they’re coming through and sometimes we don’t. There aren’t as many rock stars as actors because the actors who are doing a film here are here longer. I wasn’t here when Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie visited. But I was when Tom Hanks, Dennis Miller and Ron Howard came one day. They were touring baseball fields in a bus with their kids.

I was really impressed, particularly by Hanks’ and Howard’s knowledge about Wright and the questions they asked.

One of my first celebrity tours was Peter Falk, who came with his daughter. It was a really funny experience. In those early days, we hadn’t closed the view at bottom of the waterfall, and it could be dangerous. I said, “Be careful—don’t step on any of the wet stone.” He did and immediately slipped and fell on his back end. His pants were soaking wet, but he was a good sport and got up and did the rest of the tour. Then, in the parking lot, he had a flat tire. The whole thing was just like Columbo, and he said, “Oh dear, I don’t know that I can change that.” He was very charming and could not have been nicer, and the guys in the maintenance department were thrilled to help him.

Joan Rivers came through one time, and she sent the guide who took her through a beautiful pair of earrings as a thank you—she couldn’t have been more gracious or nicer.

Q. What has been the best thing about working there? And how will it be leaving it after so many years?

A. Being on the site. Driving to work, you’re going through the prettiest countryside you can imagine. When you enter the site, it’s calming and beautiful. It changes all the time. And the building— walking down and just looking at it. A testament to a true masterpiece is it doesn’t bore you. I continue to see new things about it, new connections. I’ve always sensed the privilege of being responsible for its care. It can be challenging, but it’s really invigorating to work with the best staff, architects, engineers and conservators in the world. We all want to do the right thing for the building.

A lot of what my job entails is looking for what isn’t working, what can be improved, and developing solutions to problems. But when I’m showing the building to someone, I walk down the path and still have the same feeling as I did the first time. It’s a thrilling, wonderful thing. I’m sure I’ll miss it, but it’s time for someone else to have the privilege too. A national search is going on. We’re hopeful that by early March, we’ll have someone on board. I’ll work with that person until they are settled in—but we have a wonderful staff here. I have no worries. I hope to stay involved at least peripherally.

The World Heritage Program, which is part of UNESCO, oversees the World Heritage List, a list of what the international community considers to be the planet’s most significant cultural and natural sites. Most countries have sites on the list, and generally it takes a few tries to get a nomination through. The Wright nomination was first submitted in 2016, and they wanted more information. They were unconvinced that all of the buildings merited inclusion, so we narrowed the nomination to eight.

We have a number of World Heritage Sites in the U.S.—the most famous are national parks, Yellowstone, Yosemite and Grand Canyon. And there are three on the list for architecture—Monticello, the buildings Jefferson designed at the University of Virginia, and Taos Pueblo, which is both an architectural and a natural site. And, I hope, one day soon, Fallingwater. That’s what I’ll be working on.

I’ll be 70 in March, and realizing that life is short, my stalwart and long-suffering husband and I are looking forward to traveling and just being less busy. It seems my whole life has always been around Fallingwater. I’ve spent anniversaries and birthdays here. I’ll enjoy reconnecting with friends, planting my garden and keeping up with it instead of saying, “What the heck happened here?”