As far as shopping plazas go, the Waterworks Mall in Fox Chapel is pretty typical. A Five Guys and a Chipotle. Party City. A Barnes & Noble that still carries… books! A Giant Eagle, the kind that sells groceries, not the feathered kind that have begun to nest again just up the river in Harmarville. The Allegheny flows steadily by as it has for millennia. And birds follow the riverway, up and down and along its shores, despite the impositions of shoppers and trains and cars along Freeport Road. Behind the big box stores are three manmade cement ponds and a chain-link fence. Perched there one afternoon, in stark contrast to all that makes me sad about consumerism and civilization, I saw perhaps the most gorgeous of our native raptors, the American kestrel.

Grey-blue head and wings. Speckles along its cinnamon-washed back and flank. Black teardrop falling from each eye and a white and black face with a tiny, hooked beak. Talons diminutive but not to be dismissed. The plumage of the male is more colorful than the largely subdued colors of the female. American kestrels are tiny falcons, the size of a mourning dove or a blue jay. Patient predators and fast fliers, kestrels wing along at over 35 miles an hour as they attack small rodents, birds, and an astonishing array of critters, from grasshoppers to cicadas to scorpions. Kestrels vacuum invertebrates as fast as they can spot them, scarfing up protein as it hops, flies and crawls. I’ve seen them scanning for prey at the Waterworks, but I’ve also seen them perched over fields in the rural Vermont countryside and nesting in holes under eaves in Manhattan. They’re adaptable, but their populations have declined, by some measures precipitously, over the last half-century due to habitat loss, declining food sources, and pesticide exposure that has impacted reproductive success and prey availability. Kill your dinner with chemicals, and your belly eventually goes empty.

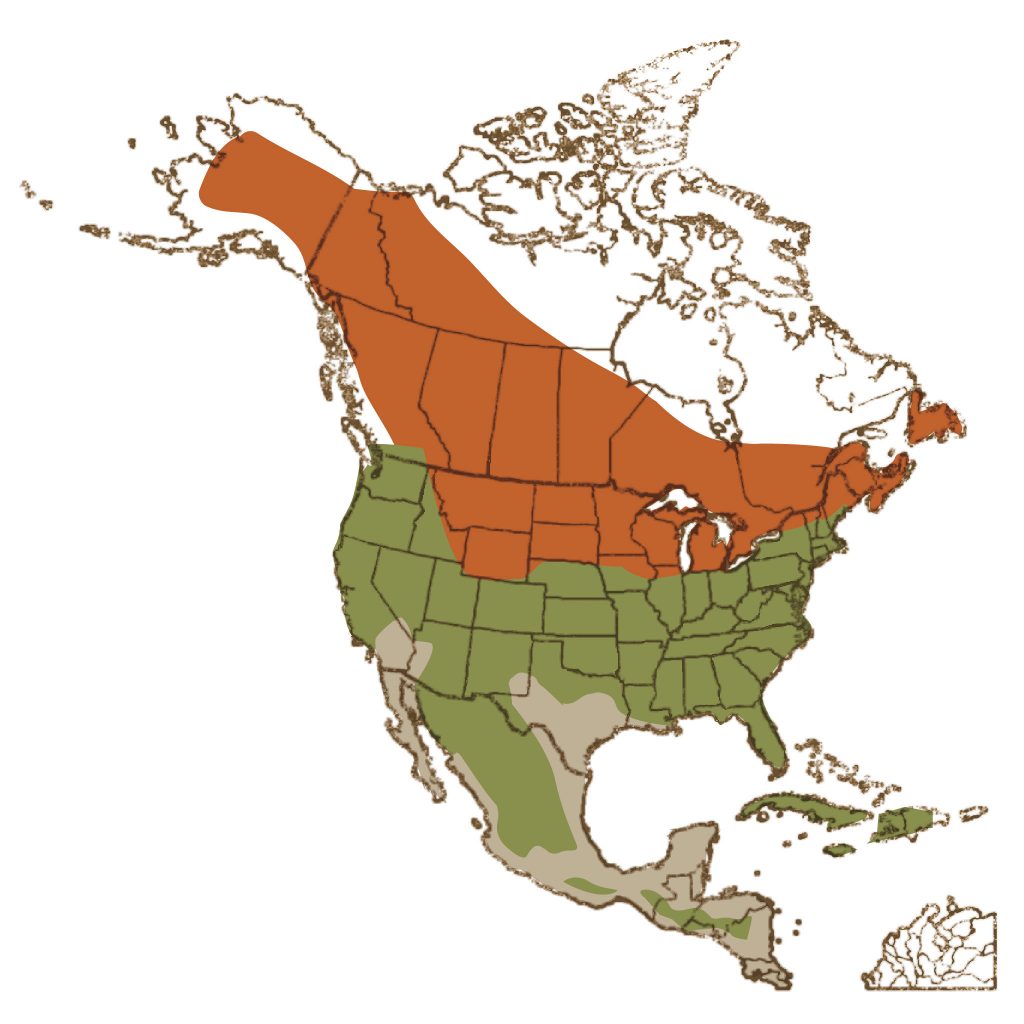

Kestrels nest in existing cavities, sometimes in old woodpecker holes in trees, sometimes in nest boxes, sometimes in a hidden nook under an eave. Males find the real estate and entice the mothers-to-be to give the final say. Four to five eggs, white or brown and flecked or mottled, are incubated for three weeks to a month. Hatchlings spend about the same time preparing to fledge. Some kestrels migrate to South America, while others remain closer to home. It depends on where their natal territories lay.

Most extraordinary is the kestrel’s ability to watch and wait. A keen-eyed kestrel can perch in the same spot or hover above territory until the moment it bursts into fearsome pursuit. Then this wee falcon is all speed and acrobatics and, at the same time, grace. It becomes something archetypal, ideal: the winged hunter. It becomes art, a peerless dancer in the summer air, a reminder that in unexpected places, nature’s beauty can be found.

Year-round

Breeding

Non-Breeding

Email your avian encounters, photos, or questions to PQonthewing@gmail.com.