A Graphic Look at Pittsburgh

Frank Santoro’s “Pittsburgh” is a loving portrait of his Swissvale family, a rich evocation of Pittsburgh’s recent past and a complex exploration of how memory informs the present. After years in California and New York, Santoro now lives in his late grandparents’ home in Swissvale. Internationally revered by his peers, he is one of the most important working members of Pittsburgh’s creative class. A 216-page, exquisitely produced story, “Pittsburgh” is a masterwork of the genre.

But because that genre is the graphic novel, your reviewer feels compelled to post a consumer’s notice: “Read this book three times, at least. Actually, don’t just read, but absorb.”

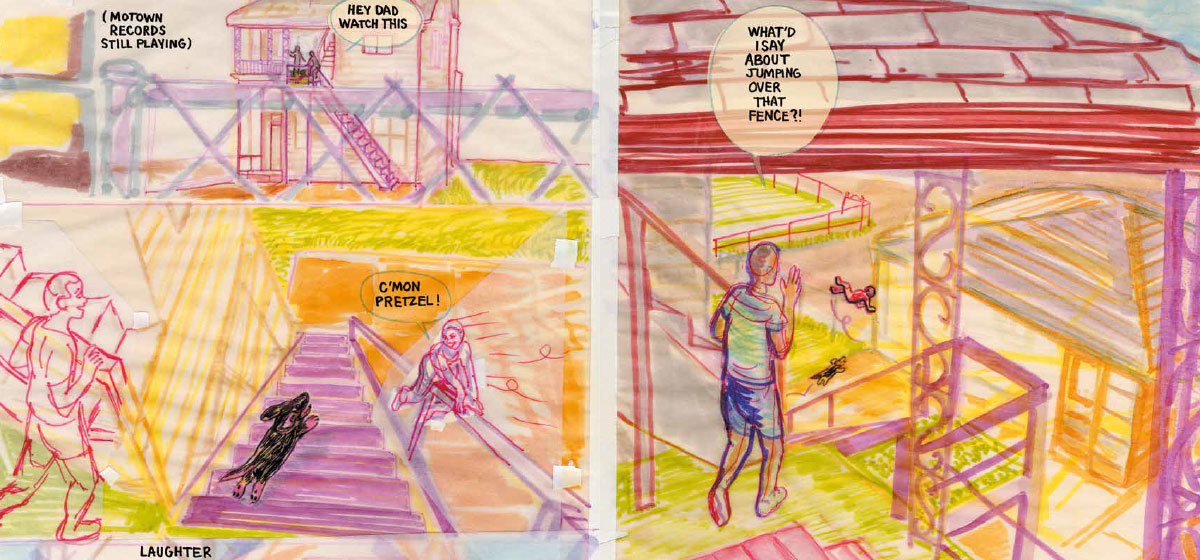

Those guidelines are offered in confession that I—perhaps like you—have an underdeveloped appreciation of the genre. I blasted through “Pittsburgh” in one sitting, and then started again, at a leisurely pace, lingering over details yet not quite in thrall. But over the weeks, Santoro’s images would come bounding into my memory as I was, say, sitting at a stoplight or buttering a piece of toast. The magic of the graphic novel—an evolved comic book, elevated to art—was at work. With each successive viewing, I have found something new.

Santoro made his reputation with “Storeyville,” an epic about two hoboes, and “Pompeii,” about that volcano in the year 79. For the 2011 Pittsburgh Biennial at the Carnegie Museum of Art, he created “Blast Furnace Funnies,” a portrait of Pittsburgh, with the memorable line that “this city is like Pompeii to me, a ruin that used to be.”

“Pittsburgh” is his first purely autobiographical work and, like any memoir worth its salt, is an angst fest. It revolves around the unhappy state of his parents. They have been divorced for 20 years, and not so amicably. They both now work at the same hospital—“the new factory in town,” Santoro notes—but don’t even acknowledge each other if they pass in a hallway. High school sweethearts in the 1960s, they got married as soon as Santoro’s father returned home from the Vietnam War, against the wishes of his mother’s parents. Their divorce took place right after Santoro graduated from high school in 1990 and fled for California. Today, with Santoro back in town, “the only connecting thread between them is me.”

The story shifts back and forth in time. Santoro digs out details from his father’s mother—Mary, a Scot who met Sam Santoro when he was a soldier stationed overseas in WWII—to piece together their Swissvale saga. Sam owned a convenience store on Monongahela Avenue that was a neighborhood hub. Santoro’s mother, Anne Marie, worked there in her youth, helping her keep distance from her hard-drinking Irish family. Santoro’s godfather Dennis, a mill worker, acts as a sounding board throughout. He’s African American, a fact that goes unremarked because it is unremarkable in this close-knit working-class community.

What Pittsburgh readers might find remarkable is that “Pittsburgh” was first published in … France. The European market for sophisticated graphic novels is altogether better than in North America. The French editors encouraged Santoro to work in full color, rather than in less expensive black-and-white because “the book has to take its own shape.” Santoro related that detail in an interview with another hero of the backstory: Bill Boichel of Copacetic Comics in Polish Hill. Boichel, in the comics business for decades, helped encourage Santoro’s work as a teenager and remains a steadfast supporter; he’s thanked in the credits as a proofreader.

In addition to bolstering Santoro’s standing abroad, the publication in French helps the rest of us appreciate the singularity of Pittsburghese. “Geezoman” translates in the French edition as bon sang de bonsoir (literally “good blood of good evening,” but a common idiomatic expression of surprise). “Yinz” is rendered as vous (the plural “you”), defying slang translation, and “jagging” simply becomes a form of teasing.

Some of the most memorable parts of “Pittsburgh” are without words: the interiors of homes from his childhood, a barge along the Mon River, a steel mill set against vivid colors, a Virgin Mary statue in a front yard. They drive the story just as much as Santoro’s sturdy dialogue. They also demonstrate how Pittsburgh has fired the imagination of this determined artist.

In a 2015 profile for a Carnegie Museum publication, Santoro gave writer Matthew Newton one source of his inspiration: “The little postage stamp of land where you are from is the most valuable thing to you as an author,” he observed, quoting the advice that Sherwood Anderson is said to have given William Faulkner. Consider “Pittsburgh” an installment of work that puts Frank Santoro in the pantheon of Pittsburgh’s great creative forces.