A Century of Protecting Birds

My great-grandfather Samuel Feins emigrated from the Old Country, in his case, Russia, in 1899. He came through Ellis Island and then quickly made his way to Massachusetts. Fifteen years later he was firmly established as the proprietor of the New Hat Frame Company of 55-63 Summer Street, Boston. He was a milliner, a hat maker, noting in The Millinery Trade Review that 1916 “would be a big season for satins, velvets, and flowers.” But not feathers.

While feathers and even taxidermied birds had been for many years a way to make a fashionable woman’s hat sing, plumes and whole avifauna as a fashion statement were going out of style. Thanks to Boston Brahmins who took an interest in nature, birds and feathers as decoration would soon be outlawed.

By 1918, the efforts of Boston and New York society ladies and their allies led to the passage of the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the centennial of which has been celebrated in 2018 as “The Year of the Bird.” The Migratory Bird Treaty Act broadly provides that “it shall be unlawful at any time, by any means or in any manner, to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, attempt to take, capture, or kill, possess, offer for sale, sell, offer to barter, barter, offer to purchase, purchase, deliver for shipment, ship, export, import, cause to be shipped, exported, or imported, deliver for transportation, transport or cause to be transported, carry or cause to be carried, or receive for shipment, transportation, carriage, or export, any migratory bird, any part, nest, or egg of any such bird, or any product, or not manufactured, which consists, or is composed in whole or part, of any such bird or any part, nest, or egg thereof.”

It’s worth quoting the language to see how comprehensive it is, a reminder of the seriousness with which supporters and, ultimately, lawmakers took bird protection. With few exceptions, some 800 species are covered by the law. With only minor modification in a century, the act is a keystone in American environmental legislation. Every Pennsylvania bird covered in this column enjoys the protection of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Every species in Pittsburgh is protected by (yes, American Crows!), or purposefully exempted from the act (no luck for European Starlings and House Sparrows, both ubiquitous invasive species imported to the States).

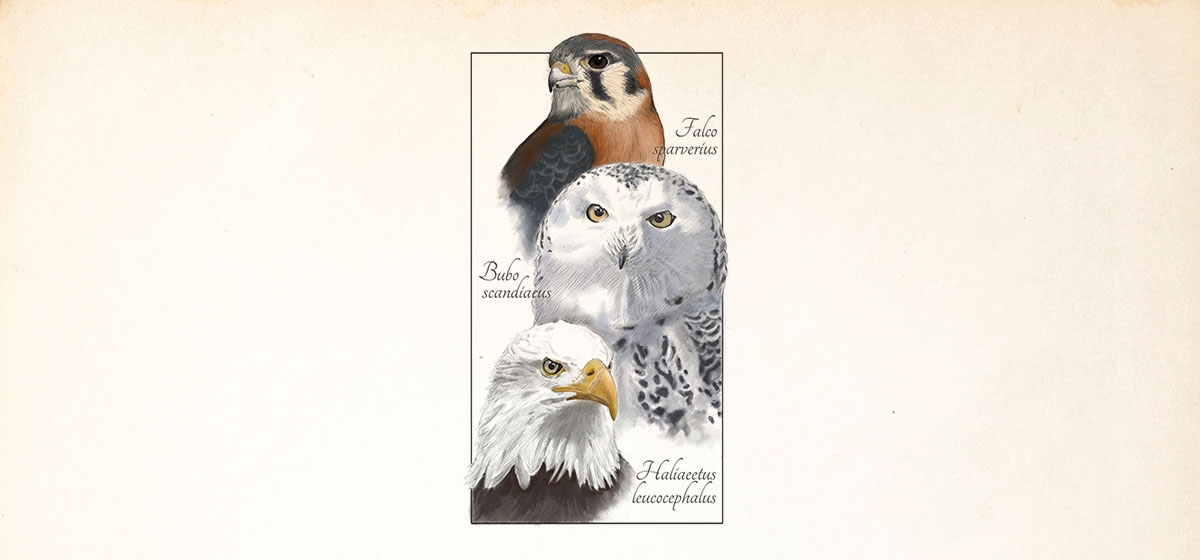

The National Aviary is our local tribute to the wonders of avian life, unique in the nation for being the only non-profit indoor zoo dedicated to birds, recognized by Congress with honorary “national” status, in 1993, and focused on avian education and conservation of birds. If you aren’t one of the 100,000-plus annual visitors to the aviary, I encourage you to make a visit to this feathery gem on the North Side. Five hundred individuals of 150 species large and small call the aviary home, and a walk through their habitats and an examination of the birds up close is one of the best ways to appreciate the living descendants of dinosaurs. Whether you go to see a Bald Eagle, American Kestrel, or Snowy Owl—all birds of Western Pennsylvania at one time of year or another—or one of the many exotic, non-native birds resident in the aviary, developing some “aviphilia” can start this fall with a stop right here in Pittsburgh, perhaps the national capital of birds.