It’s a Book Thing

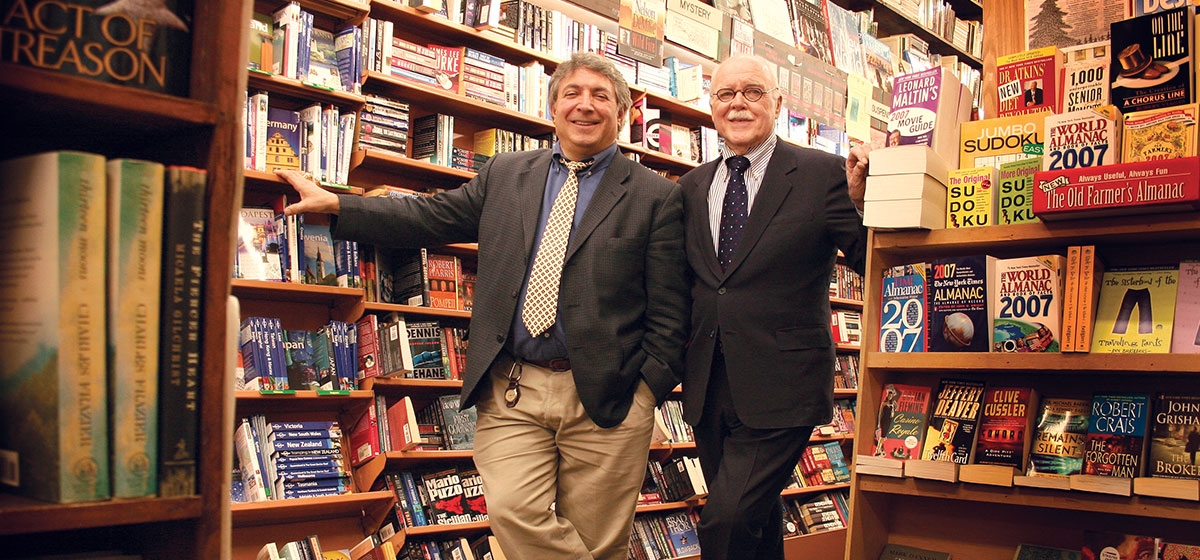

Ten or 15 years ago, a story about Pittsburgh’s “independent” bookstores wouldn’t have made much sense. “When we opened in 1990, there was just the Borders in South Hills,” says Richard Goldman, co-owner of Mystery Lovers’ Bookshop.

Now the Pittsburgh area supports 18 of what Goldman calls “the chain superstores,” doing an estimated 80 percent of the business in book sales. Add to that the rise in the Internet’s role in bookselling over the same era, and the independently owned bookstore emerges as the keeper of smaller presses and more intimate transactions, the hero of emerging authors and eclectic (and regional) tastes, and depending on whom you talk to, an endangered species.

Pittsburgh’s booksellers don’t wonder why they’re in the business. As Jay Dantry puts it, “This is a great business to be in! You meet a heck of a lot of very nice people—they love books, and you love books.” Dantry runs Jay’s Bookstall in Oakland and has since he opened it in 1955.

While Jay’s is known for its display table featuring the latest in literary fiction and non-fiction, Dantry says selling books is the opposite of giving a pitch or putting a novel in someone’s hands.

“Book people already know what they like or don’t like. They come to us to find out what we know.” Dantry hires people who know and like books. And he has kept faithful customers over the years — and their children, and now their grandchildren. He’s also kept faithful employees: store manager Joe Emmanuel has been working there since he was 15, over 40 years now, and Donovan Hughes has been employed by Jay’s for close to 20. A former employee of Jay’s, John Towle, went on to open Aspinwall Books in 2000—carrying on the legacy of the general, retail bookstore known for its well-stocked shelves.

To ride out changing times, smaller bookstores have had to stay on their toes and get creative. Goldman and his wife, Mary Alice Gorman, have built a customer base by getting to know their readers’ tastes and by bringing numerous mystery authors to the Oakmont shop. In addition to year-round readings, signings and even in-store dinners, each May Mystery Lovers’ hosts a one-day Festival of Mystery. In 2006, the festival drew 51 authors and over 400 customers. Goldman says that the store now has an “established reputation with most of the major publishers, but also with authors coming of their own accord—despite the fact that Pittsburgh is not always considered a particularly attractive destination for author tours.”

The Big Idea in Bloomfield has a different idea for staying in business: act like a nonprofit. Without resorting to official nonprofit status, a revolving cast of about 20 young volunteers run this compact two-story bookstore and “infoshop” stocked with left-of-left-wing political literature, and they have regular fundraisers to add cash to the store’s coffers and widen their community. Their books include non-fiction titles you won’t find anywhere else—small press titles of feminist, gay and lesbian, pro-union, or anti-war interests; books about alternatives to capitalism, labor issues or environmental debates. The Big Idea partners with a program, Book ‘Em, to donate and deliver books to local prisoners, and they work regularly in conjunction with the Thomas Merton Center for Nonviolence.

John Schulman, co-owner of Caliban Books, discusses how the Internet has “profoundly changed the business for ‘brick and mortar’ shops.” He explains that in very “Web savvy” areas such as the Bay Area, this change has led to the closing of many bookstores. “But in Pittsburgh, people actually prefer the communication of across-the-counter buying. We benefit from Pittsburgh’s ‘retro’ qualities.” He credits the cyber-changeover with the ability to obtain much quicker and sometimes more accurate information for pricing and cataloging the rare and used books that he and his wife and partner, Emily Hetzel, offer.

Caliban now does 40 percent of its sales online, and Schulman claims the percentage could keep increasing, depending on how much labor they put into that side. “But there are a lot of reasons for us to keep the shop open. I believe that bookstores are an important part of city life,” Schulman says. “I wouldn’t want to live in a city that didn’t have any used bookstores, so I feel that we’d be letting a lot of people down if we closed as a storefront. As long as it makes some money, it stays.”

Neil and Beverly Townsend of Townsend Booksellers, just off Craig Street, tell the story of how they decided to make Pittsburgh the site of their used bookstore: “We came here from Northern California, and just on a visit we bought box loads of books—we realized that there are simply a great many books in Pittsburgh.And at the time [1990] we saw that the neighborhood of Oakland was very underserved for bookstores.” The Townsend family became a true Mom and Pop shop when they bought a building on Henry Street and made one floor their home, several rooms their warehouse and the ground level their bookstore. They opened for business in December of 1991.

Beverly Townsend continues, “There are all these big old homes in Pittsburgh—they’re often storing a wealth of old books. But when people call us, I’ll ask, ‘Do you keep them in the basement?’ We don’t usually want to see those.”

None of these booksellers seems to regard the others as direct competition. Eljay’s and City Books are used bookstores just a few blocks apart on Carson Street. But Eljay’s co-owner Frank Oreto says that, in the used book world, “No one steps on your business. In retail, everyone’s trying to sell the same item, so some fairly basic rules of supply and demand apply. But second-hand stores have got really, really varied inventory. Your customers tend to find you.” Eljay’s is known for a little of everything, but especially for science fiction, fantasy, history, art, the Beats and any fiction that’s a little outre. Oreto thinks, “the more [used book] stores you have in one area, the better. You just get more people shopping for used books.”

In the independent book world, Oreto doesn’t seem to be alone in his thinking. Mystery Lovers sends authors to sign books at Jay’s, and Jay sends extra books to Mystery Lovers if they need more for an event. Caliban recommends people to Townsend’s. Jay Dantry understands that especially when Stonewall and Squirrel Hill Books were open, people used to make a loop, book shopping through Oakland, Squirrel Hill and Shadyside. “Some guys like to go to hardware stores on Saturday mornings, other people like to go to bookstores.”

Pittsburgh also supports three shops whose stock focuses on comics, all inside the city limits. They are Copacetic Comics in Squirrel Hill, Eide’s Entertainment in the Strip District and Phantom of the Attic on Craig Street. Phantom has been an Oakland comic book and games store since 1983. Jeffrey Yandora, owner since 1990, talks about his small business as if it’s a hunter-gatherer existence. “It’s a constant balancing act to see if I can pay off the bills and also still buy the new books, the new merchandise that is the backbone of my store. That is the business—if I’m not finding what’s new and putting it out for my customers, then I’m not in business. But it’s certainly not the American profit model as we know it.”

Yandora says the recent rise of the graphic novel (a book-length, perfect-bound, comics-style story) has been a boon to his business. “Movies like American Splendor and Ghost World, and locally the Carnegie International, which featured [comic artist] R. Crumb, have helped bring on the current fervor in comics. And the graphic novel form makes it something adults might want to read.” He feels especially grateful for the diverse customer base that nearby Pitt and CMU bring, allowing Phantom to offer the newest in independently published comics, Japanese animation or the latest issue from old standbys DC or Marvel Comics. “We want to be a reader’s store. I’m not interested in judging or minimizing any one genre. I’m also not terribly concerned with the weird stock market that some collectible comics stores can be.”

Trade book buyer Russell Kierzkowski has been working for the University of Pittsburgh Book Center since 1966. He says the Book Center benefits from the captive audience and the inevitable foot traffic that the campus location brings. “Our customers are the staff, faculty and students of Pitt. And our focus is on supporting and listening to the university community first—we exist to meet their needs.” For Kierzkowski, no campus event is too big or too small for him to send someone with a table of books to sell, and a professor with a new title gets the royal treatment when having a book party, signing or lecture at the Book Center.

The Book Center is one of a dwindling number of college bookstores in the country that has not been bought out by Barnes and Noble. “Faculty who transfer to Pitt are often very grateful,” observes Kierzkowski, “because the chains are not responsive to the needs of the academic community they’re supposed to serve. Anything that is not going to be big profit for them, they tend to ignore.”

Copacetic Comics is a postage-stamp-sized shop neatly crammed full of comics, art books, literary fiction, children’s books, select DVDs and periodicals. Owner Bill Boichel is a comics artist, writer and former filmmaker with a passion for art, photography, literature and cinema. His shop reflects and benefits from the scope of his interests and knowledge. Boichel echoes Kierzkowski’s sentiments about the superstores’ “big profit” motivations and says he has used this to inform his business model. “I made a choice to edit out all the ‘noise’ and concentrate on putting my expertise to use in selecting works of higher quality and, in addition, to cater directly to the interest constellations of my customers.”

Jerry Farber and his wife, Tara McLarney, ran Stonewall Books in Shadyside for its final decade. “Our customers came to us because we knew more than most anyone about books. They could trust our taste and our judgment,” Farber says. He now lets someone else worry about the overhead: for the last 10 years he’s been happily employed as the book buyer for all four Carnegie Museum shops.

Stonewall opened in the late 1960s and closed in 1995, soon after Barnes and Noble came to Squirrel Hill. Farber fears, “There may be a whole generation growing up without a sense of what it’s like to walk into an independent bookstore.”

Dear readers, let’s hope not.