Is a house private or public? Like any compelling opposites, each really only exists with measured dollops of the other. Choices of how to eat, sleep, bathe and relax are very private. Yet the artistic movements or common practices inflecting those selections are very public—from publications and exhibitions to the sprawling possibilities of the design and decoration marketplace. Maybe a household even intends to influence and not simply follow culture.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”367″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]How else could you discuss the Alan I W Frank House on Woodland Road abutting the Chatham University campus? Completed in 1939 to designs by iconic architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, it has largely steered clear of precisely those books and exhibitions by which its architectural style and practitioners achieved fame. The Frank House has had some notable local press just recently, but only now is it the subject of a nationally distributed book, “Alan I W Frank House: The Modernist Masterwork by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer” from Rizzoli International Publications.

Alan I W Frank, the book’s primary author and current resident, was 5 years old with two older sisters when his parents Robert and Cecilia Frank commissioned Gropius and Breuer to design the house. The elder Frank was a third generation Pittsburgh industrialist, engineer and philanthropist whose newly formed Copperweld Steel was a growing enterprise. Gropius had just delivered a particularly persuasive lecture in Pittsburgh, and the Franks considered him the world’s leading architect, beyond likely comparisons to Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe or Le Corbusier, perhaps Rudolf Schindler or Richard Neutra.

“Society needs a good image of itself,” Gropius declared. “That is the job of the architect.” He founded the Bauhaus in 1919 and designed its building in Dessau, Germany, in 1925 with Adolf Meyer. The facility, curriculum and architectural style idealized close engagement with factory production. The austere but elegantly proportioned Bauhaus building transcends its 1920s earnestness to remain a relevant design exemplar to this day.

Breuer, meanwhile, revolutionized furniture design at the Bauhaus in the 1920s. His Wassily chair is still a mainstay in architects’ offices, while his bent steel Cesca is still so common as to seem generic. His architecture remains in renewed or perpetual fashion with today’s vogue for the Brutalism of the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1939, though, the pair, having fled the Nazis and landed as Harvard design faculty, were in a lull of architectural practice that would only rebound dramatically after World War II.

The Frank House was a singular opportunity. An unconstrained budget allowed realization of a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art in landscape, architecture and industrial design—that their earlier European social housing projects could not fathom. And Robert Frank was a uniquely expert client, whose frequent multi-page, single-spaced letters per week during design and construction suggested specific technical innovations for the house. Industry-minded Gropius had declared that “architecture begins where engineering ends.” A close collaboration suited all parties.

Very much “free of untruths or ornamentation,” in Gropius’s phrase, the Frank House retains much of the geometric severity of the European projects. Yet it is transcendently luxurious. Sprawling, with 12,000 square feet of indoor space and 5,000 more of outdoor terraces, it houses nine bedrooms and a full 13 baths, as well as a swimming pool.

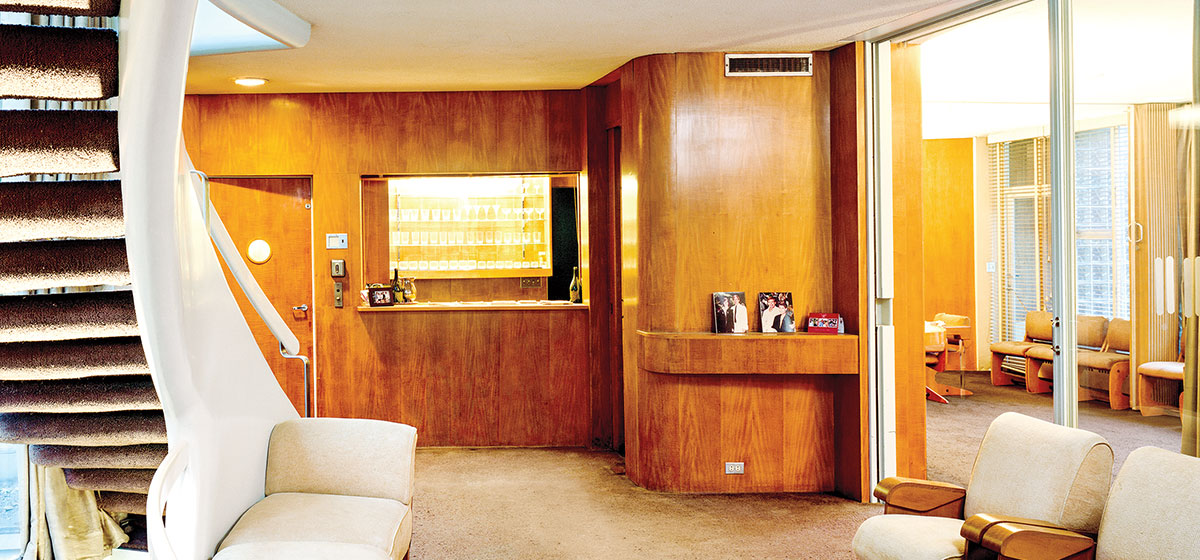

Its cantilevered curved staircase bows slightly outward, giving the house its expressive multi-story window. Curved travertine “wings” of the fireplace organize sequences of spaces, nurtured with well-placed finishes in hardwoods and custom fabrics, including work by Anni Albers. Renowned designer of mass produced pieces, Breuer here produced by far his largest collection of bespoke furniture as well as hardware and fixtures.

Once an editor of the Harvard Crimson, Alan Frank remains a lucid and engaging writer. His essay is a fond recollection of the house’s construction as well as an intimate and precise tour through each room’s appointments and details. Energy saving mechanical systems, electrical lines in conduit with mercury switches, as well as a Copperweld lightning rod system are reminders that Robert Frank’s technology-driven optimism was founded in long-term reliability.

The Franks also hosted many guests, from neighbors who enjoyed the pool to hundreds of distinguished visitors in culture, civic affairs and the performing arts. However, with the exception of one article in a 1941 issue of Architectural Digest with no identifying name or location, the house went for decades without being published, even though it was a culminating example of work by two of the world’s most influential architects.

Robert Frank did not want to publicize the house. “He didn’t want people wandering up the driveway and taking pictures,” Alan recalled in a recent public forum at the Carnegie Museum. Fortunately, remarkable vintage photos by Ezra Stoller and newer ones by Richard Barnes do the job for you.

J. Carter Brown, former director of the National Gallery of Art, whose own family commissioned a similarly exceptional modernist masterpiece from architect Richard Neutra in 1936, once called the Frank House “America’s crown jewel” before his passing in 2002. And research by architectural historian Barry Bergdoll, one of the book’s contributors, along with Kenneth Frampton and Charles Birnbaum, has led to increasing interest in and acknowledgment of the house’s importance.

These additional essays seem like warm-ups for potentially much deeper inquiries into the house’s considerable archives, as well as the discussion of where the Frank House stands in relation to the history of Gropius, Breuer and the Bauhaus tradition. Meanwhile, this first book is a must-have for anyone who cares about Gropius and Breuer in Pittsburgh, and in modern architecture internationally.