Hard to Swallow

It started with a cough and the need to clear her throat whenever she ate. Eventually, swallowing became more difficult—and even dangerous—for Patricia Grimm, 63, of the North Side. “I’d be at Red Lobster eating a salad or in the car eating a hamburger and I’d start choking,” she says. ”When you can’t breathe because you have something stuck in your throat, it is the most horrific feeling ever.”

Grimm is among an estimated 10 million Americans evaluated each year for swallowing difficulties, according to the National Foundation of Swallowing Disorders. Although not a word that is top of mind for most of us, dysphagia (the medical term for difficulty swallowing) affects a staggering number of people—as many as 22 percent of those over 50. It can be the result of weak muscles, stroke, head and neck cancer, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and many other diseases. It can even develop from undertreated heartburn or GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease).

Grimm’s dysphagia was caused by a rare condition: food getting caught in pouches (diverticula) along weakened sections of her esophagus (swallowing tube).

Because dysphagia cuts across so many diseases, it is often under-diagnosed and sometimes not picked up until a person ends up malnourished or with recurrent pneumonia (caused by food or liquid leaking, sometimes silently, into a person’s lungs).

Just a few decades ago, the swallowing process was not well understood and little could be done beyond prescribing unpalatable pureed foods and thickened liquids. But today, experts can pinpoint the underlying problem and offer many strategies—from high-tech laser surgery to low-tech swallowing therapy.

“There has been so much forward movement in this field. So much has happened in the last decade, in terms of technology in diagnosing and treating people who have swallowing issues, especially for those who’ve had a stroke or have problems related to aging,” says Dr. Blair Jobe, an esophageal surgeon and chair of Allegheny Health Network’s Esophageal and Lung Institute. He adds, “This issue is so widespread, and we swallow so many times a day that when you don’t have a good swallowing mechanism, your quality of life goes down very quickly.”

In the fall, AHN opened the Voice, Swallowing and Nutrition Center at West Penn Hospital, touting it as the only center on the East Coast to bring to one clinic setting esophageal surgeons, ENT (ear, nose and throat) physicians, registered dietitians, speech-language therapists, nurses and diagnostic tools.

More sophisticated than you think

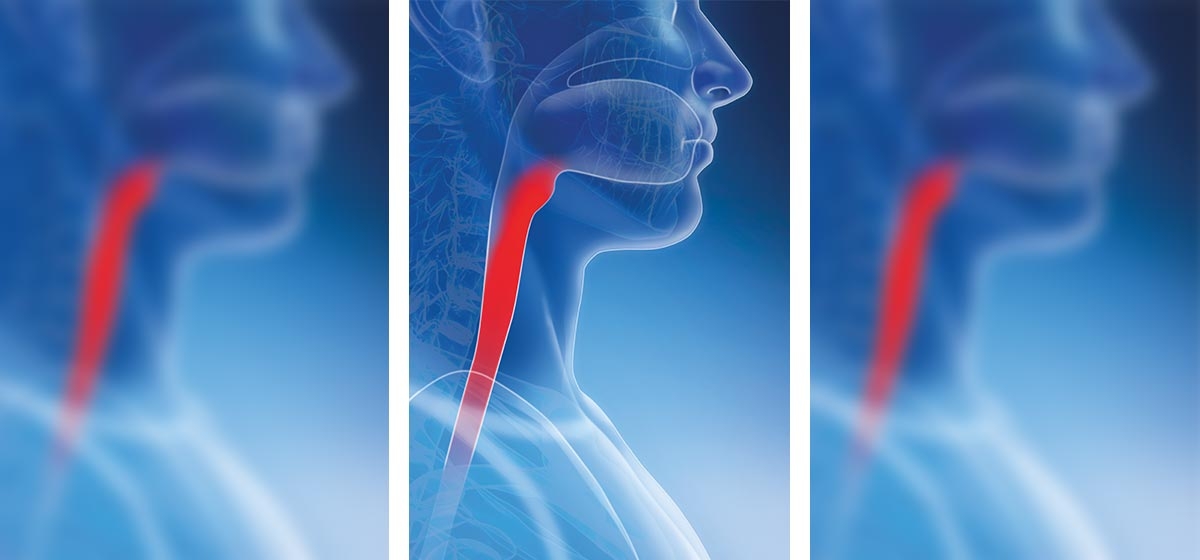

For most of us, swallowing is effortless and something we do hundreds of times a day. Despite this apparent simplicity, swallowing is considered to be one of our most complicated neuromuscular activities: It requires the use of 26 pairs of muscles, five cranial and three cervical nerves, along with several central nervous system processing levels. Such complexity leaves swallowing very susceptible to impairment.

“When you do it all the time, without thinking about it, swallowing seems like a reflex. But it’s very much not a reflex at all. It’s a patterned motor response to whatever you’re swallowing and your cognitive ability to recognize what you’re swallowing,” says Dr. Libby Smith, an otolaryngologist (ENT doctor) and director of the Swallowing Disorders Center at UPMC.

Doctors such as Smith can offer surgical or outpatient therapies that include Botox injections (yes, the same thing used to smooth facial wrinkles) and balloon dilation to open up a tight swallowing tube. “Botox injections are falling a little more out of favor because dilation works so well and is by far the more common procedure for otolaryngologists or gastroenterologists,” she says.

Most causes of dysphagia can be treated without surgery. “Just like what you’d do with arms and legs, swallowing clinicians can do a kind of ‘physical therapy’ for the swallowing mechanism,” says the University of Pittsburgh’s James Coyle. Few focus on swallowing as much as Coyle; he’s a speech-language pathologist, longtime dysphagia researcher, teacher, and practitioner as a board-certified specialist in swallowing and swallowing disorders, and professor in Pitt’s Department of Communication Science and Disorders, ranked 7th in the nation by U.S. News and World Report for graduate programs in speech-language pathology, a field high in demand (read more below).

One of Dr. Smith’s dysphagia patients, an otherwise healthy older woman, was skeptical of swallowing therapy. But after two sessions, she was able to go back to eating at restaurants, Dr. Smith says, noting, “As we age, our swallowing mechanism also ages. It’s not uncommon for a person to break a hip and all of a sudden not be able to swallow any more. It’s the deconditioning associated with the hospitalization that can push a person over the edge to a clinical swallowing issue.

“Eating is so fundamental to who people are,” she adds. “When you think about all of the medical ailments that a patient has to be dealing with, people often focus on the swallowing because it’s so important to our psyche. It’s the way we live our whole lives.”

Not just for talking

Many people don’t realize that speech-language pathologists are the main providers of care for those with a swallowing disorder. Because these experts closely study the biomechanics of the mouth and throat, “a speech-language pathologist is the best person to know about the swallowing process,” says Caterina Staltari, director of clinical education in the Department of Speech-Language Pathology at Duquesne University. “As an accredited program, we assure that our students are provided with opportunities to meet the knowledge and skill standards across our ‘Big Nine’ disorders, which includes dysphagia,” she adds. This is a significant change, she notes, as dysphagia was not part of her coursework in the 1980s at Pitt’s speech-language pathology program.

When Srividya Ravishankar, a certified speech-language pathologist with Ohio Valley Hospital in McKees Rocks, goes to see a patient, it’s not unusual for her to hear, “Why do I need a speech therapist? I talk just fine.” Ravishankar began her career working with children but now enjoys helping older adults. About 80 percent of her patients have a swallowing issue. Experts like Ravishankar can train patients to protect their airway with simple methods, including turning their head a certain way when swallowing. “One of the biggest things is silent aspiration, which nobody can detect at the bedside,” she says. “The patient is not sensing anything going wrong. You think he’s swallowing fine but there’s a little leak into his airway. It’s pretty common, especially among those with stroke or neurological disorder such as MS [multiple sclerosis] or ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis].”

Examining how food gets from the mouth to the stomach is key, as sometimes a person will point to their throat with a feeling that food is getting stuck, Dr. Smith says, but the problem is farther down in the esophagus. A diagnostic swallowing exam typically involves using an X-ray to get a video of the swallowing process or placing a fiberoptic scope down a person’s throat.

James Coyle is working to develop a simple hardware-software system that anyone, even a patient’s family member, could hopefully use to uncover a swallowing issue. He is overseeing the clinical aspects of National Institutes of Health-funded research along with his Pitt colleague, Ervin Sejdic, in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “We’re working on a project to determine whether sounds and vibrations coming from the throat during swallowing contain information that point to dysphagia,” Coyle says. Their research team is analyzing 4,000 swallows from 300 research participants and creating computer algorithms to interpret the electrical signals and hopefully match what a speech-language pathologist would observe on an X-ray video.

Later this year, Sejdic and Coyle hope to secure a third NIH grant so they can start testing the system on patients with suspected dysphagia. “The beauty of such a system is it would be less invasive than an X-ray, easily deployable, and doesn’t require a lot of knowledge to use.”

Other exciting dysphagia research is testing the effectiveness of magnets to stimulate stroke-damaged parts of the brain. Up to 50 percent of stroke patients develop dysphagia.

Electrical stimulation of the swallowing muscles was introduced more than two decades ago. But Coyle cautions that there is not yet enough good scientific evidence to back up claims that it is effective. “The jury is still out on the efficacy of electrical stimulation for dysphagia treatment.”

Swallowing safely again

When Patricia Grimm started to have trouble with choking and spitting up food, she was careful to eat small meals, chew thoroughly, and avoid tough foods such as steak. Still, she never knew when she would end up choking and started to lose weight on her already small frame. Fortunately, she found a cure with surgery performed by AHN’s Dr. Jobe to remove the pouches in her esophagus. After a month of soreness and a strict diet, Grimm was back to eating normally. For a year now, she says, “I have not choked. It’s been a remarkable recovery. And all of the issues that I did have—the coughing and always having to clear my voice—all went away. I’ve been blessed with having remarkable doctors.”

Looking for a new career?

Job prospects look bright for speech-language pathologists. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that 28,900 jobs will open up before 2024, spurred largely by an aging baby boomer generation.

With a median salary of $73,410 and 1.8 percent unemployment rate, speech-language pathology ranks 20th among best health care jobs by U.S. News and World Report. “Our students are employed by the time they walk down the aisle at graduation. They are finding jobs in school or medical settings,” notes Caterina Staltari, director of clinical education in the Department of Speech-Language Pathology at Duquesne University, touting itself as the nation’s first five-year, accelerated program that guarantees students a bachelor’s and master’s degree.

Fascinating field of study

Swallowing didn’t become a focus of study until the 1980s, says the University of Pittsburgh’s James Coyle. Since then, science has uncovered some interesting findings:

Drinking a liquid is an entirely different process than swallowing a chewed solid food.

The muscle output of swallowing is impacted by the texture, temperature, flavor and other sensory aspects of what’s being eaten.

Thickened liquids can prevent aspiration (particles leaking into the lungs) in some people. But they are over-used and people tend not to like a diet of thickened liquids so are at risk for dehydration or malnutrition. Learning to swallow differently can allow patients to continue to eat and drink foods and liquids that they enjoy.

Who needs a swallowing exam?

It’s important to be evaluated for a swallowing disorder if you have:

- Trouble swallowing (sensation of food and medications sticking or moving slowly in the chest)

- Constant feeling of a lump in the throat

- Coughing or choking with eating or drinking

- Recurrent pneumonia or other respiratory tract infection

- Weight loss