Most of the women who trust their children to Jamie Tabb’s cottage childcare business in Turtle Creek are struggling to get by under circumstances she knows well. She’s a single woman raising children on her own, as they are. She’s been employed and poor at the same time. She’s had to allow limited public transit schedules to determine where she could go and when. And she knows what it’s like to long for the peace of mind that having stable, affordable housing offers.

“When I was a teen mom and going to school and working, it was so much to handle,” said Tabb, 25, the mother of two boys and a girl ranging in age from 4 to 9 years. “I’d take the bus. I went to school in Braddock Hills and worked Downtown. I’d have to leave early because it took an hour to get Downtown. I worked at night and no day care stayed open late.”

She never earned enough working part time or full time at a bank, a nonprofit and as a medical assistant that she didn’t worry about minor expenses. Tabb quit her Downtown job last year after her 9-year-old daughter was diagnosed with leukemia. She opened a day care business in her home, where she could better manage her life and family. “I’d been living paycheck to paycheck. I had three kids and medical problems. I was going to work with that on my mind. I was going to Children’s Hospital a lot. That’s two buses— $3.50, there and back. It just got to be too much. I know what these moms are going through.”

No data point better illustrates what such hardship means to the region than this: In Allegheny County, single women with families account for 77 percent of the households living in poverty.

City and suburbs alike

Single mothers’ vulnerability to living a life of poverty was not lost on The Pittsburgh Foundation, which identified them as a target population when it launched “100 Percent Pittsburgh,” its initiative to explore strategies for enhancing the opportunities of those left out of the region’s economic resurgence. The idea is to conceive and support solutions that are informed by community conversations, including discussions with nonprofits and others who help women work through their challenges and single women with children themselves, who know better than anyone what they need to more fully participate in the Pittsburgh economy.

Foundation officials found plenty of evidence to confirm that these women should be among the populations on which the initiative will focus. There are stark national and local data on key quality-of-life issues from income to housing, and volumes of research into the roots of the poor outcomes they disproportionately experience. And there is anecdotal evidence, such as the emergence of the nonprofit Diaper Bank of Western Pennsylvania.

“This is where we are,” said Jeanne Pearlman, The Pittsburgh Foundation senior vice president for program and policy. “We have to have a nonprofit to get diapers for moms who can’t afford them for their babies.”

And then there is the scope of the problem. High rates of single women who are raising children and living in poverty are found in cities and suburbs alike. And it is not a local phenomenon.

More than 28 percent of the U.S. households headed by women had poverty-level incomes in 2015, or about 4.4 million households, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Among married families, the poverty rate is less than 6 percent.

In the Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area, the poverty rate among women head of households rose 15 percent between 2000 and 2012, according to an Urban League study.

More than half of those households are found in Allegheny County, the region’s urban core. But the largest increases are seen in the six surrounding counties. In Butler County, for example, the number of single women with children living in poverty increased 52 percent; in Westmoreland County, it rose 40 percent; in Beaver, 36 percent.

Some 500 families are enrolled in a regional group of family support centers, offering home nursing visits, education and employment support services. And about 95 percent of those families are single women raising children 5 years old or younger. Most have poverty-level incomes as defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The centers are part of a network called Family Care Connection, a public-private initiative created nearly two decades ago to help stabilize low-income families and prevent young children from experiencing poor outcomes down the road.

It’s not finding employment, but the quality of the job that is the issue for many of the women, said Charlotte Byrd, who manages Family Care Connection. “These parents are working, but at such a low wage that most are still in poverty.”

Women raising children on their own face an uphill climb for a number of reasons. Theirs is the only income. And there’s no spouse to help raise the children and share the load of other household responsibilities. A poverty- level income typically exacerbates whatever other challenges they face, leaving them more susceptible to crisis and limiting opportunities for improvement.

“It’s not finding employment, but the quality of the job that is the issue… These parents are working, but at such a low wage that most are still in poverty.”

— Charlotte Byrd, Family Care Connection

‘Everything is a struggle’

Mary Carey, a 47-year-old single mother, is an art and cultural facilitator at the Carnegie Library in Braddock. She considers the job to be the most fulfilling she’s ever had and one the library offered her after years of volunteering there. Most recently, she’s worked with the Braddock family support center to launch a grant-funded program that she conceived to prepare young, low-income men in the neighborhood to succeed in adulthood.

She also works side jobs as a notary and as a jitney driver to support herself and her 12-year-old son. And she relies on a public subsidy to cover a portion of her housing costs.

Her life became one of limited opportunity after the birth of her first son, who is now 31 and living on his own. He was 6 when Carey was convicted of assault at the age of 22, giving her a record that complicated everything from building a career to finding affordable housing and childcare. She’d been trained as a home health aide, for example, but those jobs dried up given her felony conviction. She turned to a temp agency, but the pay was light and her assignments were so sporadic that she couldn’t log the necessary hours to be eligible for a state childcare subsidy.

Carey’s mother, who was battling cancer at the time, took them in, providing the home and childcare Carey couldn’t afford. “As long as she knew I was working or going to school, she never said nothing,” Carey recalled. “If I didn’t have her to watch my son while I looked for work and went to work, I don’t know how I would have been able to get along.”

Childcare and transportation are the top barriers to economic security for single women with children, according to a Women’s and Girl’s Foundation survey of families enrolled in Allegheny County family support centers. Finding employment ranks a distant third.

Affordable childcare is particularly problematic. The state’s childcare subsidies require women to be working steadily or going to school, and high demand often means waiting lists for the limited funds.

Working off-hours narrows childcare options. Childcare centers accommodating evening and early morning hours are scarce. But the demand is such that when Tabb talks of expanding her childcare business, she envisions a network of ’round-the-clock centers as her way of retiring by age 30. “I know what it’s like to be a parent and not work 9 to 5. It’s hard to find daylight-hour jobs unless you have a degree. A lot of people working in restaurants, nurse’s aides, teen moms—they’re working night shift.”

Off-hour work also complicates transportation when the only options are public transit systems that scale back routes and hours in the evening and on weekends. It’s an issue for single women with children in Allegheny County, which operates the region’s largest public transit system. It’s more challenging in surrounding counties, where public transit is underdeveloped and single women in poverty are more likely to need to take on the additional expense of owning a car.

Affordable housing is another challenge common among low-income families. It’s the chief reason why single women enrolled in Family Care Connection centers tend to be highly transient, Byrd said. “Some women have subsidized housing. But others don’t, and rent has gotten so high it’s ridiculous. They spend most of their wages or benefits on rent.”

The average fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment has increased 29 percent since 2005 to stand at $827 a month in the Pittsburgh MSA, according to U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development data. At that rate, someone with a minimum-wage job would need to work 26 hours every week just to cover rent.

Nearly 82 percent of renters in southwestern Pennsylvania who earn less than $20,000 a year spend at least 30 percent of their income on housing. HUD considers such households to be “cost burdened” and at risk of being unable to afford other basic necessities, such as food, clothing, transportation and medical care. Only 2.5 percent of renters earning $75,000 or more spend 30 percent of their income on housing.

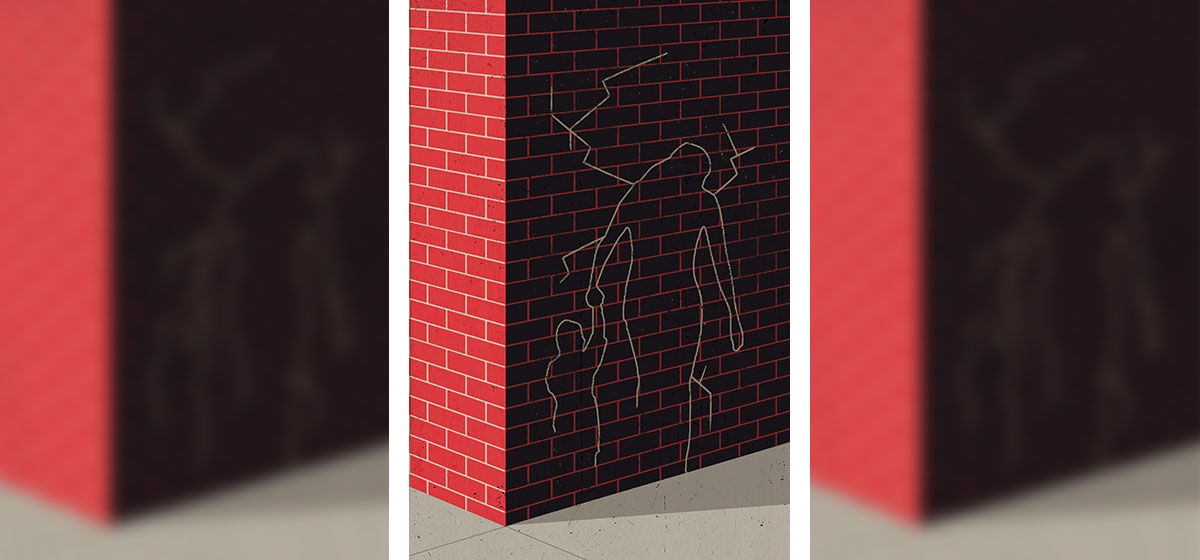

Over the past 25 years, an increase in the number of U.S. homeless families has coincided with an increase in single-parent families, most of which are headed by women. About two-thirds of homeless women live with minor children and 80 percent of those children are younger than 11, a study by Princeton University and Columbia University researchers finds.

“When you don’t have resources, everything is a struggle,” said Marc Cherna, director of the Allegheny County Department of Human Services.

Easing that struggle has long proven to be difficult. Most families that Cherna’s department serves face multiple challenges, which requires a holistic approach to human service delivery.

No county does that better than Allegheny, for reasons that range from local political support and innovation to the willingness of local foundations to create a fund specifically for exploring better ways of integrating services. Still, barriers remain. The most difficult are the restrictions on how money allocated by scores of government agencies can be spent. The lack of flexibility discourages a holistic approach and often leads to treating symptoms rather than causes of family distress.

Far-reaching consequences

More than their well-being is at stake when women struggle in poverty. “As fare mothers, so fare their children,” said The Pittsburgh Foundation’s Pearlman.

Opportunities to start school ready to learn elude large numbers of low-income children. An estimated 64 percent of them lack access to quality pre-kindergarten programs, according to Pennsylvania’s State Department of Education.

The outcomes of children whose families receive human services offer a glimpse of the impact poverty has on their lives and prospects. Poverty is the most common circumstance shared by families involved in services ranging from mental health and drug and alcohol treatment to housing assistance and child welfare protection. Evidence suggests children of these families face significant challenges and a greater risk of poor outcomes, particularly in school.

Public school students involved in human services are much less likely than those who’ve never been involved to carry a 2.5 grade point average or higher, Allegheny County Department of Human Services and school district data suggest. They are much less likely to be proficient in math and reading as measured by state standardized tests. They also have higher rates of chronic absenteeism, which increases the likelihood of underperforming in school.

In public schools countywide, for example, 62 percent of students receiving human services were absent at least 10 percent of the school year in 2014. In the Pittsburgh Public Schools, students involved in human services, such as the public welfare and child welfare systems, accounted for 58 percent of the students who missed at least 20 percent of the school year in 2012. Of those, only 14 percent had a 2.5 GPA or higher.

Such outcomes tear at one of the strongest desires shared by most of the single women with children Byrd said she encounters at the family support centers she manages. “They want their children to do better than they are doing. They want their children to be ahead of where they are themselves.”