You don’t need to love football in order to enjoy Art Rooney Jr.’s glowing tribute to his famous father. “Ruanaidh: The Story of Art Rooney and His Clan” is first and foremost about people—the odd and irascible, the magnificent and flawed, the drunk and devout—in the orbit of one of the greatest “people persons” ever to grace our city, Steelers patriarch Art Rooney.

The clan of the subtitle refers not only to Rooney’s five sons, but also to his siblings, spouse, in-laws, nieces, nephews, friends, fans, employees and hangers-on; in short, all who hailed Art Rooney as “The Chief.” It’s a terrific story and a worthwhile read under any circumstances, but as background to the Rooney family drama recently played out in the national media, it is fascinating.

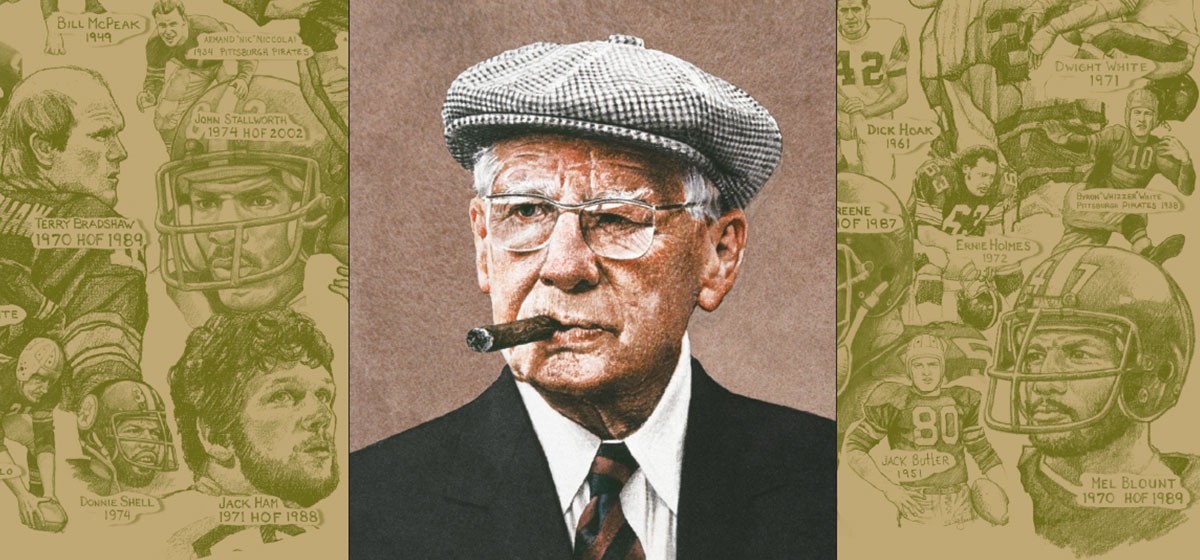

Arthur J. Rooney (1901–1988), the son of a saloon keeper on Pittsburgh’s North Side, was a quick-witted, street-smart operator blessed with prodigious athletic ability, abiding religious faith and a can-do attitude. His early career conformed to the Horatio Alger model of the day: a youth with luck and pluck who attracted the attention of a successful mentor. In Rooney’s case, that man was Republican State Senator Jimmy Coyne, who made Rooney his lieutenant in the predominantly Irish-Catholic First Ward. From Coyne, he learned the importance of establishing connections, trading favors and making people feel special—an activity at which he excelled. Rooney supposedly had the ability to recall the name of everyone he ever met, and he maintained a postcard correspondence with hundreds of people throughout his life. He was famous for attending wakes and funerals nearly every day to pay his respects to acquaintances, their relatives and sometimes even complete strangers.

As Rooney’s reputation grew, so did his business interests. As both a sportsman and an entrepreneur, he had fingers in many pies: football, of course, as well as boxing, baseball, bootlegging, gambling, construction, real estate and horseracing—his other great talent. A couple of big wins at Saratoga during a single week in 1936 provided the foundation of his fortune, which was valued at approximately $200 million at the time of his death. “Yep, I like horses,” he once remarked, “but I like people more.” And why not? As described by Art Jr., with the assistance of former Pittsburgh Press columnist Roy McHugh, the people with whom Rooney associated were exceptionally colorful and infinitely interesting.

Among the most memorable characters: his brother Dan, a.k.a. Father Silas, the two-fisted missionary who knew a thing or two about fervor; Uncle Jim, the hard-drinking mama’s boy who spoke in confidential asides and couldn’t sleep until he had given away all his money; Art’s bride, Kass, an elegant lady with a flair for the well-placed expletive; gluttonous Chris McCormick, who’d sooner miss a train than a steak; Radio Rich, an unofficial mascot who never removed the transistor from his ear; fan Joe Chiodo, who decorated his sports bar with brassieres and risked his life to defend Rooney’s good name; the “Paraclete of Kaborgia” a “prophet and messenger” sent by God to play for the Steelers; Coach Buddy Parker, obsessed with privacy and the number 13; Walt Kiesling, who had an unhappy talent for misjudging quarterbacks; and the idiosyncratic individuals who formed the famed Steel Curtain.

Readers familiar with Rob Zellers and Gene Collier’s 2003 play, “The Chief” (recently released in book format from the University of Pittsburgh Press), may recognize some of the material, but good stories bear repeating, and their repetition in no way diminishes the value of this book. “Ruanaidh” goes well beyond the scope of previous works on Rooney, providing the historical, cultural and familial context necessary to create a real 20th-century saga.

Ruanaidh (pronounced Ru-ah-nee) is the Gaelic version of Rooney, meaning “redhead.” It is an apt choice of title, evoking as it does the traditions of Irish legend that are very much part of the story. The 300-plus vignettes and character sketches assembled in “Ruanaidh” are presented in an informal, conversational manner resembling an oral history. They sometimes include a message or a moral, but are concerned primarily with conveying images of an enchanted past, unencumbered by historical research. (The author wisely issues a disclaimer early on, referring verification-seekers to the official biography of Art Rooney by Rob Ruck and Maggie Patterson that is due out next year). If a touch of blarney finds its way in, so much the better.

In some respects, “Ruanaidh” even recalls the Ulster Cycle mythology of Ireland’s Heroic Age—stories of a warrior society centered around the royal court at Emain Macha in the first century A.D. (Coincidentally, Emain Macha was established by Macha Mong Ruad, one of the greatest redheads in Irish history.) In this version, however, the king is of course Art Rooney, and his kingdom the North Side. His stronghold is the big house on North Lincoln Avenue, within sight of Three Rivers Stadium; the house, incidentally, in which Steelers chairman Dan Rooney now resides. The warrior society of ancient Ulster has its equivalent in both the boxing ring and the gridiron, where manly men do battle for honor and glory (and eventually, pretty hefty salaries) in Pittsburgh’s own working-class heroic age. And, as in any great legend, the actions of ancestors sow the seeds of contention for future generations.

Throughout his life, Art Rooney was accustomed to being the “alpha dog.” As the oldest of eight children, he felt responsible for his siblings and acted in a manner that often resembled noblesse oblige. Accordingly, his decision to name his own eldest son, Dan, heir to his position with the Steelers and its attendant prestige appears to have been less about favoritism than the age-old tradition of primogeniture. But just as Art’s good intentions incurred the resentment of some of his siblings and in-laws, Dan’s status and privilege apparently engendered some hostility among his brothers. All of Rooney’s boys were weaned on football; all revered their larger-than-life dad and sought his approval. It therefore seems likely that filial resentment—that age-old curse—plays a part in the current protracted dispute over the value and ownership of the brothers’ shares in the Steelers franchise, a full 20 years after their father’s death.

Unfortunately, Art Jr. makes no such statement in “Ruanaidh,” and actually divulges next to nothing about his brothers and their interrelationship. In a book that is built upon fantastic personalities, we learn very little about the characteristics of Art Rooney’s sons. Art Jr. shares some of his own feelings about his father, much about his personal experience with the Steelers, and a hint of the tremendous disappointment he felt when fired—by his brother—from his position as head scout for the team (in which capacity he was nominated to the Football Hall of Fame). But brothers Dan, Tim, Pat and John appear only tangentially. The current discord is never mentioned, except by the inclusion—as an appendix, and without preamble—of two documents from Art Sr. The first is a 1974 Christmas card expressing pride in his son and exhorting him to maintain a close-knit family. The second is a 1987 letter concerning the fair distribution of stock in the football club. Armchair detectives will enjoy reading between the lines of this fine work to deduce for themselves the causes of the current strife and predict its outcome. The story of Art Rooney may have ended in 1988, but the saga of his clan continues.