After Years of Torment in Venezuela, Novelist Finds Refuge in Pittsburgh’s City of Asylum

Israel Centeno is haunted by nightmares of his final years in Venezuela, waking in a lurch of panic as he relives the torment he long endured.

The burn of a cigarette jammed against his neck. A baseball bat smashing his car. The beating that broke his fingers. Once he was stabbed with a knife as he was leaving his apartment. Twice he was thrown in detention for seven days in isolation.

It went on for eight years as Centeno was repeatedly harassed, stopped while driving his car and told, at times in explicit detail, of plans to murder him.

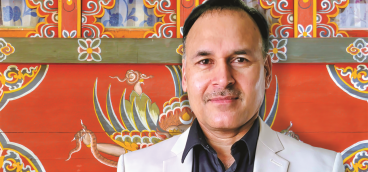

Before the attacks started, Centeno, 67, was a highly regarded novelist and a teacher who cherished his university position.

Things changed abruptly in 2002 after he published Conspiracy, a novel about a plot to kill the president of Venezuela. It was fiction, Centeno says, the 15th book he had published. But it made him a target, one of thousands routinely persecuted by government forces.

And it wasn’t just he who was targeted. His mother was publicly assaulted in Caracas by a man who threatened her and her son with murder. In one day, his mom said she received dozens of phone calls describing ways they intended to kill her son. Calls were made to his daughters’ school as well. “Constant surveillance,” says Centeno today. “They made sure I knew what they knew.”

In a journal, Centeno wrote of one frightening incident:

And then there was that night in the cistern truck. They left me there, in the middle of nowhere, under a sky so vast it felt mocking. The metal walls echoed with every blow, turning the truck into a drum. My head throbbed, and the sound filled my body, almost drowning my thoughts.

I remember the stars reappearing, faint but present, as they burned my neck, my stomach, my armpits. I recall the suffocation as they forced a plastic bag over my face, the moment I thought I’d never see my daughters again, never kiss my wife again, never smell the warm bread from Joao’s bakery.

During those hours, I prayed the rosary. I lost track of time—whether minutes or days passed didn’t matter. I clung to God, searching for meaning in the pain.

The threats and attacks on Centeno started under President Hugo Chavez, whose rule from 1999 until his death in 2013 led to the downfall of democracy in Venezuela.

Fifteen years after he left Venezuela, it remains acutely painful for Centeno to talk about the many incidents. He points to a burn scar on his neck as he continues in a halting manner, an eloquent writer with command of two languages, at a loss for words.

“They beat me and they beat my car with a bat. They broke my fingers, so I can’t write with my right hand. I had to leave and get my family out of there.”

In 2009, he went to Barcelona for a writers’ conference where he saw his publisher, who urged him to keep a diary of the incidents, and a friend who was a former writer-in-residence in Pittsburgh. That friend connected him with Henry Reese, who founded the Pittsburgh chapter of the City of Asylum along with Diane Samuel. The mission is to help persecuted and exiled writers “build a new home and a new life as part of a community.” The organization now includes Alphabet City, a literary center for readings and performances, along with a restaurant and a renowned bookstore.

The unjust treatment of targeted Venezuelan citizens under Hugo Chavez was well known at that time and continues today under the autocratic rule of President Nicolas Maduro, Chavez’s vice president. The slide from democracy to autocracy was slow but systematic as the party destroyed democratic institutions, charted a new constitution that gave the president more power, and shut down independent media. Increasingly, dissenters were punished.

Before his trip to Spain, Centeno had applied for a visa. Once he secured it, he fled his home country in 2010. He arrived in Pittsburgh as a writer-in-residence at City of Asylum, where he spent the next three years living and working in peace. His wife and two daughters were able to join him within 18 months.

The organization was a life preserver, he says. And while he lost his publisher in Venezuela and all rights to his royalties, City of Asylum shipped his library of 5,000 books to his new home, which was of immense comfort.

In Pittsburgh, Centeno continued his writing as he explored the city by bike, enrolled in English classes at Literacy Pittsburgh (then called the Greater Pittsburgh Literacy Council), and after his residency, got a job helping to discharge patients at Allegheny General Hospital. He also worked as a medical interpreter. He met a lot of good people along the way, he says, as he created a new life far removed from the traumatic one in Venezuela.

“By God’s grace, all of that is now part of my past,” he says. “However, healing has been difficult. In my faith, forgiveness is fundamental, but I cannot forget — not for myself, but for the victims who continue to suffer. Bearing witness, if only to disrupt the official narrative, is, in our case, justice and hope.”

More than 770,000 people have fled Venezuela since June of 2024 because of political unrest and hyperinflation (the highest in the world under Maduro) that led to dire economic conditions, ranging from acute shortages of food, medicine and electricity, to spikes in crime, disease and death rates.

Today the political landscape in Venezuela is worse than when Centeno left, the collapse of democracy complete. Compounding matters, in early February 2025, President Donald Trump rescinded the Temporary Protection Status of 600,000 Venezuelans residing in the United States.

“My family has attained citizenship, but it is a tragedy for the 600,000 Venezuelans who have nowhere to return,” says Centeno.

“It is unjust to paint an entire population with the actions of a criminal minority,” he wrote in a recent post, referring to El Tren de Aragua, the notorious crime group he says has links to those in power in Venezuela.

“The Venezuelan people are victims of a dictatorial regime and a failed economic model, not perpetrators of crime.”

Had he not fled, he says quietly and matter-of-factly, “I am certain I would have died. So many people I know disappeared after I left, never to be heard from again.”

Centeno remained in Pittsburgh for several years after his residency before moving briefly to Houston. It felt like a safe bet, going to a bigger city with a much larger Spanish-speaking population. But he missed the sense of security he felt in Pittsburgh, so he returned with his family.

“After Houston it felt like coming back home again,” he says. “It’s weird,” he admits, “because of my strong accent, you think it would be easier in New York or Houston where everyone is used to Spanish.”

Today he is an AmeriCorps member helping people find jobs at Literacy Pittsburgh and he continues as a freelance interpreter at FEMA.

He recently self-published three short books and wants to write two or three more. He is heartened to know that his earlier books written in Venezuela are still being sold today. “I’m glad people are still reading my books, even though I don’t get any kind of economic benefit,” he says.

He started a memoir with the hope that it would be therapeutic, but instead the process of reliving his tormented past has proved too difficult. “Too hard. The sense of loss. The pain,” he says, stopping in silence.

He has announced his intent to share half the profits from his new publications with Literacy Pittsburgh, a group that helped change his life.

“Pittsburgh, with its scars and possibilities, is my home now,” he wrote in a tribute. “Exile, like art, is rarely a choice. But if you’re fortunate, you find a place where roots can grow, even among the stones.”

It’s not easy being an immigrant, he reminds us. “We come here with difficulty. We are very vulnerable, and we have to handle a lot of prejudice.” He voices a common refrain, that an immigrant never feels like they truly belong.

His daughters are grown now; one is in national affairs, in the process of moving from Pittsburgh to Boston, and the other teaches Spanish locally.

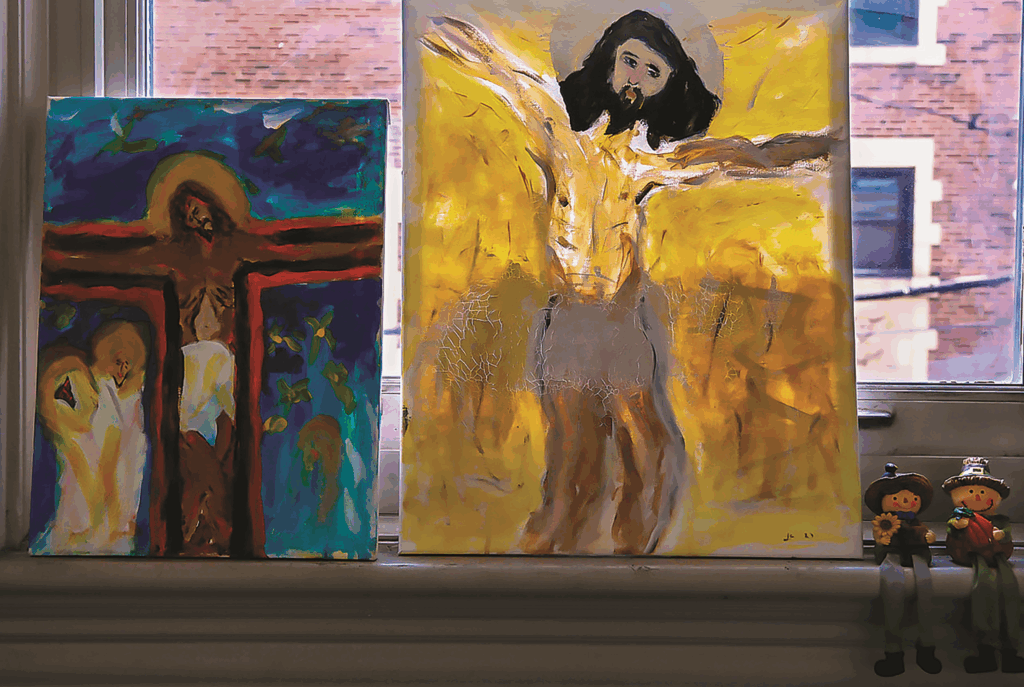

His wife, who suffered a massive brain hemorrhage years ago that robbed her of peripheral vision, tends to stay close to home in their cozy apartment with its shelves of books with Spanish titles and walls filled with colorful art. Most of it is religious in theme and painted by her husband.

“I don’t have any complaints about my life here. I am grateful,” says the writer. “I want to pay back, help people, help immigrants find jobs, help them learn English.”

As for Henry Reese and Diane Samuel, he cannot say enough. “Both of them mean the world to me. They are a blessing. I speak for all the writers who have been here at City of Asylum. They are like family.”